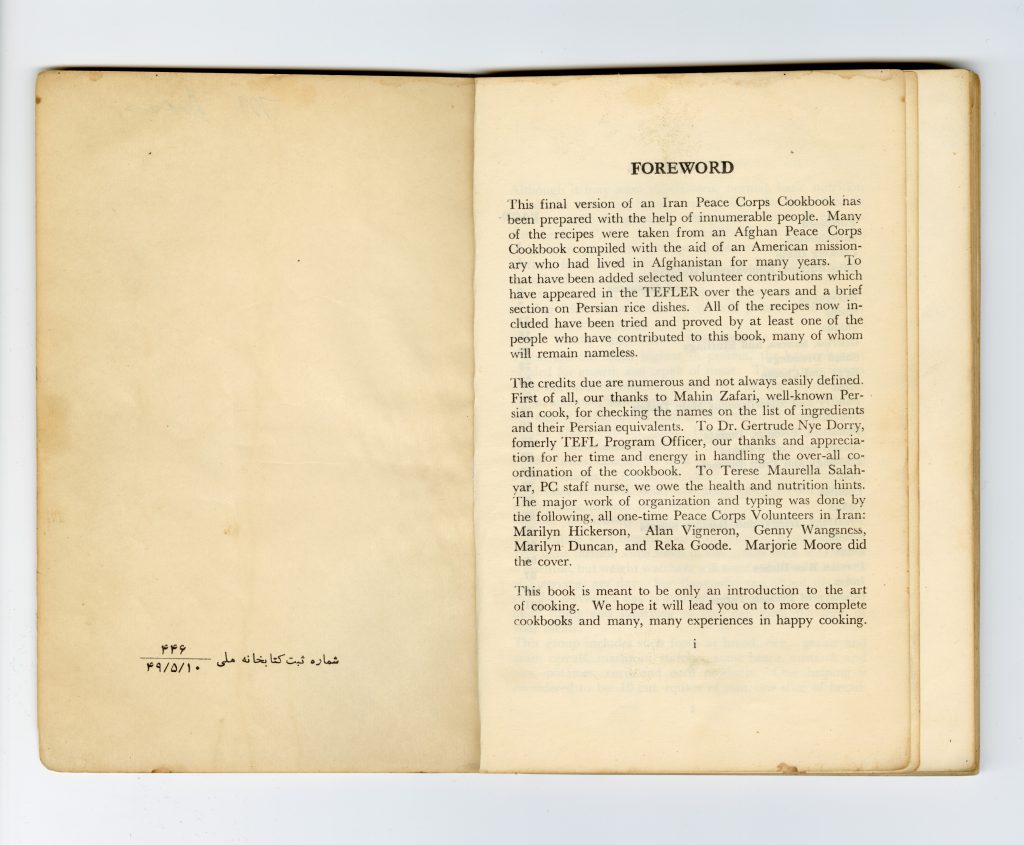

As I skimmed through our newest accession–a collection of correspondence, photographs, and books donated by a PCV who served in Iran from 1964-1968– at the Peace Corps Community Archives, a flash of red caught my attention. At first glance a charming–yet unassuming–text, complete with an advertisement for Pan Am’s in-flight meal service on the back cover, Cookbook: Peace Corps · Iran seized my attention, and here is why:

