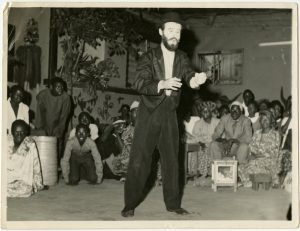

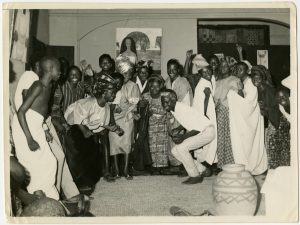

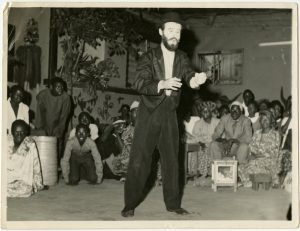

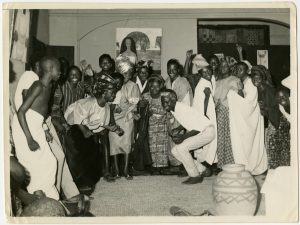

In his capacity as tour manager for the University of Ibadan’s Shakespeare Traveling Theatre troupe, Tom Hebert brought renowned productions—like Twelfth Night, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Hamlet among others—to audiences throughout Nigeria. The pictures above illustrate a core tenet of Shakespearian performance: audience interaction, which was anything but lacking in West Africa during the 1960s. In a recent blog post, Hebert recalls that millions of Nigerian students were required to study Shakespeare as part of their secondary education; consequently, audiences numbering in the “thousands would mouth the lines in an audible susurrus” during shows. [1] Hebert also came to understand that British colonialism and an entrenched caste system overshadowed the educational merits of theater: “literate African kids wandering the streets with nothing to do, and nowhere to go.”

