In theory, Project Peace Pipe intended to attract Native American applicants, diversify Peace Corps volunteers, and build the skills and confidence Indigenous trainees needed to serve two years in Colombia. However, in practice, twenty-nine volunteers arrived for training, five received placements, and only two completed full service. In the final project evaluation report, surveyors attributed the program’s failure to “racism…bungling…bureaucratic deafness [and] …sheer ignorance” of program administrators, leading training officials to wonder if Project Peace Pipe was doomed from the start.[1]

Recruitment

During the 1960s, Peace Corps recruitment featured advertisements stressing adventure, personal growth, and building international relationships—things that appealed to many Americans, but failed to consider other barriers to entry. As mentioned in “Project Peace Pipe”: Developing the Program, the project was one of the first attempts by the Peace Corps to specifically draw individuals from disenfranchised groups. Officials determined that a targeted enrollment campaign and adjusted application requirements would help these efforts.

Looking at retention rates from earlier groups, Peace Corps officials found that volunteers aged 20 or older were more likely to complete service than their younger counterparts. Therefore, recruiters for Project Peace Pipe focused on older volunteers—making the average age of trainees around 23 years old. They also voted to give personal interviews more weight than written references, as previous statistics reported that lower socio-economic class applicants had more difficulty obtaining written references.[2]

| Application Requirements |

| Project Peace Pipe |

Peace Corps |

| At least 20 years old |

At least 18 years old |

| High school diploma; some college |

High school diploma; some college; bachelor’s degree |

| Personal interviews |

Written references |

Recruiting efforts focused primarily on colleges with a high population of Native students, Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) schools, and areas with large American Indian populations. The BIA funded a grant for new brochures and hired BIA education officials to identify possible candidates. Yes, the federal agency that sponsored boarding schools for Indigenous children under the motto, “Kill the Indian…save the Man,” also supported efforts to train American Indian Peace Corps volunteers. [3]

Donald Broadwell recalls the recruitment process in a 1998 letter to Friends of Colombia President Robert Colombo:

I was atypical of the Project Peace Pipe volunteers, having had little real identification with Native American culture prior to my entry into the Project…Although I grew up in Mahnomen County, Minnesota, which is part of the White Earth Reservation, it is an “Open Reservation,” i.e., one which transferred the property to individual tribal members…The Project Peace Pipe recruiters took the attitude of “close enough!” and signed me up.

The other 29 applicants came from clusters of the West around South Dakota, New Mexico, Minnesota, and Arizona—with varying levels of involvement with their Indigenous culture. Despite the initial prerequisite to recruit volunteers over twenty, six were between eighteen and nineteen years old, although the rest ranged in age between twenty and twenty-nine.

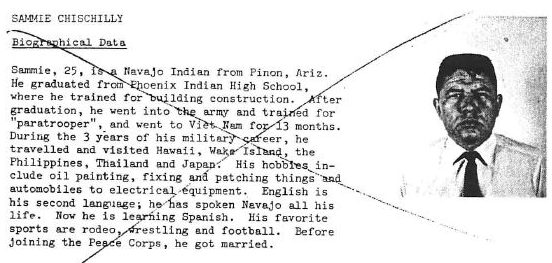

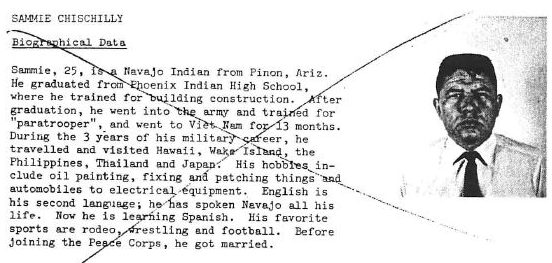

Sammie Chischilly served three years in the army as a paratrooper in Vietnam prior to joining the Peace Corps. He and his wife Cynthia left training while in California. Sammie Chischilly, Peace Corps Escondido, Summer 1968. Colombia Rural Community Development Group B, August 28-October 14, 1968.

