Homraj Acharya is an anthropology student in Dr. Adrienne Pine’s Craft of Anthropology I course (ANTH-601). This blog post was written in fulfillment of a course assignment. Images are published with permission from Mike Rechlin.

What would be the expression to describe a situation when the characters of your childhood stories spring to life and you get to actually meet them? I grew up hearing stories of “Mr. Mike” and “Mr. Dog,” who came from America.

Our elders said that if we dug a hole deep enough we would get to America. We tried, but the problem was, if you dug deep into the earth, the first thing that appeared would be water, and we thought we would drown in the well. So we gave up this idea of finding Americans in the underworld.

But some of them had lived in our village and planted trees, wore boots and brimmed hats, spoke English that sounded like popcorn, used their rare and valuable cameras (that no one in the village owned) to take photographs of mundane things like cows and water buffaloes, and loved the same food as those buffaloes. One of them had wiped his bottom with nettle leaves and then said that Nepal is so rich we have electric currents in our plants.

I grew up listening to the stories about Mr. Mike and Mr. Dog—two Americans who had lived in our village in the 1960s, just before I was born. They were both described to us kids as tall and thin with brown hat and boots. A riddle that I grew up hearing poked gentle fun at their appearance: “It is from America, is like a stick, and wears a hat. What is it?” (In Nepali, अमेरिकाने देशको, टोपी लाउँछ छेस्को, के हो”) The answer was a matchstick. We were solving that riddle in the 1970s and 1980s.

On September 18, 2019 I came across one of the real-life characters of the riddle in “Memories and Meaning: A 50th Anniversary Report,” catalogued in the American University Archives.

As part of Anthropology graduate classwork, our professor, Dr. Adrienne Pine, had scheduled a tour of the archives. I asked the archivist if they had anything on Peace Corps Volunteers (PCVs) working in Nepal.

I was curious to see how Peace Corps volunteers write privately about their experiences. I wasn’t expecting to find my own village in the archives. But in the list of sites I found the name of my village in connection to PCV Mike Rechlin.

Mr. Mike turned out to be Mike Rechlin, who was in our village as part of “Group 17” Peace Corps volunteers in 1969. Mike had spelled out the name of my village alongside the District. Certain it was the same Mike, I asked Leslie Nellis, Associate Archivist for Digital Initiatives and Record Management at the American University Library, to help me get connected with Mike and the other PCV if they were alive and around. I had assumed they would be in their 80s, as is my father, who worked along with them.

Mr. Mike and Mr. Dog figured in my childhood stories as the Gora Sahibs (White Sahibs). This a colonial-era term used to describe white British colonial masters in India, but it continued to apply to white people after the formal end of colonization.

One of the stories was about my father, one of the Gora Sahibs, and pumpkin daal (Kabaliko Daal). Daal is our daily food, a legume sauce served over rice. It can be made from chickpeas, lentils, split peas, or other legumes. Supposedly my father cooked for them one day and he had no legumes around so he used pumpkin, which he also used when he cooked for our buffaloes, who ate large amounts of vegetables and preferred their pumpkin cooked.

For the Gora Sahib, he apparently put sugar in the daal, which is not how daal is actually made. But he liked to put sugar in everything. Later, when my dad had to cook during when my mother had her menstrual cycle (when women cannot cook or do housework), he made us “the American Daal.” We did not like it. It was not fully cooked, and it had sugar in it. Who would want to have sugary daal? So, we don’t know which one of these two guys were responsible for changing our household recipes, but for four days a month we were forced to endure the sugary daal recipe.

Leslie connected me to Mike within a few days. I talked to him and it turned out he lives in West Virginia, only about three hours from Washington, DC, near a place where I have gone camping. We met and he shared some of the amazing photos, included below, from the late 60s

A few weeks later, I talked to my dad on a cell phone, which in itself is amazing. When I was growing up, I never even saw a telephone until I was 15, and at first, I spoke into the wrong end. But now we can call from America to fields in Nepal. I told my father that I met Mr. Mike and had dinner with him. He was thrilled to hear it. He extended his regards and namaste to Mike. There are very few people in the village who are still alive who would remember Mike and the other PCV in person.

Here are a few pictures of my village I received from Mike:

I recognize that this is my neighbor Maila Kumal on the left (still alive but old) and his father (now dead). This was pretty much how we dressed in the summer and how I grew up. They are of the pottery making Kumal caste. They still make this pottery. Here they are clearly posing for the camera with their freshly made water pots. We stored our drinking water in these pots. As it is very hot in the Terai region of Nepal in the summer, we would dig a pit in the ground of our kitchen to keep the pots cool. We lived in a thatched house like everyone else and our kitchen was an outbuilding with a thatched roof and mud walls, so the floor was also of dirt. Sometimes these clay pots are used for storing grains.