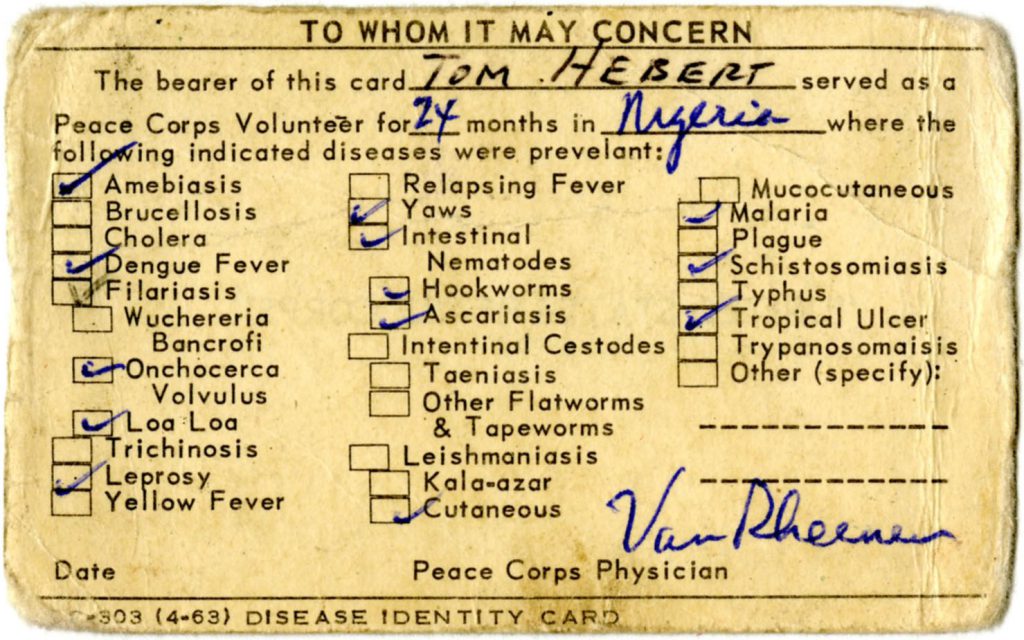

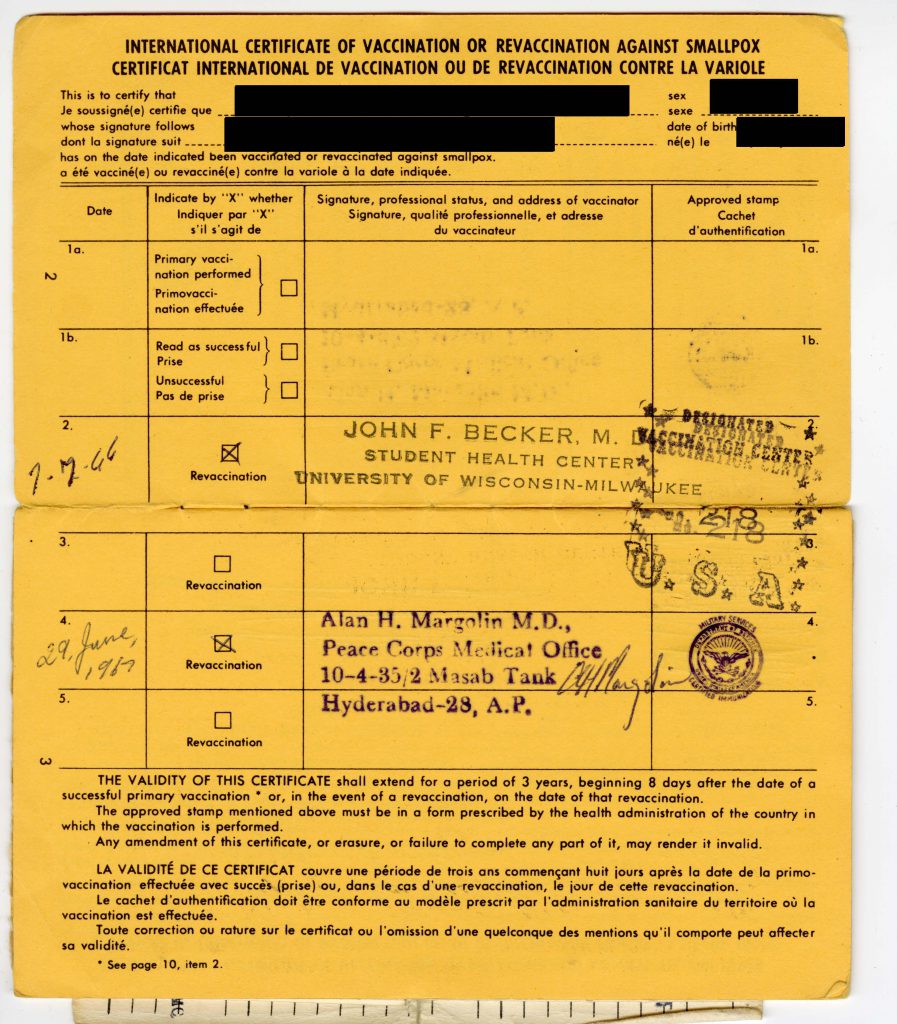

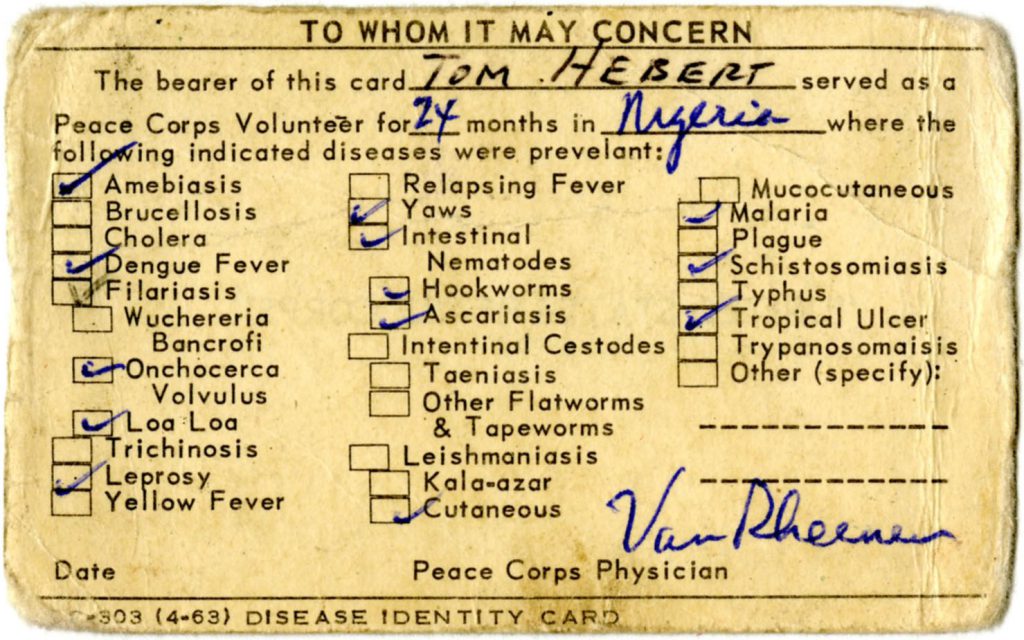

In 1964, after two years of service as a Peace Corps Volunteer (PCV), the time had come for Hebert to return to the United States. Addressed “To Whom It May Concern,” a disease identity card (pictured below) marked Hebert’s return:

Disease Identity Card, April 1963, Shelf: 12.03.05, Box: “Tom Hebert,” Folder: “Hebert, Thomas L, Nigeria 1962-1964, Training Materials–Supplies and Medical Information,” Peace Corps Community Archive, American University Library, Washington, D.C.

