The Postcard Incident

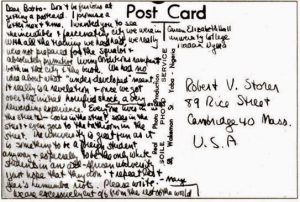

Marjorie Michelmore was a 23-year-old Smith College graduate when she applied to the Peace Corps in 1961. Selected to serve as an English teacher in Nigeria, Marjorie became a member of the first cohort of Peace Corps Volunteers (PCVs) sent to the country. After two months of teacher training at Harvard University, the volunteers flew to Nigeria to complete phase two of training at University College in Ibadan. On October 13, 1961, Marjorie Michelmore wrote a postcard to her boyfriend back in Boston. She drew a scene of the city of Ibadan on the front of the postcard and wrote on the back:

“Dear Bobbo: Don’t be furious at getting a postcard. I promise a letter next time. I wanted you to see the incredible and fascinating city we were in. With all the training we had, we really were not prepared for the squalor and absolutely primitive living conditions rampant both in the city and in the bush. We had no idea what “underdeveloped” meant. It really is a revelation and after we got over the initial horrified shock, a very rewarding experience. Everyone except us lives on the streets, cooks in the street, sells in the street, and even goes to the bathroom in the street. Please write.

Marge

P.S. We are excessively cut off from the rest of the world” [1].

The postcard, however, was never mailed. In a 2011 interview for the Smith Alumnae Quarterly, Smith College’s alumnae magazine, Margery recalled: “I either dropped the postcard or it was taken out of the mailbox. I have no idea how it was found” [2]. Either way, a Nigerian student found and made copies of the postcard and distributed them throughout the university. The students were furious. They attended rallies and passed resolutions that denounced PCVs as “America’s international spies” and their teaching program as “a scheme designed to foster neo-colonialism” [3]. The story appeared in nearly every Nigerian and U.S. newspaper. While the “Peace Corps Postcard” incident is a well-known story, it is also telling of the agency’s flaws. Marjorie Michelmore’s story sheds light on the most prevalent critiques of the early Peace Corps and allows us to consider the agency’s role in both the past and the present.

“Kennedy’s Kids” & Naiveté

Marjorie Michelmore represents the ideal PCV in the agency’s early years—a young, recent college graduate. At the heart of the Peace Corps mission was the idea that America’s young people were motivated and enthusiastic global citizens with a deep commitment to humanitarian service. The notion of sending young, unskilled college graduates abroad to fix the world’s problems, however, received ample criticism. President Dwight D. Eisenhower referred to the Peace Corps as a “juvenile experiment” [4]. The nick-name assigned to the first wave of volunteers, dubbed “Kennedy’s Kids,” reflects public perceptions of amateurism. This critique certainly holds some truth. In the 2019 documentary A Towering Task: The Story of the Peace Corps, Christopher Dodd —Returned Peace Corps Volunteer (RPCV) and former U.S. Senator from Connecticut—says:

“The idea that I—an English Literature major—it was a presumptuous idea that I was somehow going to eradicate ignorance, poverty, and disease.”

Christopher Dodd (RPCV: Dominican Republic, 1966-1968)

A Towering Task: The Story of the Peace Corps (2019)

Dodd’s reflection puts words to the ultimate paradox of the Peace Corps. Although thousands of young Americans were inspired by President Kennedy’s call to action, PCVs often found that their efforts were not enough to make a large-scale impact. While naiveté is a prominent critique of the Peace Corps, the same concept—that young Americans could go abroad and fix complex global problems—brings forth questions of neo-colonialism.

Decolonization & Neo-Colonialism

The Peace Corps emerged during the post-war era of decolonization. After World War II, dozens of countries in Africa and Asia gained independence from European empires. In the 1950s and 1960s, international development volunteering organizations emerged across the globe—Australia’s Volunteer Graduate Scheme (VGS) in 1951, Britain’s Volunteer Service Overseas (VSO) in 1958, and the United States’ Peace Corps in 1961, to name a few. Development volunteering models, including the Peace Corps, exacerbated a neo-colonialist distinction between “developed” and “developing” nations [5]. In the case of Marjorie Michelmore, Nigerian students condemned the Peace Corps’ teaching program as a “scheme to foster neo-colonialism.” Nigeria had been independent for just one year at the time of the postcard incident. Many newly independent nations were reluctant to allow PCVs into their country to begin with. Margery’s discussion of “primitive” conditions and her blatant use of the word “underdeveloped” not only broke the trust of host country nationals, but also echoed the colonial rule that the country had just broken free from.