This brings back my own memories of plowing our land and leveling the field. In the picture above the land, according to Mike, is being leveled to prepare for planting trees like teaks and eucalyptus—part of the Australian forestry project that Mike was connected to. Leveling is fun for a kid because you get to ride on the leveler, which is that flat piece of wood behind the oxen. Sometimes a kid can sit between the legs of the plowing man just to have fun. We did that all the time. The boundary of work and play seldom exists. Work for adults can be part of the play for the kids. In fact, it helps the adults to have a little heavier pressure on the leveler and sometimes they would even call for kids to come and ride. This guy, who is now old, lives a couple hundred meters from our house. The place is called Sano Deuri.

I recognize that this is Nandu Tharu, and he seems to be bringing a grain storage container (deheri) that his wife made to one of the neighbor’s houses. This is how we transported things. This lariya (ox cart) was a multi-purpose vehicle for transporting sand from the rivers, harvested rice from the field, taking oilseeds to the oilseed press, bringing hay and logs from the jungle, and bringing brides after the wedding. Lariya are not as ubiquitous now because mostly they are replaced by tractors, but they are still around. These clay deheri in the cart are built in several segments of clay, rice husk, straw and cow dung so that different pieces can be assembled inside the home after they are complete.

This is a common community well for drinking water. The well is still there and the house in the background belongs to a family that weaves excellent baskets. I have some of their baskets in my house in Silver Spring. These women are using the same type of water pot from our earlier photo of the potters. In the background can be seen deheri (large storage pots) like the one being brought on the lariya, but they are decommissioned or they wouldn’t be outside. It seems they are being used just for firewood storage.

There is an inscription on the side of the well that has the sign of Om and then says 2022 Sukhadram. So the well was renovated 54 years ago (in 2022 BS / 1965 CE) and the renovation must have been sponsored by Sukhadram. It is interesting that somebody made the om sign left side right. It should be facing the other way. These women are Tharu, from the community indigenous to the area, and are wearing beautiful traditional dresses, which are now uncommon as the women in the village mostly wear Bollywood style saris and blouses today. Their armlets are made of pure silver and also have mostly gone out of usage.

These Tharu women are fishing in the local ponds with their hiluka (small nets with rounded frames) and ghanghi (large nets with more triangular shapes), and deli (or perungo) on the west to catch minnows. This is a community fishing event. People are not allowed to fish in these community ponds as and when they please; there is a particular day as decided by village Badhghar (a village chief, elder) that the members of the community (usually women from village) can go and fish, so that everyone has an equal opportunity to catch fish. Sometimes they will catch fish and then collect and divide.

This is a major lake of our village. It is known as Buddhi Lake. Tharu women are fishing with hiluka nets. The official area of the two lakes combined now is 47 acres. When Mike was in Buddhi, these lakes were divided into two lakes, one for the community and one for generating revenue for the village council. In recent years, both lakes have been combined and redesigned and contracted out for 5 to 10 years to the highest bidder. Last cycle the winning bid was for 4.2 million Rupees—equivalent to $40,000 USD.

These women are husking rice in a dhiki, a large wooden beam that is pumped by foot and drops onto the rice, separating the husk and kernel of the rice. That was one of the tasks I had to do regularly as a child. I would come home from school and have to husk the rice with the dhiki and feed the husks mixed with pumpkin to the buffaloes and cows. We used to be in a hurry to do something else, like go out and play, so the idea was to finish as quickly as possible and pump it really fast. But that actually breaks the rice into smaller pieces and you get yelled at.

I grew up in a similar house until about 7 years of age. Every year in the winter I had to go to the jungle to cut fresh thatch for the house and also for the kitchen and barn. Then we built a house made of mud bricks that we made by hand, though even today a portion of the cowshed is thatch. Many of these houses have changed, with walling material mostly of bricks and roofs replaced by corrugated tin sheets or RCC (rod, concrete and cement) for those who can afford it.

