Sarah Leister is an anthropology graduate student in Dr. Adrienne Pine’s Craft of Anthropology I course (ANTH-601). This blog post was written in fulfillment of a course assignment.

This blog post will analyze two items from the AU Archives associated with Margaret (Peggy) Gleeson’s volunteer services in the Peace Corps. Gleeson was a nurse who joined the Peace Corps in 1963, just two years after it was founded by President John F. Kennedy. She volunteered in a small village in Colombia called Fusagasugá, where she was tasked with teaching classes to Colombian nurses who worked at the local hospital. This post will focus on Gleeson’s Peace Corps training before she went to Colombia by analyzing two documents: the training manual and her biographical sketch. These documents highlight the political context of the Cold War and how Gleeson and her fellow volunteers felt about their upcoming Peace Corps service.

Gleeson’s Peace Corps training syllabus.

In the early 1960s, Cold War tensions were high. The Cuban Revolution had succeeded in 1959, and the 1961 CIA-led Bay of Pigs invasion that attempted to reverse it had failed. The U.S. aimed to prevent a supposed threat of communism in other Latin American countries. This imperial project coincided with updated Social Darwinist ideologies proposed by U.S. economist Walt Whitman Rostow that placed Latin American countries (and especially the indigenous communities within them) in an earlier stage of development and modernity than the United States (Geidel 2010).

It is against this political backdrop that Gleeson embarked upon an intensive Peace Corps training program in 1963 at Brooklyn College. She was a member of the first group of nurses to be sent to Colombia by the Peace Corps. According to the program’s syllabus, the training included courses on common diseases in Colombia, Colombian history, Spanish language, and ten sessions on “The Challenge of Communism.”