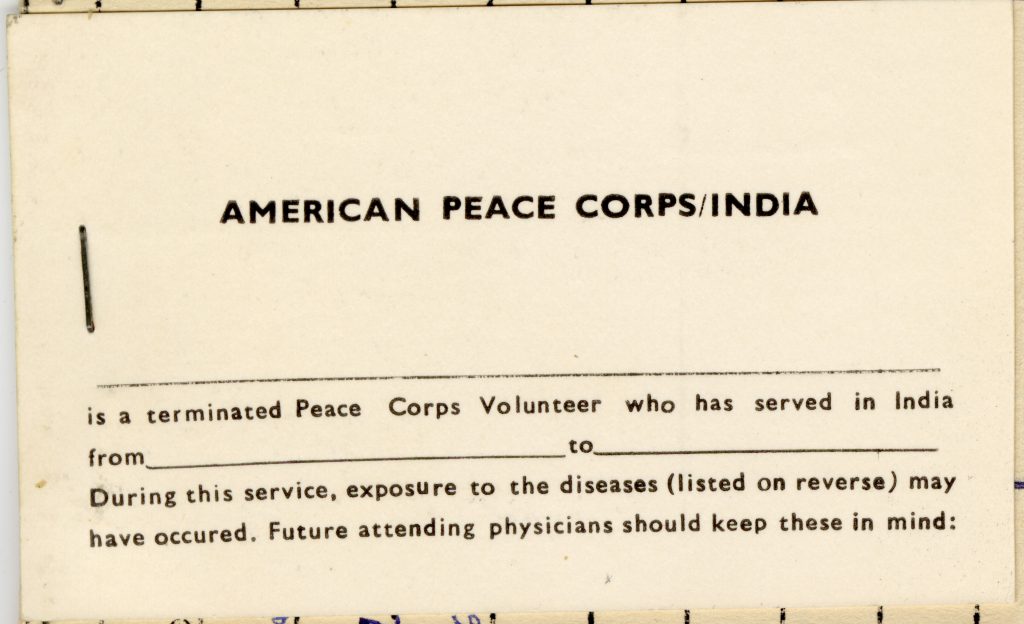

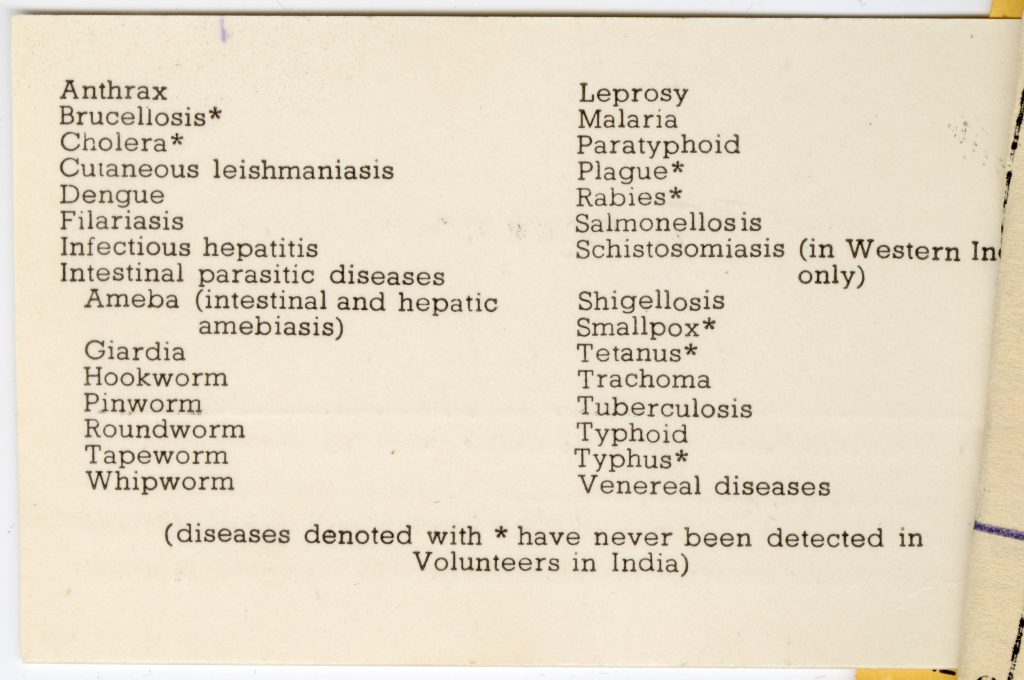

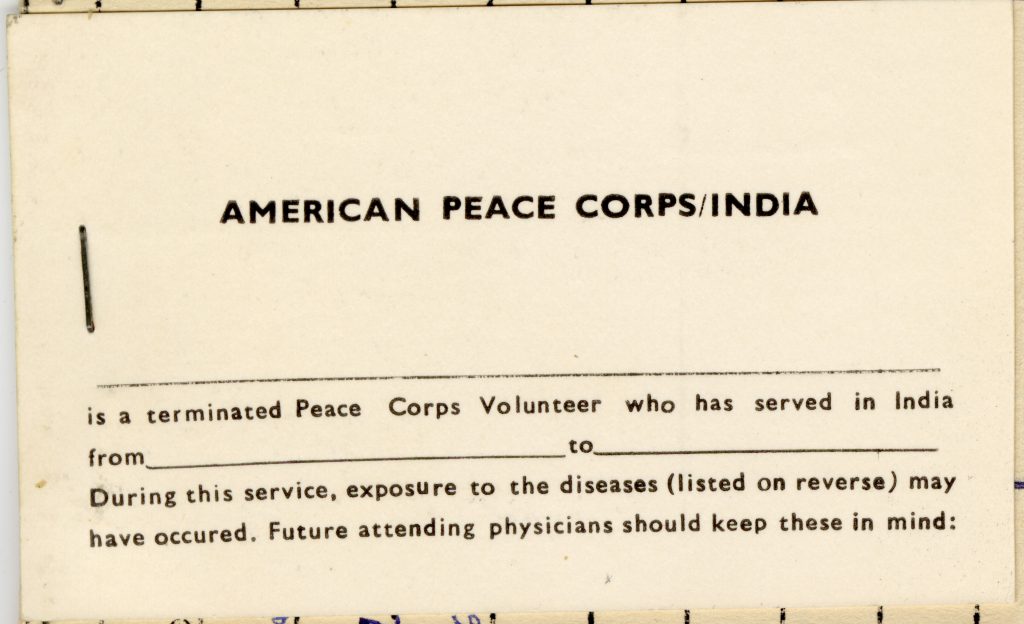

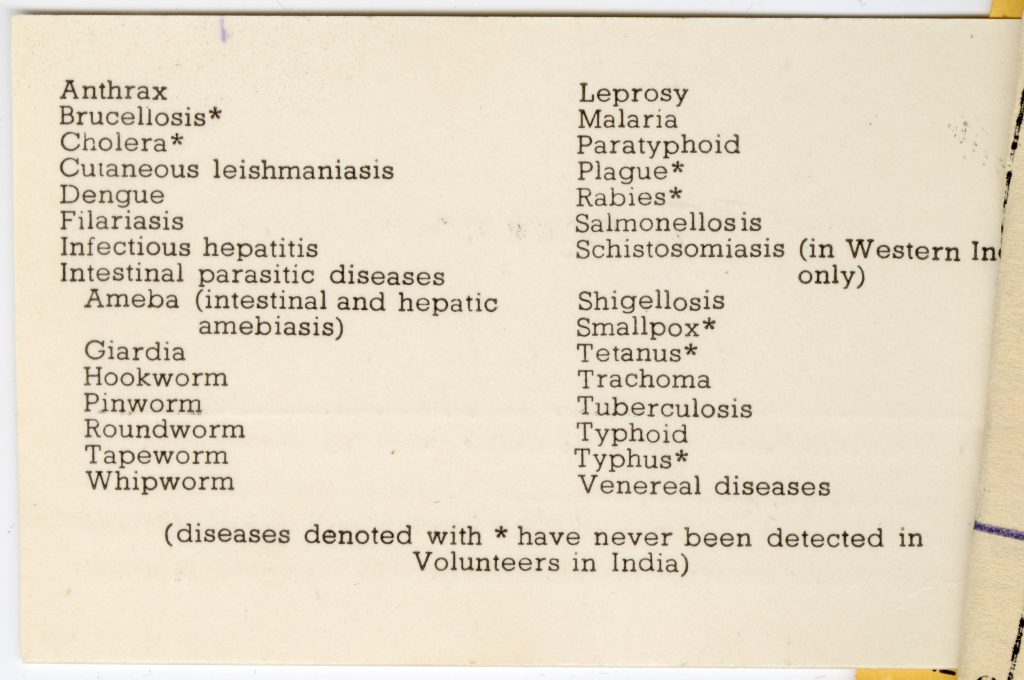

In another example, an unnamed PCV received a similar card upon their return from India in 1968:

Disease Identity Card, 1968, Shelf: 12.03.02, Inquire for Box & Folder Information, Peace Corps Community Archive, American University Library, Washington, D.C.

These cards were a reminder to PCVs as to the prevalence of disease in their country of service. They were also ostensibly a precautionary measure—designed to warn physicians that the returning PCV might well be a public health risk, in which case subsequent isolation, treatment, contact tracing, and the like would become necessary. [2] Thus, in addition to coping with “reentry, readjustment, and reverse culture shock,” returning PCVs further faced the (remote) reality that they themselves might inadvertently bring lethal pathogens—for which there was little protection against—home to friends and family. [3]

An example: there was no vaccine to combat Dengue Fever—one of several diseases that Tom Hebert was potentially exposed to in Nigeria—in the 1960s. To this day, a “safe, effective, and affordable vaccine” for Dengue Fever remains elusive. [4]