Training Programs

Project Peace Pipe applicants joined “Colombia- Rural Community Development- Group B,” (RCD-B) however, the Project Peace Pipe program was a sub-category within this larger Peace Corps group. These volunteers attended six extra weeks of training in Arecibo, Puerto Rico before joining volunteers from the general group. The pre-training operated under the assumption that “lack of confidence was a major barrier for Indians interested in Peace Corps Service,” and so the program was devoted more towards developing Native “self-awareness” and skills for service overseas.[4]

To do so, OIO (Oklahomans for Indian Opportunity) inverted the Peace Corps’ cross-cultural training model by designing a pre-training that sought to reverse “psychological effects of internal colonization, [and instead] emphasize the racialized and economic inequalities within the United States rather than impending culture shock abroad.”[5] Like the typical Peace Corps training, Peace Pipe trainees received intense Spanish language training; however, in place of Colombian history and practical skills training, they received “communication” and “attitudinal” training directly focused on changing the temperaments of Peace Pipe volunteers. One component consisted of a week “imaginal education” course and discussion groups three times a week for self-confidence counseling.[6]

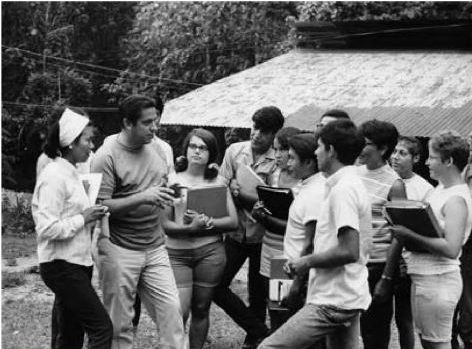

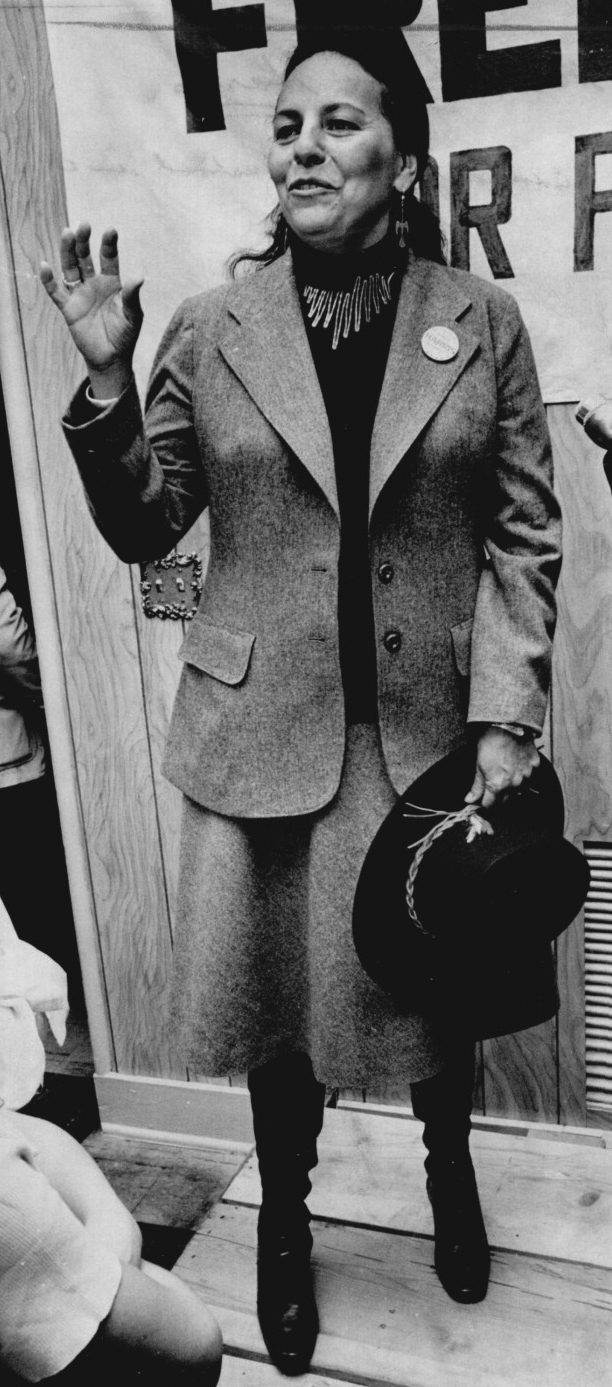

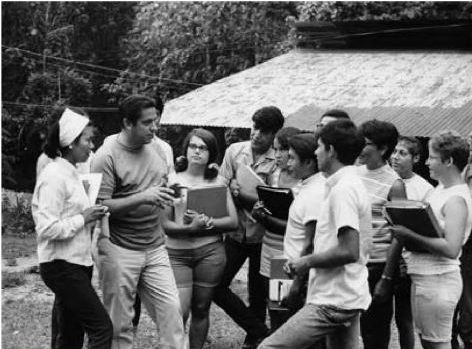

Project Peace Pipe recruits speaking with Senator Fred Harris during training in Puerto Rico, 1967. Featured in Alyosha Goldstein, Poverty in Common: The Politics of Community Action during the American Century, Duke University Press, 2012. Courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, D.C. (490-G-63-82068-C2-19)

The Project Peace Pipe pre-training seemed to be a success, with close relationships formed between the trainees and staff, and most of the volunteers transitioning into the general Peace Corps training. However, Donald Broadwell describes the altered atmosphere following the arrival of other Peace Corps volunteers:

Most of the Project Peace Pipe volunteers were, like me, young and without college educations. Most of us had had some college experience, but most had not completed a degree. We were a group who were interested in an adventure, but most of us did not have the inner resources to be fully independent. We enjoyed our Pre-training experience in Puerto Rico, where we received intensive training in Spanish and a little bit of training in establishing cooperatives.