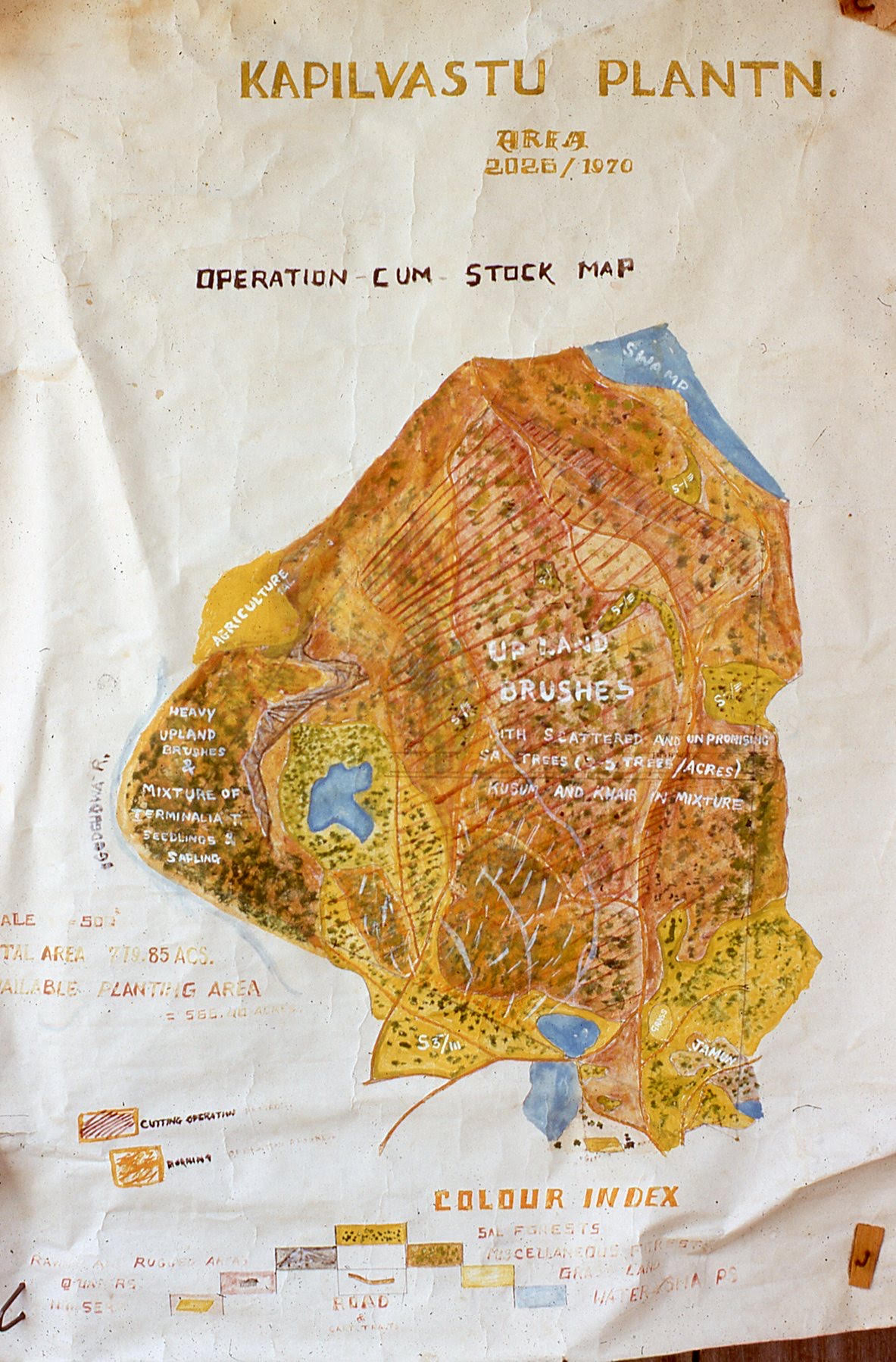

This is the map of the village showing how much was forested at the time. I had actually never seen a map of my village before seeing this one. The river on the far left is where I learned to swim. It is now often low or even fully dried so that you can cross the river without taking your shoes off. This is the result of a combination of climate change, deforestation and silting from erosion upstream.

On the bottom right is a jamun (black plum) grove where we used to go in July and August to pick them in the forest. Sadly, there has been much deforestation and the area identified with jamun isn’t there anymore as a forest. The sal trees were also essentially all felled during the political transition of the 1990s. Some of the teak and eucalyptus trees (Mike’s project) are still there but most have been cut down. The Kusum trees which are identified in the map have also been cut down, and the mango and Seemal trees are almost all gone now. I am curious why it says “unpromising Sal trees,” as I recall many Sal trees in this area highly valued as hardwood. There is a saying in the village that a Sal tree lasts for 3,000 years – standing for 1,000 years, on the ground for 1,000 years, and another 1,000 to completely decay.

AU’s Peace Corps Archive contains historical treasures that have serendipitously re-connected me in entirely new ways to my childhood stories, creating the potential for new, richer interpretations of my own village’s history. These new interpretations will help us better understand the processes that have led us to where we are today, and will also provide insights into the broader, long-term impacts of the Peace Corps in societies like my own.