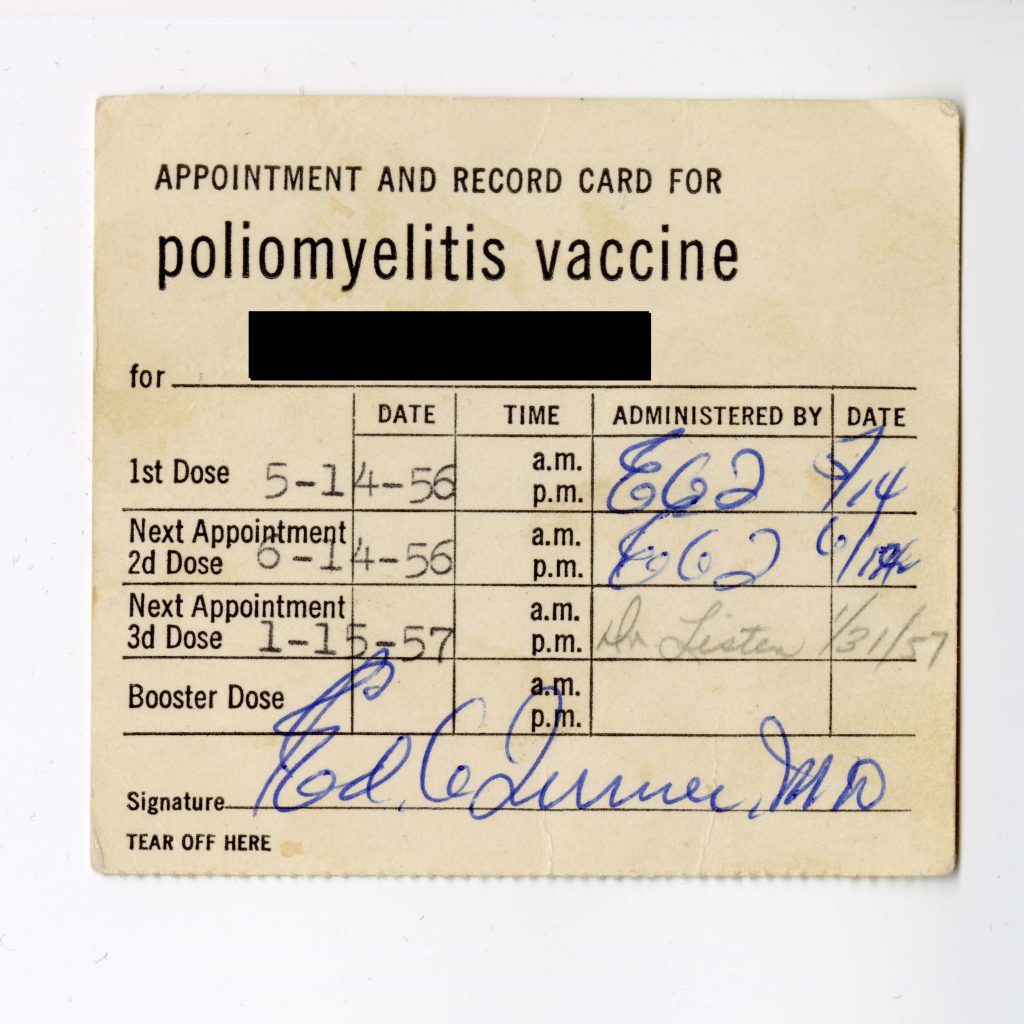

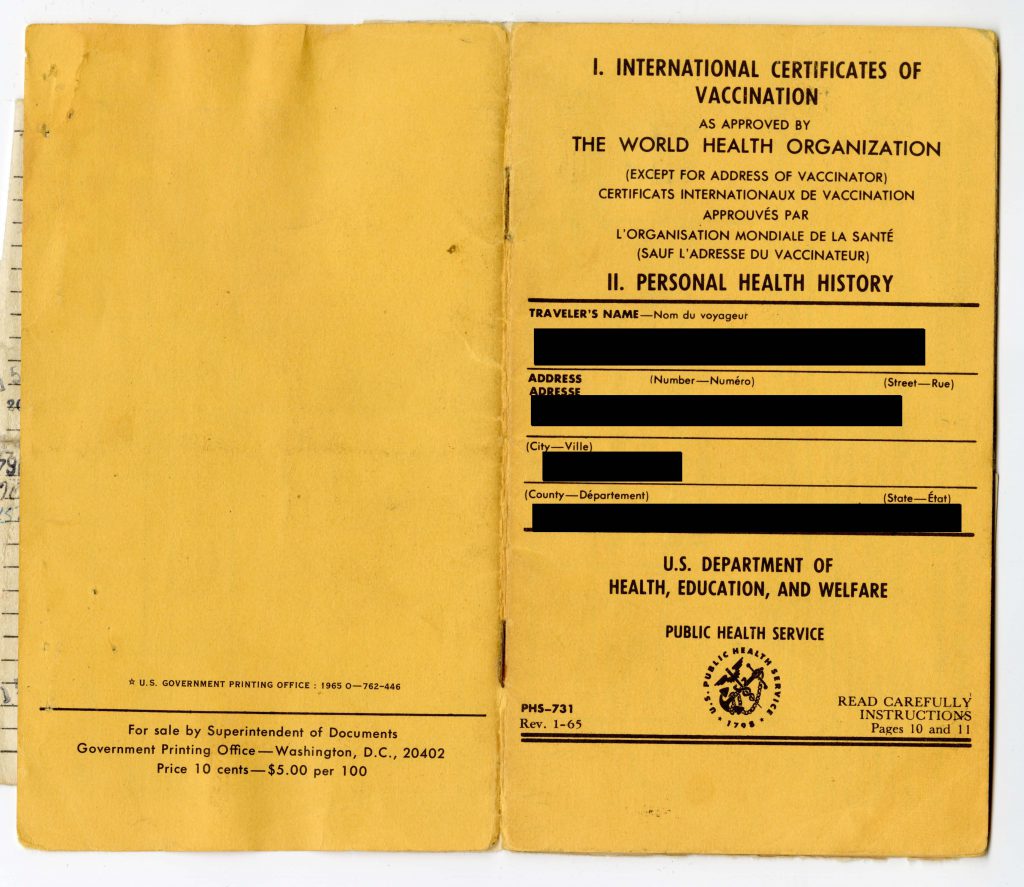

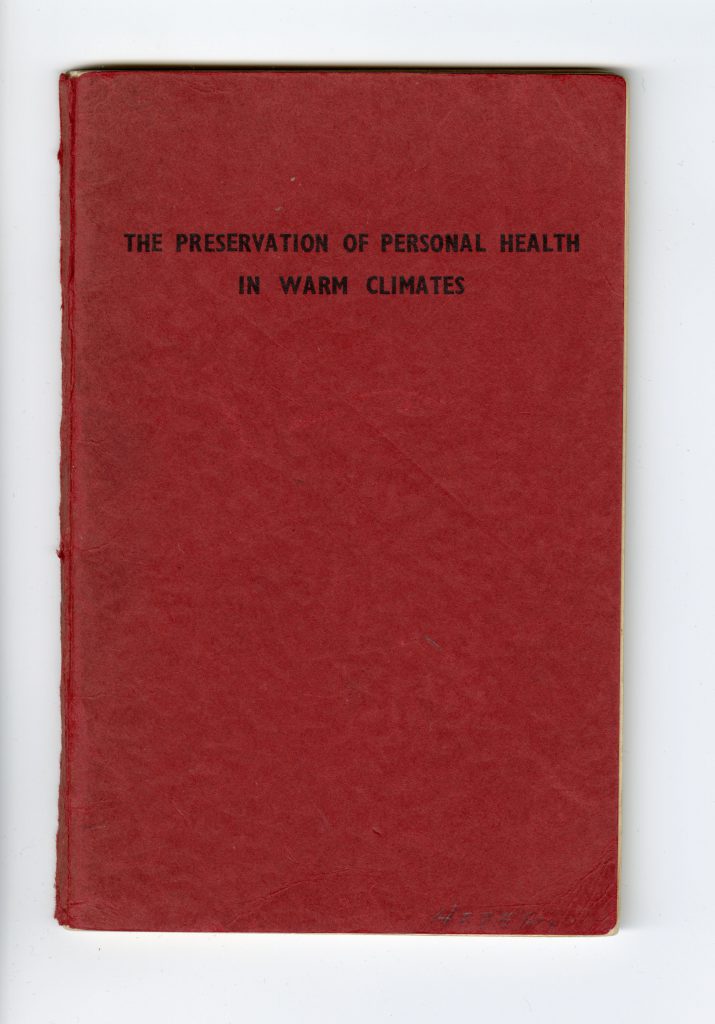

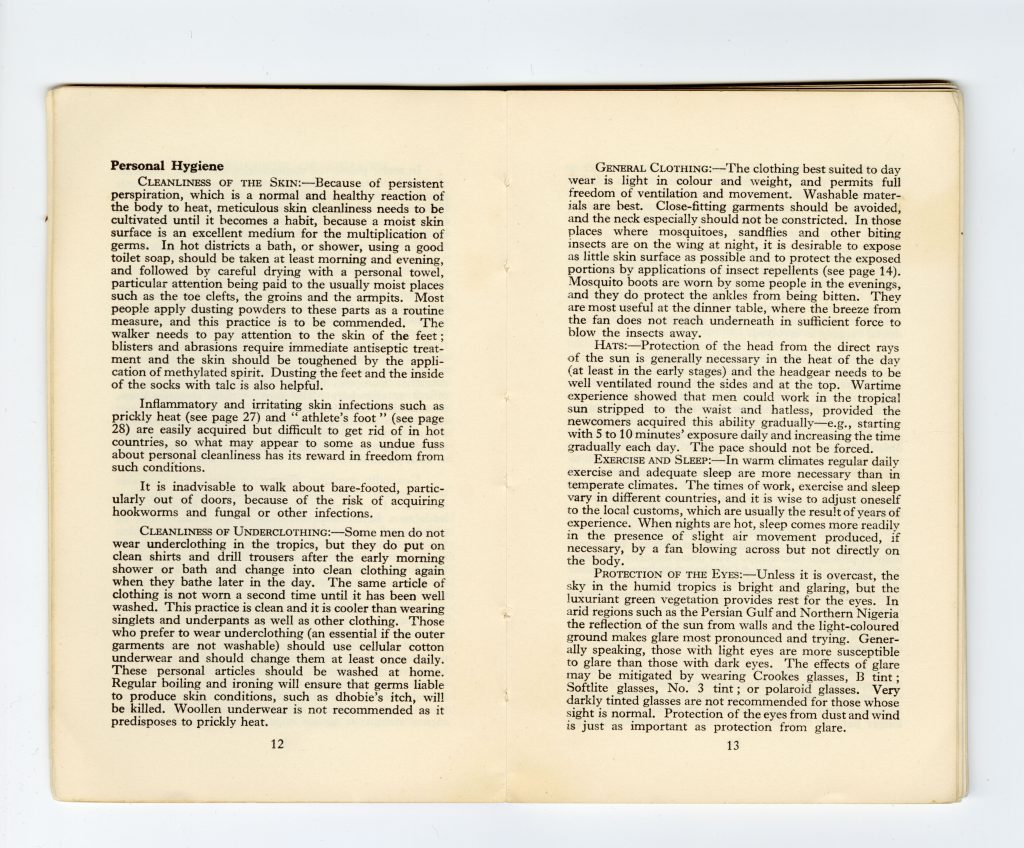

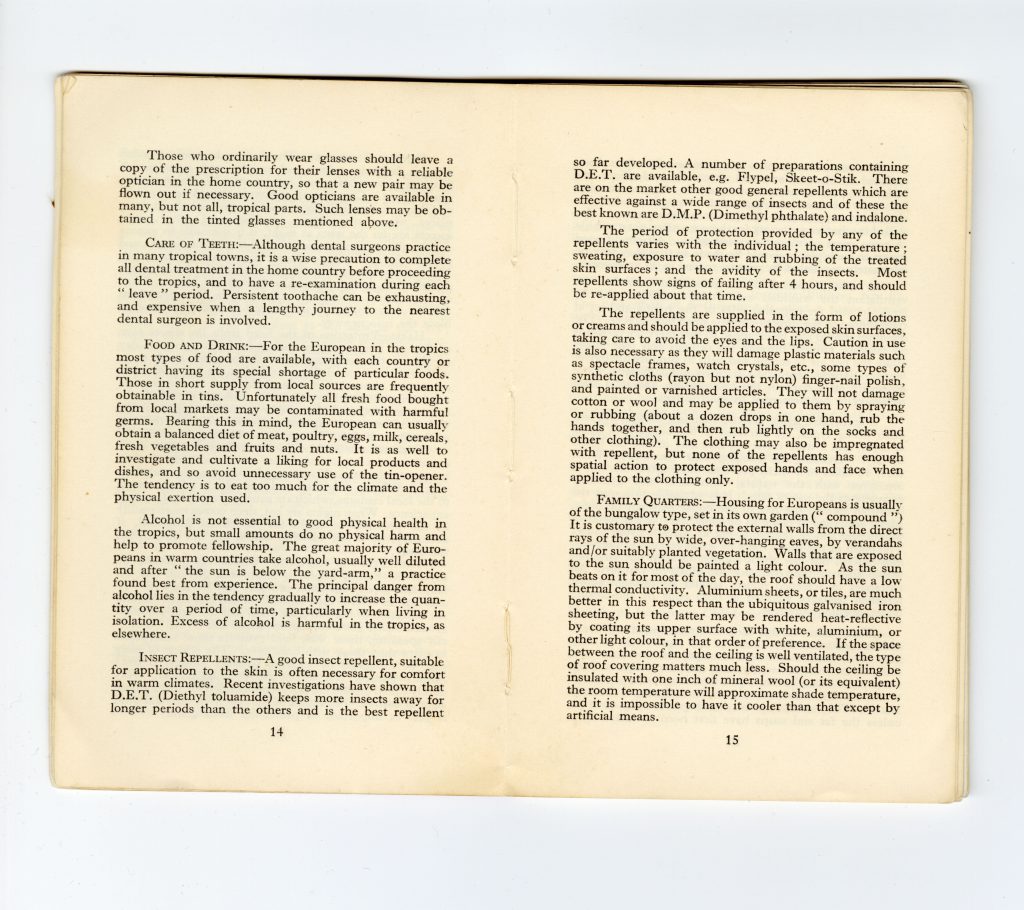

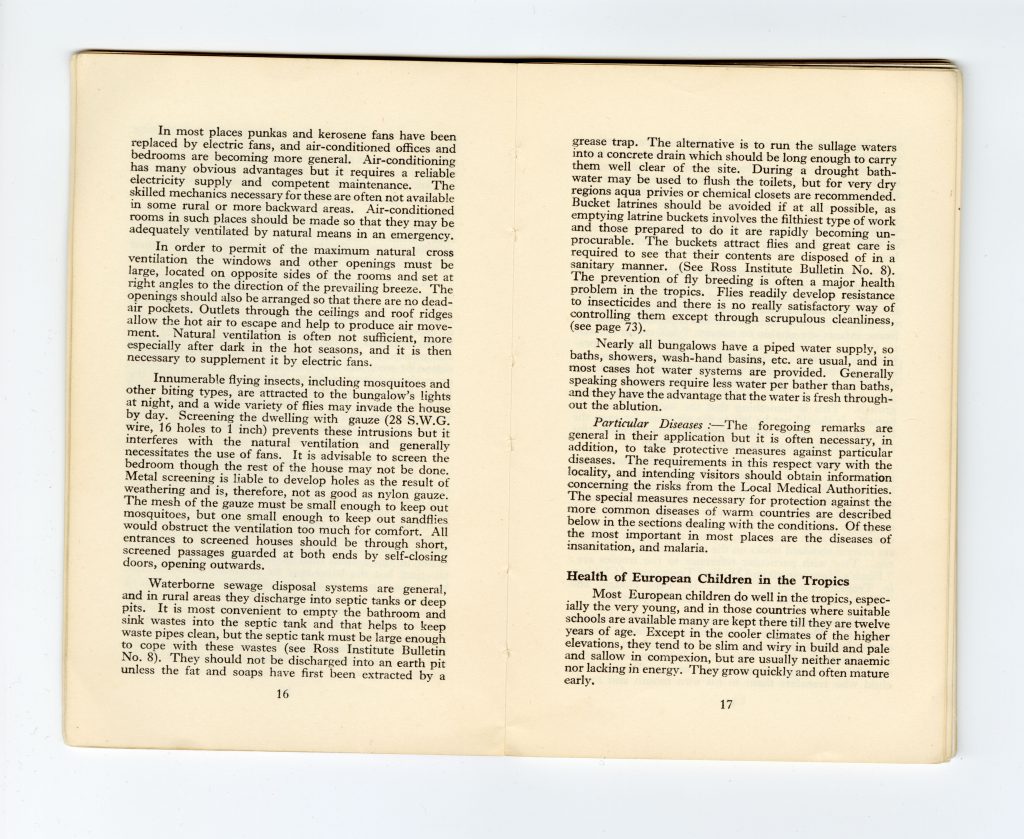

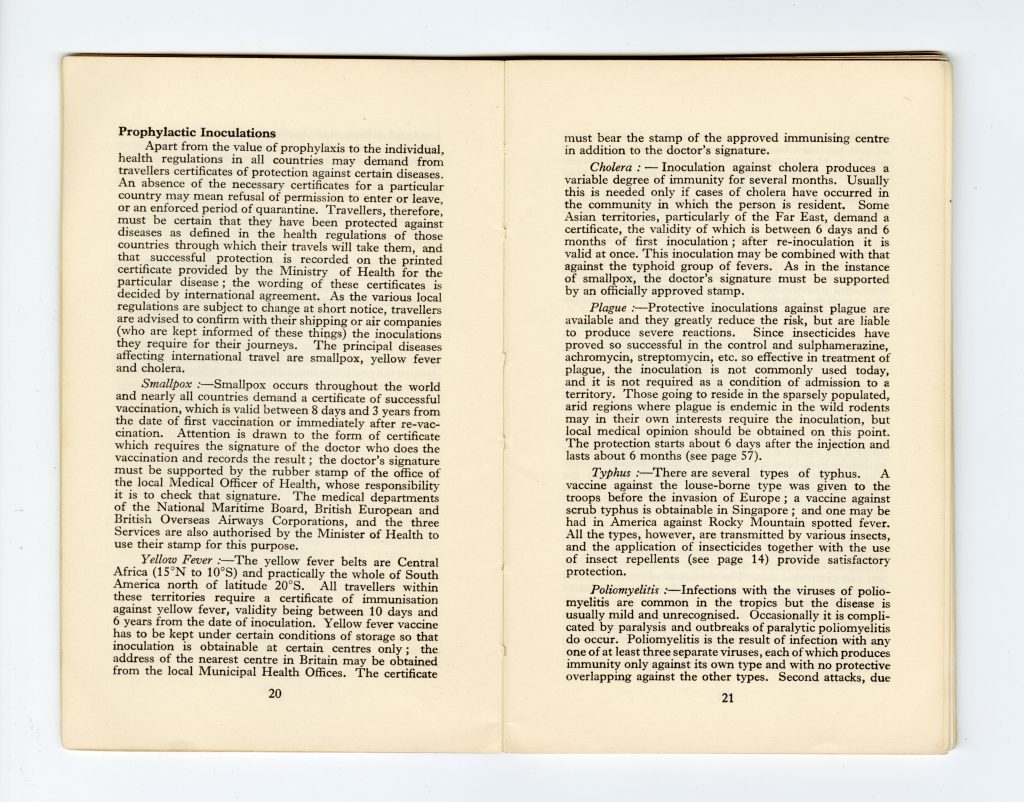

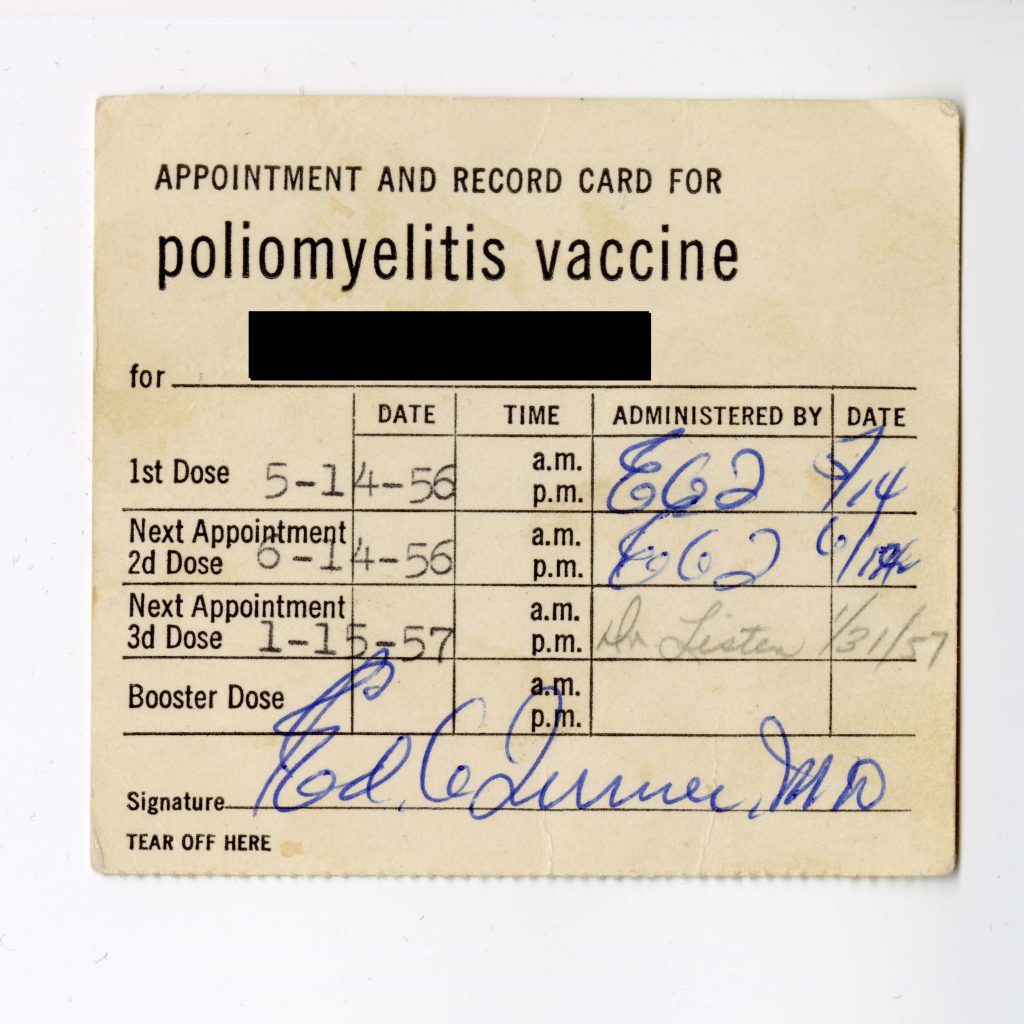