Many of us found the transition to the training program in California to be a difficult one to make, and many volunteers began opting out of the program. Other volunteers joining us for RCD-B were largely college educated and a few years older than the Project Peace Pipe volunteers. Many of us felt we couldn’t “measure up” to the other volunteers joining us, and began to feel overwhelmed with the prospect of being independent in a foreign country, whose language we spoke only haltingly.

The issue of retaining Peace Pipe trainees continued throughout training and service. An article by LaDonna Harris and Dr. Leon H. Ginsberg, social work professor at the University of Oklahoma, Norman, reported: “In addition to the pressure of selection for Peace Corps service…, the composition of the training group itself was perceived as potentially threatening for some American Indian trainees.”[7] Whereas the middle-class Ivy League and large state university volunteers experienced culture shock overseas, the psychologists within the RCD-B training reported adjustment issues with Native volunteers once merged with the predominantly white trainees.

The language used by Broadwell, Harris and Ginsberg attribute this issue to intimidation from the superior experiences of other volunteers; however, a survey of the group’s biographical pamphlet reveals something else. While the project evaluators described Peace Pipe volunteers as lacking confidence and skills in communication, the pamphlet reported that most had attended some higher education schooling, spoke two or more languages fluently, and already performed leadership roles within their local communities. Several had traveled around Mexico, Canada, and Puerto Rico, and one woman served as a Congressional intern on Capitol Hill.[8] While many may have felt that they didn’t “measure up” as Broadwell suggests, others felt suffocated by rigid expectations. One unidentified Peace Pipe trainee complained in an interview with the Washington Post, “Peace Pipe seems like an effort to make us nice little WASPS so that we can fit in…”[9] Ironically, the fears that Peace Corps officials had regarding the agency’s “lily-white” composition destroyed their intentions to appeal to minority group volunteers.