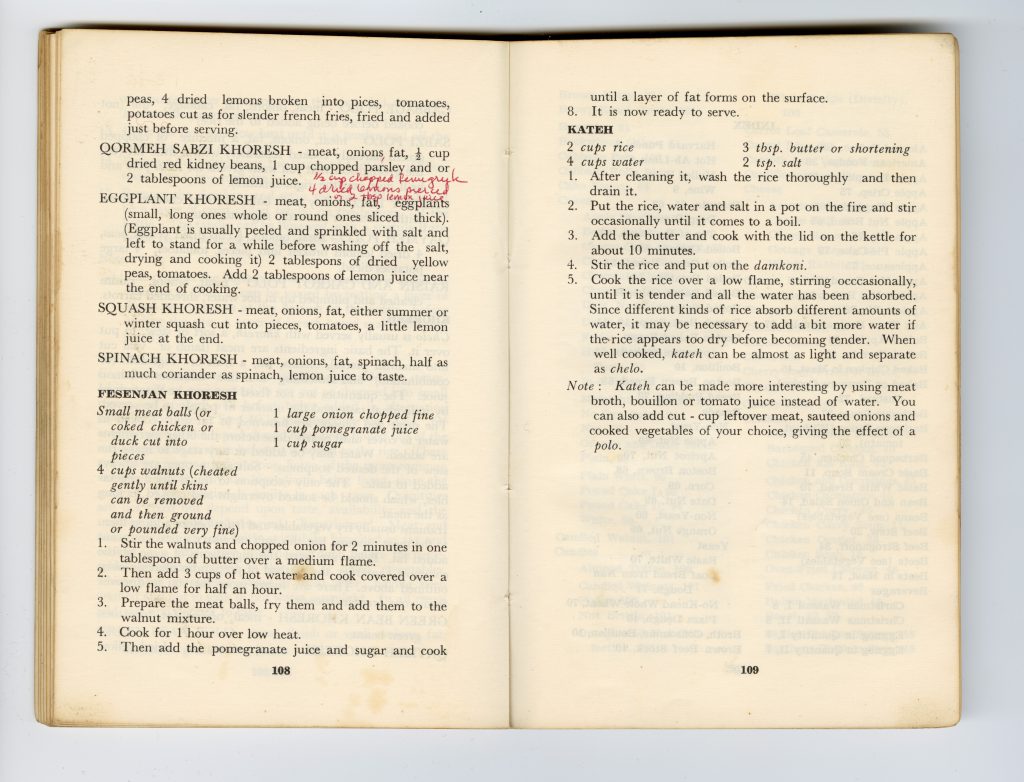

The original recipe for Qormeh (more commonly spelled Ghormeh, meaning fried in Azeri) Sabzi (the Farsi word for herbs) Khoresh–among the “most famous and common rice-based food products in Iran”–calls for sautéing “meat, onions, [and] fat,” then adding “1/2 cup dried red kidney beans,” followed by a low and slow simmer for several hours. [1] The stew is then garnished with “1 cup chopped parsley and or 2 tablespoons of lemon juice.”