Cold War Competition & Suspicion

After seeing the ways in which Marjorie Michelmore described their country, Nigerian students suspected PCVs were “international spies.” This allegation reveals another dimension of Peace Corps critique. The Peace Corps was, in many ways, a response to the Cold War—an era of heightened international tension, suspicion, and fear. Founded at the height of the Cold War, motivations for the establishment of the Peace Corps certainly venture outside of promoting “peace and friendship” abroad. Was the goal of the agency to foster peaceful international relations? Was it to assist in the development of emerging nations? Was it to show the Soviet Union and the world the power of American democracy and capitalism? Or, was it to “win” the allegiance of unaffiliated countries? With historical hindsight, we can infer that it was all of the above.

The founders of the Peace Corps were keenly aware of the pervasiveness of Cold War ideology, however. President Kennedy, Sargent Shriver, and others worked hard to allay fears that the Peace Corps would harbor secret agendas or become a tool of the CIA by requiring countries to request volunteers. To this day, previous work with an intelligence agency automatically disqualifies citizens from Peace Corps service. Despite these measures, host countries were still suspicious of the Peace Corps. Concerning Marjorie Michelmore, Nigerian students almost immediately questioned the motives of American volunteers. While the founding of the Peace Corps in 1961 cannot be divorced from the political climate in which it emerged, it is also difficult to overstate the significance of the establishment of the Peace Corps, an agency devoted to peaceful engagement with the world, amidst Cold War international tensions.

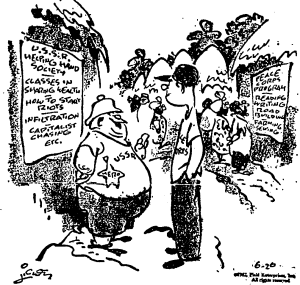

During his presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy said in regards to the establishment of a peace corps: “I want to demonstrate to Mr. Khrushchev and others that a new generation of Americans has taken over this country…young Americans [who will] serve the cause of freedom as servants of peace around the world, working for freedom as the communists work for their system” [6]. This quote and the above cartoon, published in the Washington Post on June 26, 1962, demonstrate the influence of the Cold War on the establishment of the Peace Corps. Not only did the United States want to compete with the Soviet Union for the allegiance of newly independent nations, they also wanted to promote American democracy abroad.

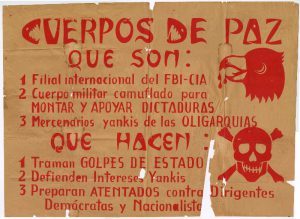

Poster denouncing the Peace Corps in Colombia. Translation: “The Peace Corps is: 1) an international affiliate of the FBI-CIA, 2) a military corps that supports dictatorships, and 3) yankee mercenaries of the oligarchies. What do they do: 1) plot coups, 2) defend yankee interests, and 3) prepare attacks against democratic and nationalist leaders.”

The Peace Corps has remained a controversial agency throughout its history. I address additional questions and critiques briefly below.

The Peace Corps vs. the War Corps

Early proponents called for the implementation of a program like the Peace Corps to provide a “moral equivalent to war” [7]. Richard Nixon, however, famously deemed the Peace Corps a “haven for draft dodgers.” In 1966, as war raged in Vietnam, over 15,000 PCVs were promoting peace and friendship abroad. There is no greater demonstration of the tension between the altruistic idealism and the harsh political realities that defined the sixties in America [8]. More firmly, the Peace Corps is a crystallization of American attempts to engage with the world in a different, more peaceful way. Considering the Peace Corps in tandem with the U.S. military also poses evocative questions. Is service in the name of peace just as worthy of respect and remembrance as that of war?

Is the Peace Corps an apolitical agency?

The Peace Corps was established as an independent agency within the State Department to avert influence from short-term foreign policy goals. Throughout its history, however, the Peace Corps has struggled to navigate the dynamics between the White House, policymakers in Washington, DC, Peace Corps leadership, and volunteers abroad. To date, the agency has operated under 12 U.S. presidents and 20 Peace Corps directors. The Peace Corps has, at times, strayed from its mission and promoted the White House’s foreign policy goals to remain relevant. For example, when the Cold War ended, President George H.W. Bush eagerly sent Peace Corps Volunteers to Eastern Europe to “impart capitalism” [9].