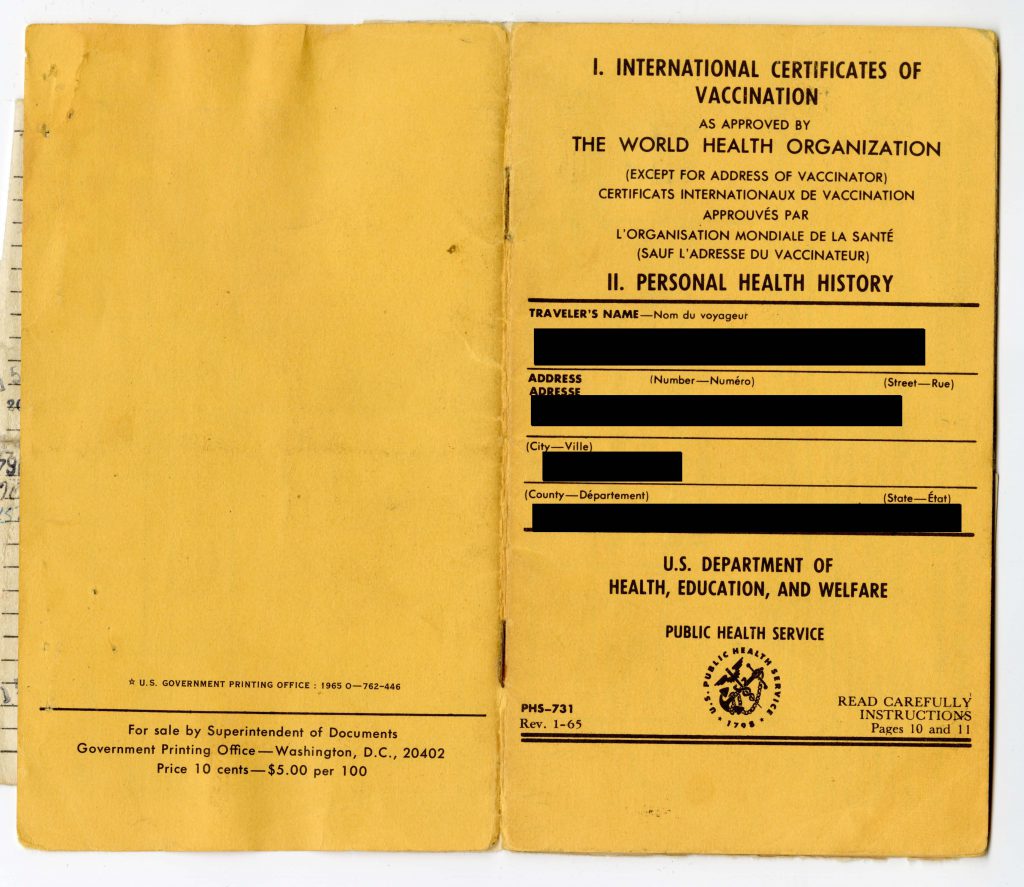

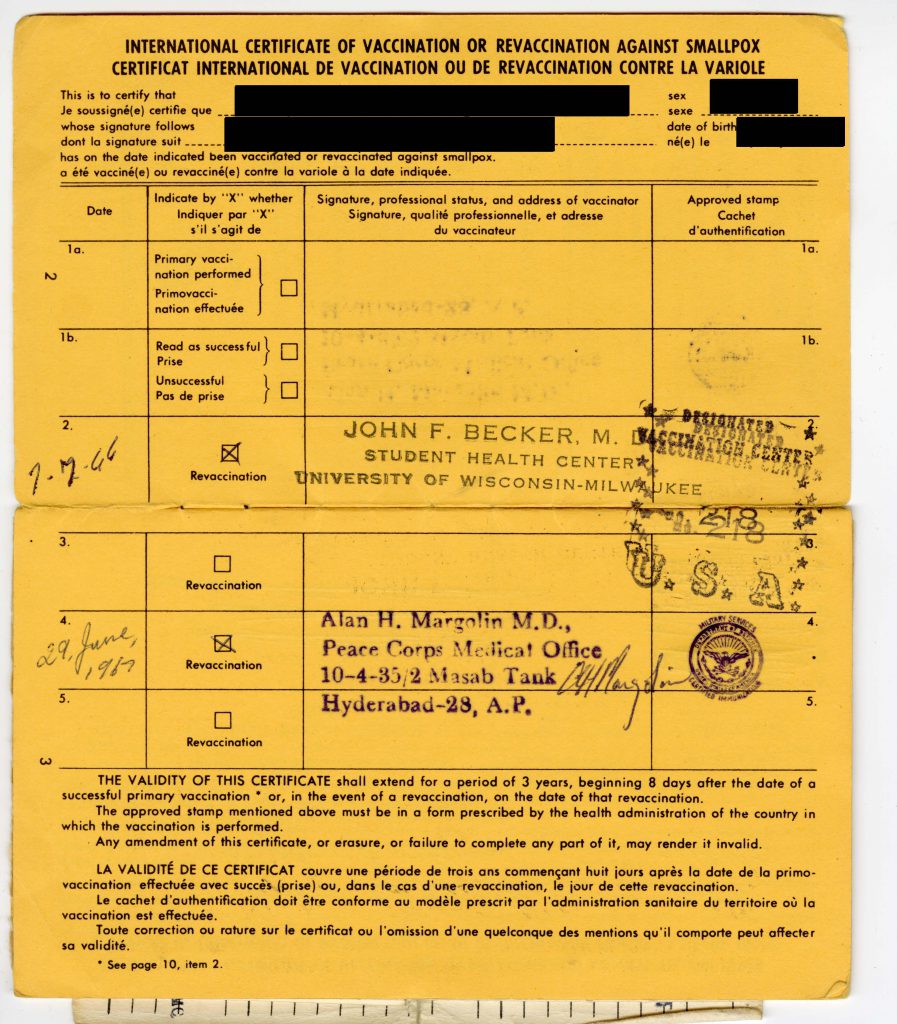

This is not to say that the Peace Corps only took steps to protect PCVs on the back-end of their service. Additional evidence from the Peace Corps Community Archive is revealing; even in the 1960s, the fledgling Peace Corps had a robust front-end health program. It featured preventive