Happy Halloween! In honor of the upcoming holiday, today we present to you the story of a special Peace Corps-themed whodunnit. Author Rosemary Yaco served in the Peace Corps in Togo from 1983-1986. [1] She then served as a Fulbright professor in Togo before working as the Director of the English Language Program, which was at the United States Information Agency American Cultural Center in Benin, until 1996. [2] From 1998 to 2006, Yaco published a series of four murder mystery novels whose main character, Lynne Lewis, solved crimes in the West African settings where Yaco had worked. [3] The first book in this series, titled Murder in the Peace Corps, reflected Yaco’s service in Togo. It drew on a tragic event that happened during her time as a Volunteer, while also involving several twists, turns, and an enigmatic group of suspects.

Inspiration From Tragedy

(Content Warning: This section contains discussions of murder and police violence.)

Rosemary Yaco’s 1983 Peace Corps group included Jennifer Rubin, a young woman who started her own project to help Togolese women make more efficient earthen stoves, reducing the work needed to gather firewood for cooking. [4] In 1984, she realized that the daughter of the family she rented an apartment from, a close friend, was stealing her belongings. When Rubin mentioned this to the father, he turned his daughter into the police, who beat her until she confessed. A few days later, when she was released, she contacted two men from another village, who killed Rubin. [5] The two men who killed her were sentenced to life in prison. [6] This senseless death of a Peace Corps Volunteer clearly impacted Yaco, as can be seen in her book. Murder in the Peace Corps begins when Lynne Lewis hears word of a fictionalized account of this murder, and Lynne’s sadness and hope to find a resolution grounds the mystery in the shadow of Rubin’s death. [7]

Thickening the Plot

Just as in real life, the Peace Corps and Togolese government in Murder in the Peace Corps quickly resolve this first murder. However, when Lynne and the other Peace Corps Volunteers assemble to grieve and obtain more information about the murder, the Ambassador of the United States to Togo dramatically dies in front of them. Lynne quickly sets off on a cross-country adventure, involving both help and hindrance from the American Embassy, her fellow Volunteers and supervisors, and the local Togolese people. Rosemary Yaco weaves intrigue, romance and surprise into her plot, and the mystery is resolved through several unexpected twists. In addition, she includes details that clearly come from her own Peace Corps experience, such as the delicious food Lynne eats or the types of housing she lives in. However, not all of these specifics are delightful. Not unlike many other thrillers, the sexual orientation of multiple characters is used to signal “deviance” and suggest the characters have malicious or jealous motives because of their suppressed sexual orientation. Yaco’s Peace Corps Volunteers also sometimes get angry at the cultural differences between the United States and Togo, assuming theirs are always superior, or they exoticize the Togolese they come into contact with. Yaco also underscores the isolation and difficulty adjusting that can occur when Volunteers have isolated posts, or the irritation which comes when they don’t get along with each other. [8]

The Final Conclusion

Rosemary Yaco’s Murder in the Peace Corps is a mystery that uses more than just suspense to spin a tale. By incorporating real-life experiences, Yaco transports readers to Peace Corps service in 1980’s Togo, accompanied by a plucky heroine and an intriguing set of supporting characters. Interested readers can find the digitized book online in Yaco’s collection within the Peace Corps Community Archives, here.

Notes

[1] “September 1, 2001: Headlines: NPCA: Fortieth Anniversary: Custom Conference: Who signed up for the original Peace Corps 40th – sorted by Country of Service (Part 3),” Peace Corps Online, http://peacecorpsonline.org/messages/messages/2629/2023295.html. Accessed September 28, 2022.

[2] “Lynne Lewis: West Africa Murder Mysteries,” Sonia Yaco, https://soniayaco.com/lynne-lewis-west-africa-murder-mysteries/. Accessed September 28, 2022.

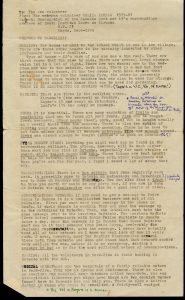

[3] Rosemary Yaco, Murder in the Peace Corps (Anlex Computer Consulting, 1998), 1, https://soniayaco.com/murder/peace_toc.htm; Rosemary Yaco, Murder at a Small Embassy: Evil in Benin (Anlex Computer Consulting, 2006), 6, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://soniayaco.com/murder/evil_embassy1.pdf.

[4] “Jennifer Rubin ’83 (Togo, 1983-84),” Hamilton Online Review, Fall 2007, in “Jennifer Rubin,” Fallen Peace Corps Volunteers Memorial Project, https://fpcv.org/volunteers/jennifer-rubin/, accessed September 28, 2022.

[5] “AN IDEALIST’S SHORT LIFE ENDS IN A KILLING IN A TOGO VILLAGE,” The New York Times, July 4, 1984, https://www.nytimes.com/1984/07/04/world/an-idealist-s-short-life-ends-in-a-killing-in-a-togo-village.html, accessed September 28, 2022.

[6] “3 ARE CONVICTED IN TOGO OF KILLING AMERICAN: Three residents of the West African country of Togo have been found guilty of killing a 23-year-old Peace Corps worker from Oneonta, N.Y. in June, a spokesman for the Togo mission to the United Nations said yesterday,” The New York Times, September 20, 1984, https://www.nytimes.com/1984/09/20/world/3-are-convicted-togo-killing-american-three-residents-west-african-country-togo.html, accessed September 28, 2022.

[7] Summary taken from Yaco, Murder in the Peace Corps.

[8] Summary taken from Yaco, Murder in the Peace Corps.