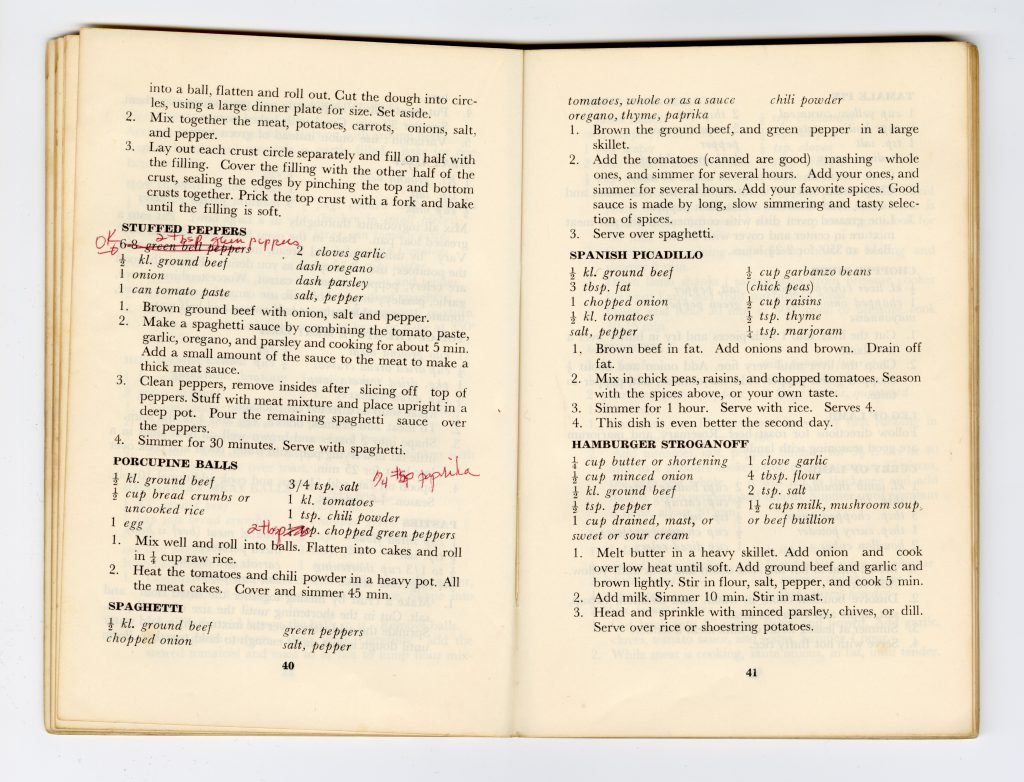

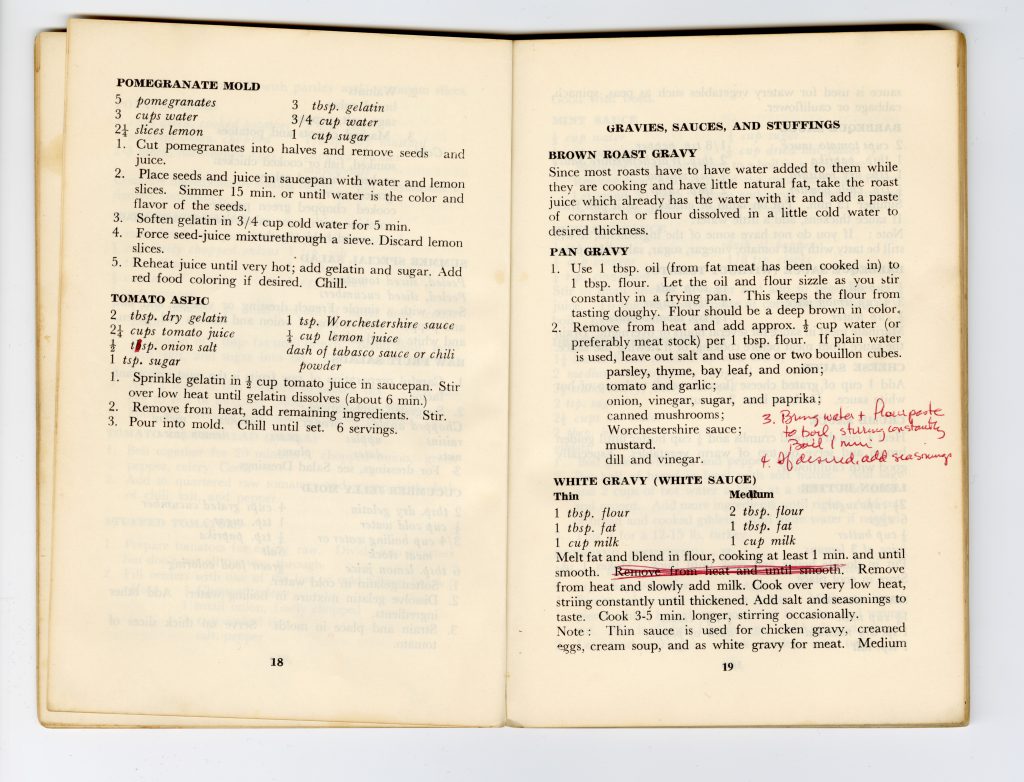

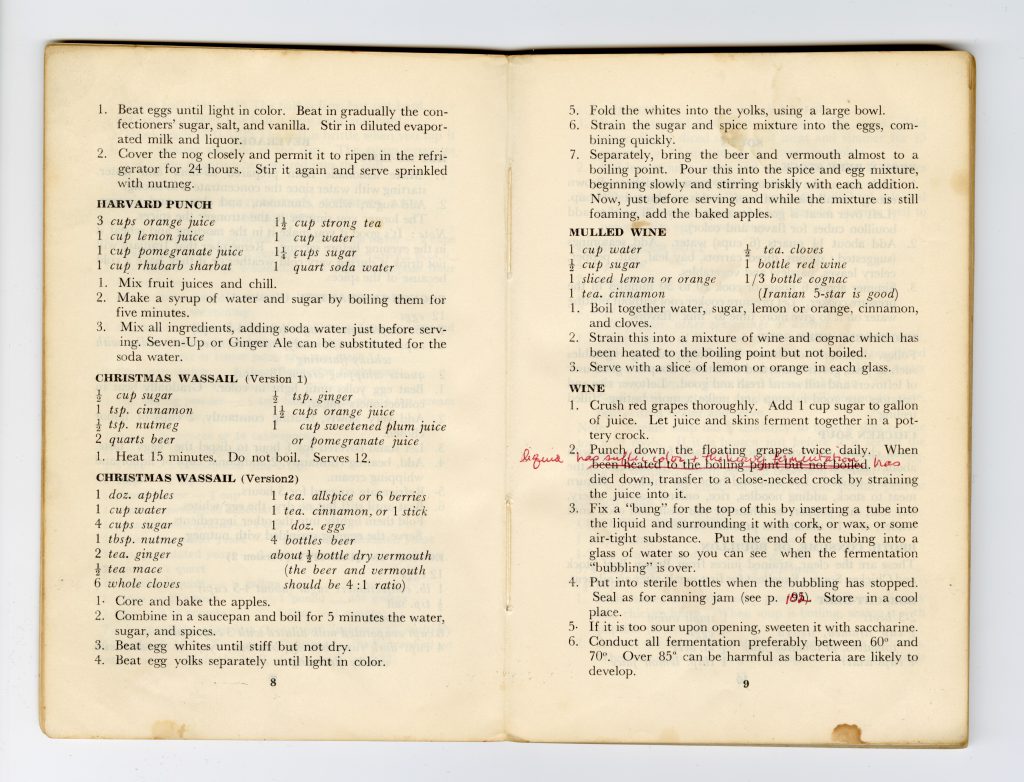

In the meager margins between recipes, however, someone had tweaked the recipe for Qormeh Sabzi Khoresh in red pen, suggesting that “1/2 cup chopped fenugreek, 4 dried lemons pressed or 2 tbsp lemon juice” be added to the recipe. This was not an anomaly; in fact, other recipes were modified throughout the cookbook with the same distinct red ink.

The cookbook contains recipes for a wide variety of staple Iranian dishes, but it also details recipes that would have been more familiar to American palates, such as: stuffed peppers, pan gravy, and porcupine balls. The latter is a cost-effective relic of the Great Depression.

The cookbook further features a comprehensive guide on how to make mulled (or spiced) wine and red wine.

Seeing as a cohort of Iranian cooks, Peace Corps Volunteers, and nutrition specialists all contributed to the cookbook, it is perhaps best read as an iterative artifact–a microcosm for the (ongoing) negotiation between Western and Iranian culinary cultures. On the one hand, the PCV who marked the cookbook in red ink embodies part of this negotiation: an American who embraced Iranian cuisine in a tangible way, via their service in Iran and interaction with Iranians. Their tweaking of Qormeh Sabzi Khoresh was not an attempt to co-opt or Westernize the dish; rather, the addition of fenugreek and dried lemon is actually reflective of the traditional version of the recipe that the PCV likely encountered in their everyday interactions with Iranians.

Houchang E. Chehabi, an Iranian scholar and professor of international relations and history at Boston University, describes traditional Iranian cuisine as “alive and well.” Rice and bread–both consumed as food, while the latter also doubles as a vessel, as makeshift cutlery, and as a general aid to eating–remain staples of Iranian cuisine, often served with a variety of traditional stews, pilafs, proteins, stuffed vegetables, sweets, and the like. The now widespread availability of Iranian food outside of Iran has, according to Chehabi, expanded our collective global palate and “helped relieve the monotony of life.”