medicine (where possible) and pre-departure education designed to reduce disease transmission:

Vaccination Appointment & Record Card, Shelf: 12.03.02, Inquire for Box & Folder Information, Peace Corps Community Archive, American University Library, Washington, D.C.

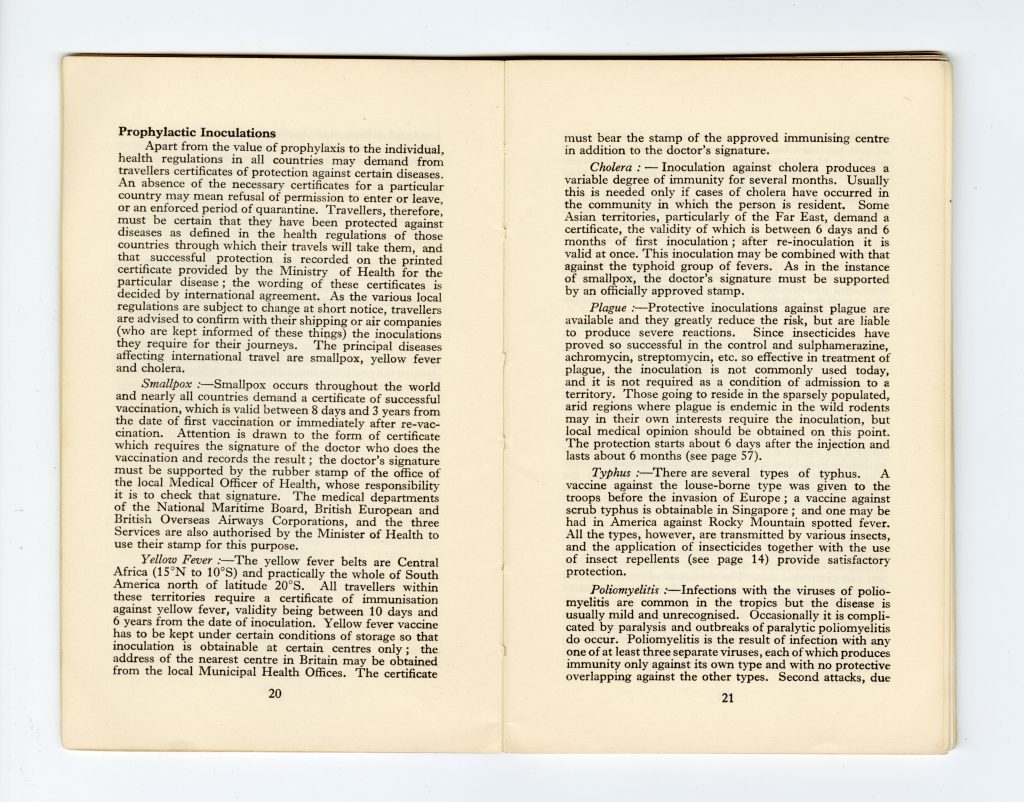

-

-

-

Vaccination Booklet, Shelf: 12.03.02, Inquire for Box & Folder Information, Peace Corps Community Archive, American University Library, Washington, D.C.

PCV Medicine Book, Shelf: 12.03.05, Box: “Tom Hebert,” Folder: “Hebert, Thomas L, Nigeria 1962-1964, Training Materials–Supplies and Medical Information,” Peace Corps Community Archive, American University Library, Washington, D.C.