Volunteer Safety

In 2009, Kate Puzey was serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the West African country of Benin. Puzey believed a Peace Corps employee was sexually harassing female students at the school where she taught and sent an email to her country’s headquarters to inform them. Although she asked to remain anonymous, Puzey was found dead shortly thereafter. President Barack Obama signed the Kate Puzey Peace Corps Protection Act in 2011, designed to protect Peace Corps Volunteers and improve the agency’s response to acts of violence and sexual assault [10]. Nevertheless, in 2021, many RPCVs came forward and expressed their disappointment in the Peace Corps after experiencing sexual assault during their time of service, and not receiving support from the organization [11]. Kate Puzey, however, is just one PCV who died during service. Engage with The Fallen Peace Corps Volunteers Memorial Project to learn about the more than 500 PCVs who died during service.

BIPOC & Queer Volunteers

Race, sexual orientation, and gender identity greatly influence Peace Corps experience. African American, Asian American, and Latino PCVs have been questioned if they are really Americans in their host countries. What does this say about perceptions of Americanism abroad? Identifying as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender is illegal in many countries. Queer volunteers often have to weigh coming out to their community with the potential danger that it may put them in. View Many Faces of Peace Corps, 60th Anniversary and explore the former LGBT Returned Peace Corps Volunteer Association website to learn more about how race and identity shape Peace Corps service.

Does the Peace Corps make any positive impact on host countries?

The everlasting question of impact has haunted the agency since its inception. Does Peace Corps service primarily benefit the volunteers? Volunteers have the opportunity to live abroad, add to their resume, and receive eligibility for government jobs upon their return. Many volunteers do report that they gain much more from the international communities they serve than they give. Historically, the Peace Corps has struggled to quantify its success because it is typically on an interpersonal level.

Is the Peace Corps still relevant today?

If the Peace Corps is a Cold War relic, is it still relevant? RPCV Lacy Feigh writes for the Washington Post’s Made By History:

“At 60 years old, has the Peace Corps outgrown its time and relevance? Viewed as an organization meant to provide foreign aid and development, maybe. But as a vehicle to build relationships, empathy, and experiences, it is as important as ever” [12].

Just as the Peace Corps faced challenges at home and abroad in the 1960s, the organization faces challenges today. In 2020, for the first time in its history, the Peace Corps evacuated all volunteers from their posts due to COVID-19. During that time, the agency reflected on how they can redefine their mission to remain relevant today. Read the 2020 National Peace Corps Association’s (NPCA) report, Peace Corps Connect to the Future, to learn about the future of the Peace Corps.

Abolish the Peace Corps?

While some view the mission of the Peace Corps as more important than ever, others are vying for its abolishment. Shortly after being evacuated from Mozambique due to COVID-19, 3 PRCVs founded Decolonizing Peace Corps—a project to abolish the Peace Corps. Functioning primarily through Instagram, Decolonizing Peace Corps collects data from volunteers and host country nationals with the hope of inspiring the abolishment of the Peace Corps by 2040 [13].

The Peace Corps has been a contentious agency since its inception in 1961. While it is difficult to disentangle the Peace Corps’ idealistic fervor from its shortcomings, understanding and recognizing criticism of the agency allows us to better understand its complex history and rethink the ways in which it can or should exist in society today.

References

[1] John Coyne, “Our Most Famous and Infamous RPCV: Marjorie Michelmore (Nigeria),” Peace Corps WorldWide, November 2, 2019.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Stanley Meisler, When the World Calls: The Inside Story of the Peace Corps and its First Fifty Years (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011), 39.

[4] Meisler, When the World Calls, 42.

[5] Agnieszka Sobocinska, “How to Win Friends and Influence Nations: The International History of Development Volunteering,” Journal of Global History, 50-51.

[6] Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1965), 606.

[7] “Peace Corps Fact Book, April 1961,” From Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. President’s Office Files. Departments and Agencies. Peace Corps, 1961: January-June. https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKPOF/085/JFKPOF-085-015.

[8] Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman, All You Need Is Love: The Peace Corps and the Spirit of the 1960s (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 10.

[9] Meisler, When the World Calls, x-xi

[10] Angela M. Hill and Randy Kreider, “Obama Signs Kate Puzey Volunteer Peace Corps Protection Act,” ABC News, November 21, 2011.

[11] Donovan Slack and Tricia L. Nadolny, “Sexual Assault rises as Peace Corps fails its Volunteers,” USA TODAY, April 22, 2021.

[12] Lacy Feigh, “Now 60 years old, the Peace Corps can be more than a Cold War artifact,” Made By History at the Washington Post, 5 March 2021.

[13] Shanna Loga, “Should the US Abolish the Peace Corps?,” Medium, September 20, 2020.