The Results

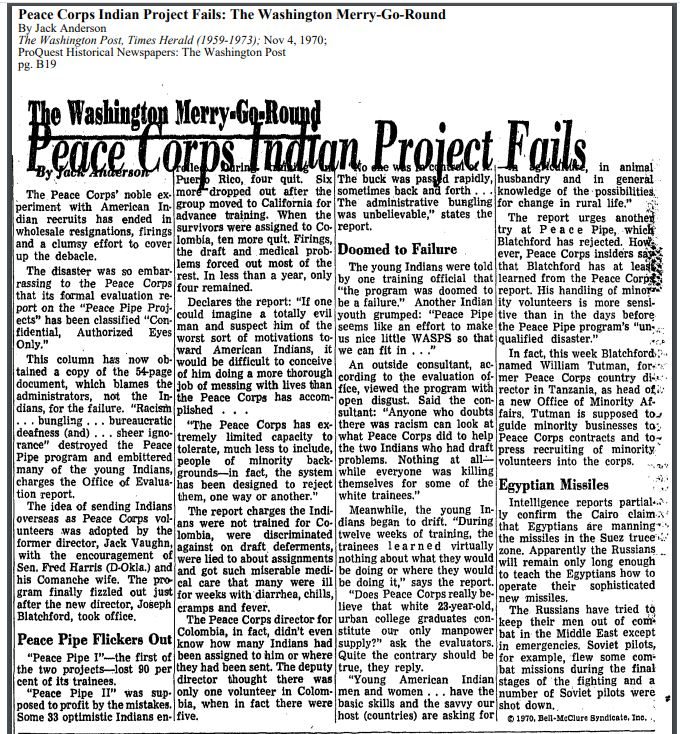

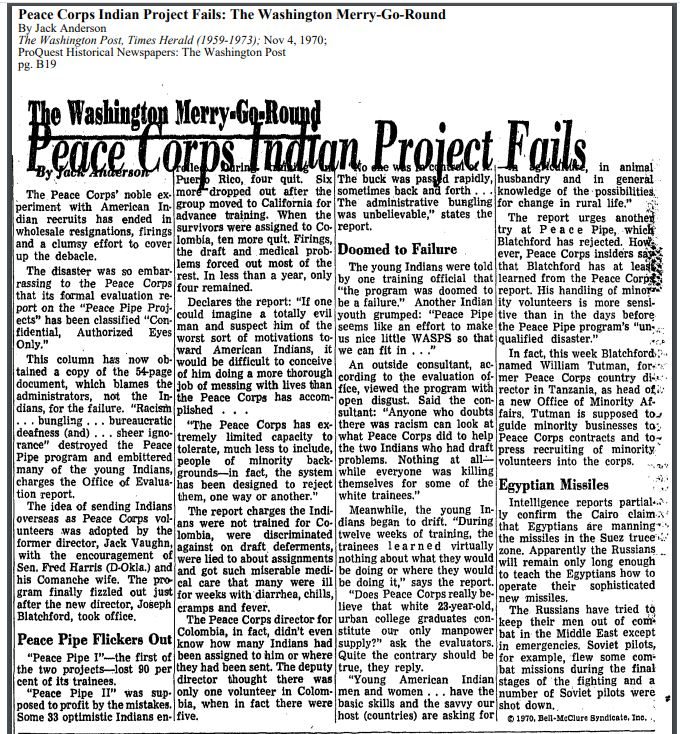

Project Peace Pipe ran for three years—just long enough to train and place 2 groups of volunteers—before termination. By 1970, only six trainees from Project Peace Pipe served full terms in Colombia. The Washington Post, who wrote about the results in November 1970, reported that undercurrents of racism marked the program and the instructors believed the program was doomed to fail:

The report charges the Indians were not trained for Colombia, were discriminated against on draft deferments, were lied to about assignments, and got such miserable medical care that many were ill for weeks…

…An outside consultant, according to the evaluation office, viewed the program with open disgust. Said the consultant, “Anyone who doubts there was racism can look at what Peace Corps did to help the two Indians who had draft problems. Nothing at all—while everyone was killing themselves for some of the white trainees.” [10]

Jack Anderson, “Peace Corps Indiana Project Fails,” Washington Post, 4 November 1970.

