One central aspect of service in the Peace Corps is religion. Whether or not Volunteers are religious, they frequently serve in communities that are religious or include beliefs that Volunteers are unfamiliar with. The Peace Corps Community Archive features Volunteers’ experiences encountering new religious traditions, relying on their own faith, interrogating it in light of their service, or all three. This collection of Volunteers’ stories show that Volunteers often experience new or different understandings of religion during their tours.

A Volunteer’s new experiences with religion often starts quickly. In 1970, Edward “Ted” Ferriter, who served in southern India, lived with a Hindu host family while training. Every morning, his host’s wife started her morning with prayers at the family’s altar. [1] When Jessica Vapnek reached the village of Kirumba in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1985, she had to announce her religion. Kirumba primarily had Catholic and Protestant missionaries and infrastructure. Villagers expected her to be one or the other, but Vapnek was Jewish. A previous Volunteer recommended that she say that she was Catholic, as the Protestants did not consume alcohol. Vapnek decided to say that she was Jewish. [2] While she was still accepted, so few people had heard of Judaism that they mostly assumed she was, in her words, “kind of Catholic, but not.” [3]

Other Volunteers have memorable experiences with religion by participating in holidays or seeing holy sites. In northern India, Susan Fortner served in the city of Prayagraj (also known as Allahabad), from 1962-1963. Throughout her service and travels, she interacted with Hindus, Muslims, Jains, Zoroastrians, Christians, and Jews. Fortner was also able to visit religious sites across the country. These included a mosque in Kashmir which held some of Muhammad’s hair, as well as the Kali Temple and a Jain temple in in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta). Additionally, she was able to visit Mother Teresa’s Home for the Dying, though she did not meet its titular founder. [4]

Joanne Trabert, who served in the Guatemalan village of Granados from 1996-1998, experienced several religious ceremonies and holidays. One notable holiday she experienced was Christmas in 1996. In the weeks before Christmas, she and local friends, who were Catholic, decorated their houses together. On the evening of December 24, Trabert went to a Catholic service, ate tamales, and enjoyed fireworks and parties into the wee hours. The next morning, she exchanged gifts with close friends in Granados. That evening, Trabert, two other Volunteers, and some visiting relatives cooked a traditional American Christmas dinner and celebrated with local friends. [5]

Photo of Joanne Trabert receiving a vase from friends in Granados on Christmas Eve, 1996. Unknown, 1996, in photo album, American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

Some religious Peace Corps Volunteers find meaningful ways to practice their beliefs. Marion Oakleaf was a member of the Religious Society of Friends (also known as Quakers). Her Peace Corps service in South Korea from 1966-1967 was simply one part of a life filled with volunteer work and service-oriented jobs. [6] As previously mentioned, Jessica Vapnek was a Jewish Volunteer serving in an area with few to no other Jewish people. During her training, she was able to celebrate Shabbat with other Jewish Volunteer trainees, as well as when she was traveling. [7] After her service, she traveled around Zaire and spoke of her amazement of visiting a synagogue and meeting with a rabbi; the two even had mutual friends. [8]

Other Volunteers consider their beliefs in different ways as a result of their service. This was particularly the case for two sets of Volunteers who fell in love and married early in their service. In early 1964, Bill VanderWerf and Barbara Jones met at training in Oregon to serve in Iran. [9] They married in Iran that September. [10] When they decided to marry, they wrote their parents, but they also had to tell them about new religious transitions. VanderWerf had switched from Catholicism to Protestantism long before his service and simply had not told his parents. However, Jones decided to leave her childhood denomination, Christian Science, during training in Portland, though she still considered herself a Protestant. Jones now considered Christian Science to be too rigid and insular for the more diverse world that she was encountering. [11]

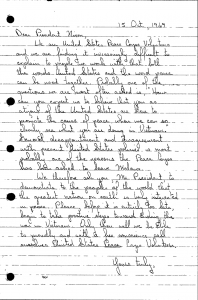

Arnold Zeitlin and Marian Frank met in California during training for Ghana in the summer of 1961; they married that December. Zeitlin was Jewish, while Frank grew up a Presbyterian but had since become more generally spiritual. When they became engaged, they wrote letters to their own parents and to their fiancée’s parents to introduce themselves and ask for blessings. One of their largest concerns was how their families would react to an interreligious marriage. In her letters, Frank emphasized the similarity of their beliefs and values. [12] Zeitlin wrote his parents a similar note, emphasizing that he was still very much Jewish, but that “I believe deeply that we will be stronger because of our diversity.” [13] Through the Peace Corps, these two couples not only fell in love but thought about their religious beliefs in new and different ways.

Arnold and Marian Zeitlin (bottom left) after their marriage, sitting with the Ghanian teachers they worked alongside. Unknown, 1962-1963, in scrapbook, undated, American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

Peace Corps Volunteers encounter or reconsider many ideas during their service, and religion is no exception. Whether visiting a holy site, finding ways to practice their faith overseas, or in day-to-day interactions, Volunteers often have new experiences or understandings of religion during their service.

[1] Edward Ferriter, “My Peace Corps Story, India 1970-1972.” American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[2] Jessica Vapnek to friends and family, August 16, 1985. American University Archives, Washington, D.C. Vapnek’s collection also includes a letter of advice from previous Volunteers in Kirumba, which is the subject of a different blog post [https://blogs.library.american.edu/pcca/to-the-new-volunteer-helpful-letters-in-a-new-place/]

[3] Jessica Vapnek to friends and family, October 7, 1985. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[4] Susan Fortner, “India: A Memoir,” 3, American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[5] Joanne Trabert to friends, January 9, 1997. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[6] Marian Oakleaf obituary, April 3, 2016. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[7] Jessica Vapnek to friends and family, August 25, 1985; Jessica Vapnek to friends and family, February 16, 1986. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[8] Jessica Vapnek to friends and family, August 9, 1987. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[9] Barbara VanderWerf, “Four Seasons: A Khareji in Iran in the 1960s,” (unpublished manuscript, 2021), 7-13.

[10] VanderWerf, “Four Seasons,” 101-102.

[11] VanderWerf, “Four Seasons,” 101-102.

[12] Marian Frank to her parents, October 30, 1961; Marian Frank to Morris and Bess Zeitlin, October 31, 1961. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[13] Arnold Zeitlin to Morris and Bess Zeitlin, October 30, 1961. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.