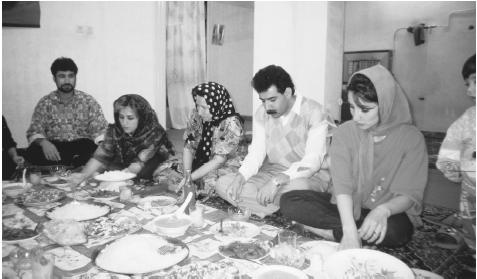

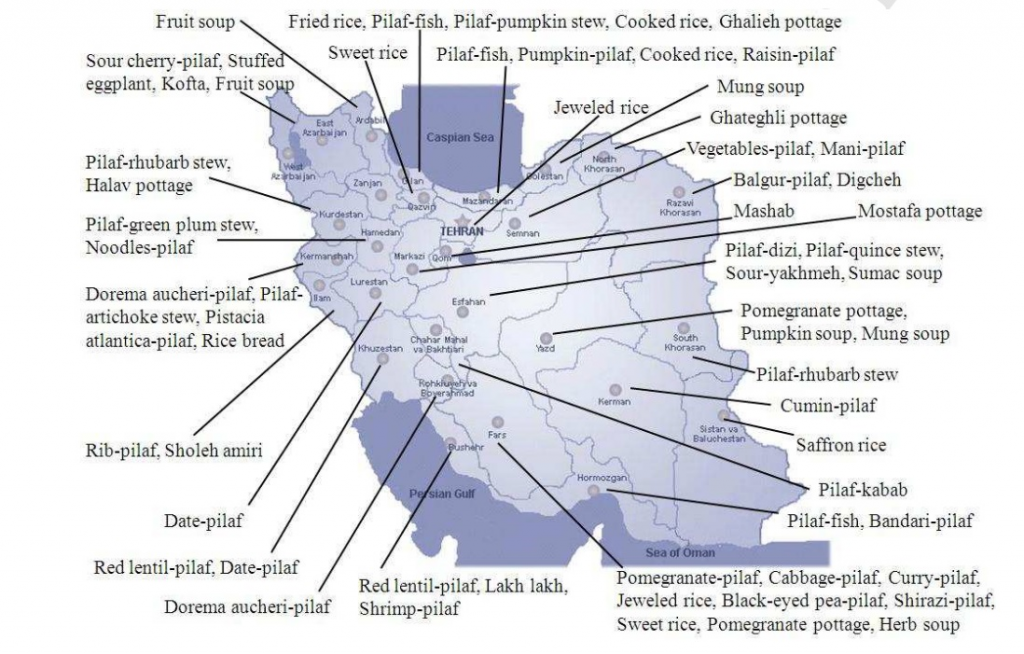

The centrality of rice and bread in Iranian cuisine cannot be overstated; however, the image above illustrates regional variations in their preparation.

On the other hand, Iranian culinary culture has been shaped by Iranians’ interaction with outsiders and their respective cuisines, a process that predated the Peace Corps and the publication of this cookbook in the 1960s. Indeed, during the Qajar reign (1789-1925), elite Iranians at Court began adopting new culinary habits from Westerners, and these habits subsequently spread to the middle class and then to the “rest of the population in a process that is not complete–and perhaps never will be.”

Exemplified in the images above, the traditional Iranian sufra (food spread) was colorful, decorative, and dishes were served concurrently rather than in successive courses. Moreover, Iranians generally enjoyed their food atop embellished carpets, and food was to be consumed with the right hand–sans cutlery. In Qajar palaces, food was prepared by a permanent cooking staff in a kitchen some distance from the living area where it was presented and consumed.

Iranians embraced outside culinary habits in earnest during the 1900s. A 1928 decree issued during the Reza Shah period, for example, outlined several sweeping changes that Tehrani restaurants would be required to implement, including: seating around a table on chairs; containers for dispensing salt, pepper, mustard, and sumac; and strict use of cutlery, thus forbidding patrons from eating with their hands. Just before the inception of the Peace Corps, the consumption of traditional meats–chiefly camel and mutton–in Iran had been superseded by beef and veal, and today chicken–once a delicacy–is consumed ubiquitously. Immediately following the Iranian Revolution (1978-1979), however, food establishments that served western-inspired food and were operated by non-Muslims had to put signs in their windows to “alert those Muslims who considered non-Muslims, and therefore any food handled by them, as najis (ritually impure).”

Despite these changes, and especially since the 1990s, the dual westernization and resilience of Iranian cuisine remains evident; the scent of hamburgers on the grill and pizza in the oven drifts from fast food chains and global food courts scattered throughout Iran’s major cities, a contrast to the age-old aromas that flow (though not as numerously) from higher-end restaurants, street vendor stalls, and Iranian homes. Here, friends and family still sit atop Persian rugs, preferring their right hand to cutlery, as they enjoy an abundant feast (sometimes followed by a period of fasting). Until I have the privilege to experience Iranian cuisine in Iran, I look forward to trying this PCV’s version of Qormeh Sabzi Khoresh–with the addition of fenugreek and dried lemon–in my own home, and I hope you will do the same. Share your favorite recipes with us below, especially those that warm you up on a cold winter day!