The article also indicated that the failure resulted in the creation of the Peace Corps’ first Office of Minority Affairs, as part of the agency’s “New Directions” initiative. Peace Corps Director Joseph H. Blatchford appointed the former director in Tanzania and Black American, William Tutman, as the office’s new head.[11] Tutman resigned the following April, writing that “while dedicated to cross-cultural understanding abroad, [the Peace Corps] has failed to deal with the subcultural misunderstanding in its midst.”[12] An article in the New York Times reported that Tutman pointed to specific examples of discriminatory hiring practices and preference given to “white males.” The article also cited Blatchford’s statement regarding the resignation, asserting, “the record of the Peace Corps in minority affairs has been outstanding,” and promised to name a “prominent black American” to fill the post.

The Peace Corps’ reputation regarding racial and cultural sensitivity has improved since the ’70s. Today, volunteers from a variety of backgrounds share how their identities impact their service on the official Peace Corps blog. Here, you can read reflections by several Indigenous volunteers serving in the 2010s—Madiera Dennison, Anthony Trujillo, and Dennis Felipe Jr.

References:

Peace Corps Honors American Indian Volunteers, October 31, 2008.

Peace Corps Celebrates National Native American Heritage Month, November 5, 2009.

Peace Corps Escondido, Summer 1968. Colombia Rural Community Development Group B, August 28-October 14, 1968.

Sterling Fluharty, “Harris, LaDonna Vita Tabbytite,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=HA035.

Fritz Fischer, Making Them Like Us: Peace Corps Volunteers in the 1960s (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998), 102 –3.

[1] Jack Anderson, “Peace Corps Indian Project Fails,” Washington Post, November 4, 1970, B19. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[2] Harris, Mrs. Fred R. and Leon H. Ginsberg, “Project Peace Pipe: Indian Youth Pre-Trained for Peace Corps Duty”, Journal of American Indian Education, Vol. 7 No. 2, January 1968, 23.

[3] Charla Bear, “American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many,” NPR, May 12, 2008. npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=16516865

[4] Harris, Mrs. Fred R. and Leon H. Ginsberg, “Project Peace Pipe: Indian Youth Pre-Trained for Peace Corps Duty”, Journal of American Indian Education, Vol. 7 No. 2, January 1968, 23.

[5] Alyosha Goldstein, Poverty in Common: The Politics of Community Action during the American Century, Duke University Press, 2012, 104.

[6] Harris, Mrs. Fred R. and Leon H. Ginsberg, “Project Peace Pipe: Indian Youth Pre-Trained for Peace Corps Duty”, Journal of American Indian Education, Vol. 7 No. 2, January 1968, 25.

[7] Harris, Mrs. Fred R. and Leon H. Ginsberg, “Project Peace Pipe: Indian Youth Pre-Trained for Peace Corps Duty”, Journal of American Indian Education, Vol. 7 No. 2, January 1968, 23.

[8] Peace Corps Escondido, Summer 1968. Colombia Rural Community Development Group B, August 28-October 14, 1968.

[9] Jack Anderson, “Peace Corps Indian Project Fails,” Washington Post, November 4, 1970, B19. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[10] Jack Anderson, “Peace Corps Indian Project Fails,” Washington Post, November 4, 1970, B19. ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

[11] “Director Blatchford Names New Peace Corps Program For Minorities and Women,” The Harvard Crimson, November 7, 1970. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1970/11/7/director-blatchford-names-new-peace-corps/

Joseph H. Blatchford, “The Peace Corps: Making it in the Seventies “Foreign Affairs, October 1, 1970. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/1970-10-01/peace-corps-making-it-seventies

[12] “Peace Corps Aide Quits In Protest,” The New York Times, April 19, 1971. Page 41. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/04/19/archives/peage-corps-aide-quits-in-protest-minority-affairs-director-charges.html