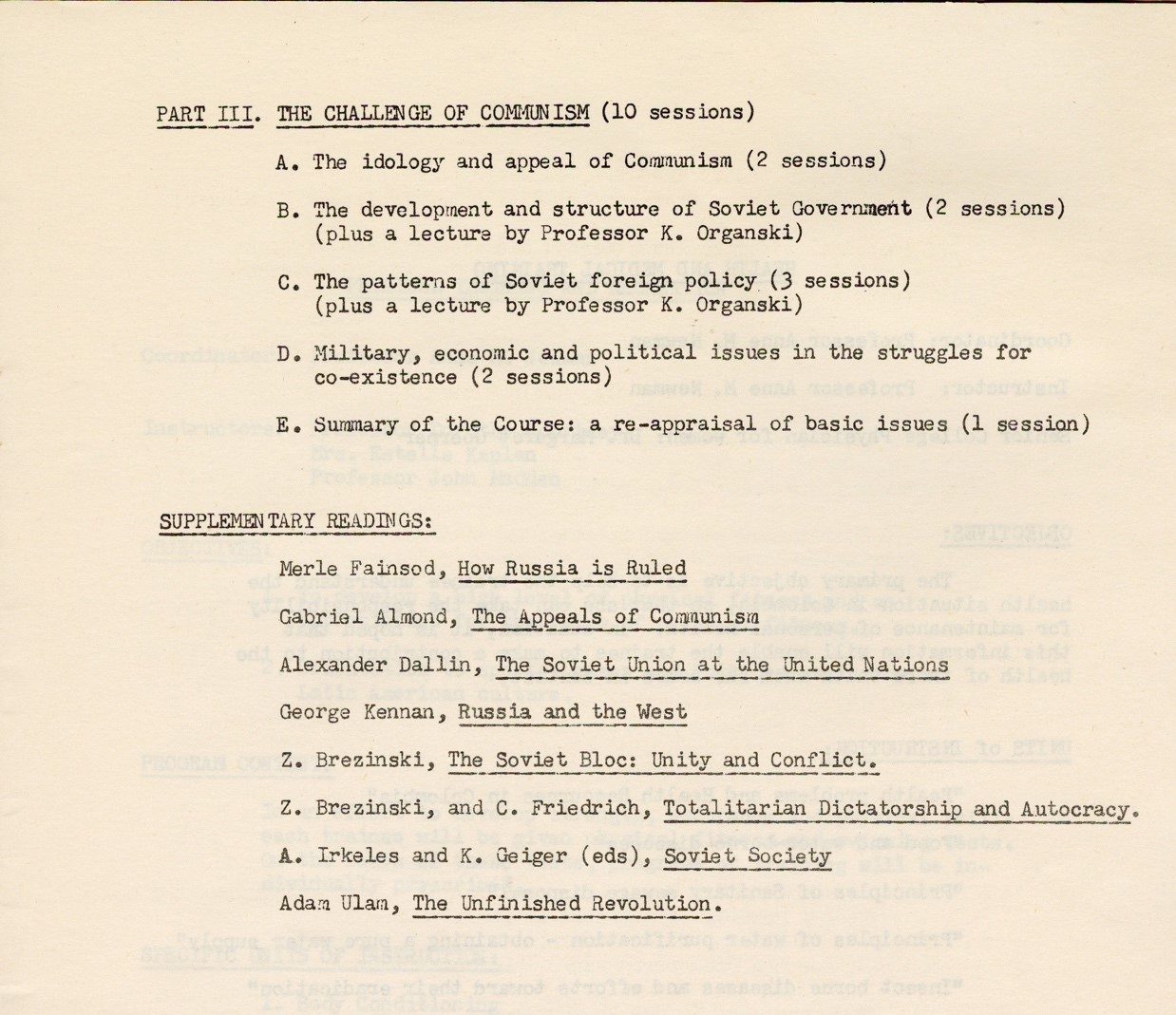

As I looked through the Peace Corps Training Program syllabus, I was surprised to see that Brooklyn College, rather than a U.S. governmental entity, was responsible for training the Peace Corps volunteers. Fernando Purcell and Marcelo Casals (2015) point to the crucial role of U.S. universities in offering training during the Cold War, which were known to give volunteers “theoretical and practical knowledge about modernity and community development, along with a reinforcement of ideological values that were defended during the Cold War” (2). The Brooklyn College syllabus includes readings by staunch anti-communist Zbigniew Brzezinski—an advisor to President and Peace Corps founder John F. Kennedy. It explicitly frames communism as a threat and focuses on the study of Soviet models while glossing over the “great variety of revolutionary models” in Latin America (Purcell and Casals 2015).

The communism section of the Peace Corps training syllabus.

Also in the syllabus, a letter to the volunteers from the Office of the Mayor of New York City states “We in New York City are proud that one of our great municipal institutions is becoming part of the world-wide efforts of the Peace Corps to help the underprivileged peoples of the world.” Similarly, most of the volunteers in Gleeson’s training group stated that their reason for joining the Peace Corps stemmed from a desire to help or serve others.

Gleeson’s biographical sketch featured in a booklet of volunteers’ biographical information.

These documents show an interesting parallel between the U.S. government’s battle against perceived communist threats and the volunteers’ desires to help. They also shine light on the ways in which volunteering, aid efforts, and even social science research have coincided with U.S. imperialism, despite volunteers’ and researchers’ good intentions. While Gleeson and many other Peace Corps volunteers went abroad with a desire to be helpful, a consideration of the broader political context might evoke the title sentiment of Ivan Illich’s provocative speech given to a group of U.S. volunteers in Mexico in 1968: “To Hell with Good Intentions.”

As a white anthropology student from the U.S. who has also traveled to Latin America with good intentions, I am in many ways similar to Peggy Gleeson and other Peace Corps volunteers. This leads me to ask, how can U.S. students, volunteers, and workers analyze their individual intentions within structures of power? To what extent do our intentions matter? How can we make our intentions match up with our actions? How can we combine our intentions and actions in pursuit of international solidarity and social justice, rather than as charity that ultimately reinforces empire?

References

- Geidel, Molly. “‘Sowing Death in Our Women’s Wombs’: Modernization and Indigenous Nationalism in the 1960s Peace Corps and Jorge Sanjinés’ ‘Yawar Mallku.’” American Quarterly 62, no. 3 (2010): 763–86. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2010.0012.

- Illich, Ivan. “To Hell with Good Intentions.” April 20, 1968. Accessed October 29, 2019. http://www.uvm.edu/~jashman/CDAE195_ESCI375/To%20Hell%20with%20Good%20Intentions.pdf

- Purcell, F. and Marcelo Casals. “Espacios en disputa: el Cuerpo de Paz y las universidades sudamericanas durante la Guerra Fría en la década de 1960.” Historias Unisinos 19, no. 1 (2015): 1-11.