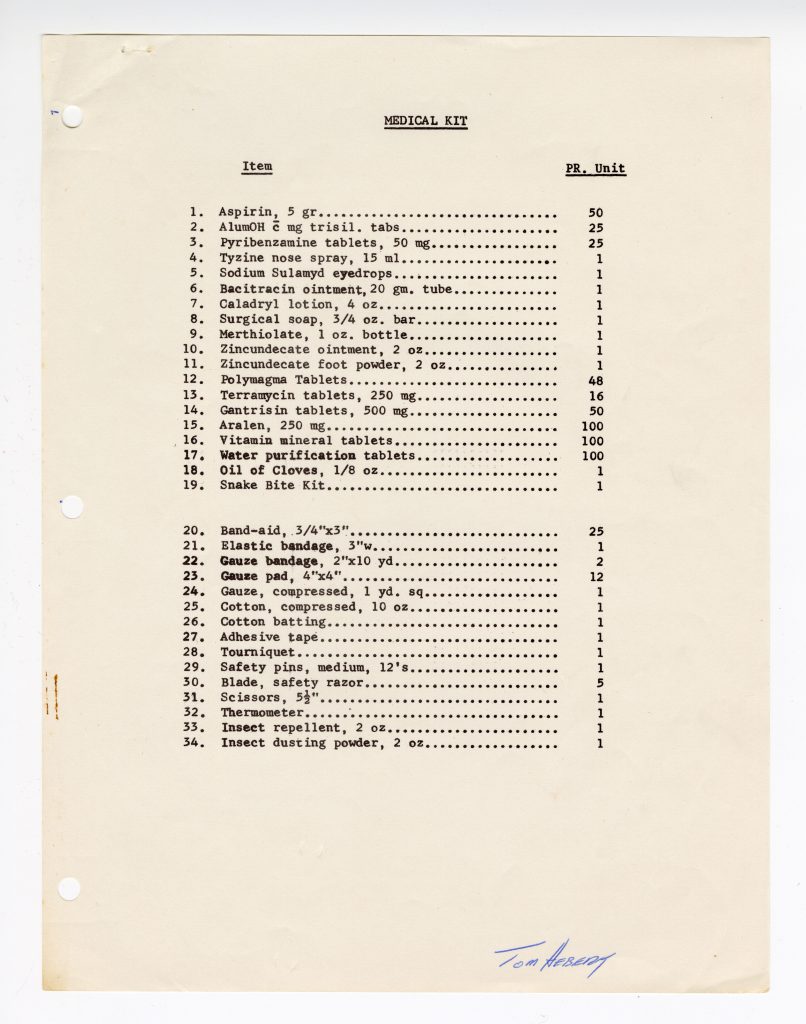

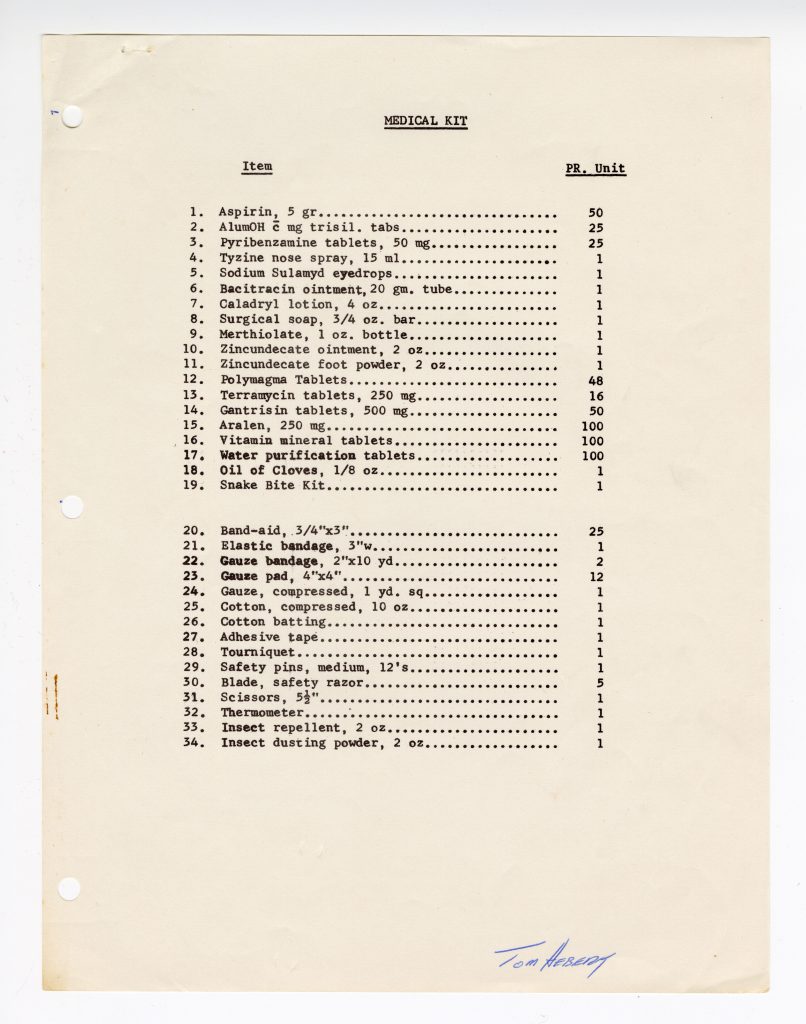

In the case that preventive measures such as vaccination and sanitation failed, the Peace Corps also offered active PCVs reactionary treatment in the form of a standard medical kit:

Peace Corps Medical Kit with Health Guide, ID # 2011.0228.36, Transfer from the Peace Corps, National Museum of American History, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1412958

Medical Kit Inventory, Shelf: 12.03.05, Box: “Tom Hebert,” Folder: “Hebert, Thomas L, Nigeria 1962-1964, Training Materials–Supplies and Medical Information,” Peace Corps Community Archive, American University Library, Washington, D.C.

On balance, the health measures enacted by the Peace Corps—from pre-service medical training and vaccinations, reactionary treatment options during service, and disease identity cards upon return—were largely successful. From 1962-1983, 185 PCVs died during their service; of those 185, 40 died due to illness. For context: some 235,000 PCVs have served in hundreds of countries since the Peace Corps’ inception in 1961.

Relative to the Nigerians for whom he organized Shakespearean performances, Hebert enjoyed a position of privilege in terms of access to healthcare. For many PCVs, the prospect of becoming ill during service or bringing illness back to loved ones upon return was remote; indeed, the public health infrastructure of their home country, the United States, was robust compared to many countries where the Peace Corps operated.

However, what if the opposite were true? What if returning home was seemingly just as dangerous—if not more dangerous—to the well-being of PCVs? In March 2020, following the onset of COVID-19, this seeming impossibility came to fruition as all active PCVs were evacuated back to the United States. [5]

In a blog post for the Pacific Citizen, Kako Yamada—an evacuated PCV who had been serving in Comoros—recounts the abruptness of being evacuated due to COVID-19: [6]

Our plans for the remaining months or years of service vanished as we collected what we could of our belongings — some able to say their good-byes, others not so lucky.

I had been allotted one hour to pack and say my farewells to my host family — leaving my friends, students, teammates and co-workers in the dust.

Yamada did not fully grasp the gravity of the situation until she embarked on the long flight from Comoros—an island country off the coast of Africa—to her home in New York City:

On my layover in Addis Ababa, I saw people in full body suits; on the subsequent plane, flight attendants wore gloves and asked passengers not to help one another. Upon arrival at Newark Airport in New Jersey, a hollow silence echoed. Welcome home.

She also remembers questioning whether the evacuation was justified, especially because the situation in Comoros appeared much less dire (in terms of infection case numbers) than it did in the United States. It wasn’t until May 1 that the first case of COVID-19 was announced in Comoros; by then, in the month and a half since she had returned to New York, “there had been 304,372 reported COVID-19 cases in New York, a number that equated to half the population of Comoros.”

Moreover, in the United States, a crisis of public trust emerged—only compounding the threat posed by COVID-19. The situation rapidly devolved into a multifaceted culture war, one which pinned public health experts against conspiracy theorists and their sympathizers in government leadership. Anecdotal evidence and misinformation were disseminated to discourage mask wearing and promote unproven miracle cures, among other flashpoints of the culture war.

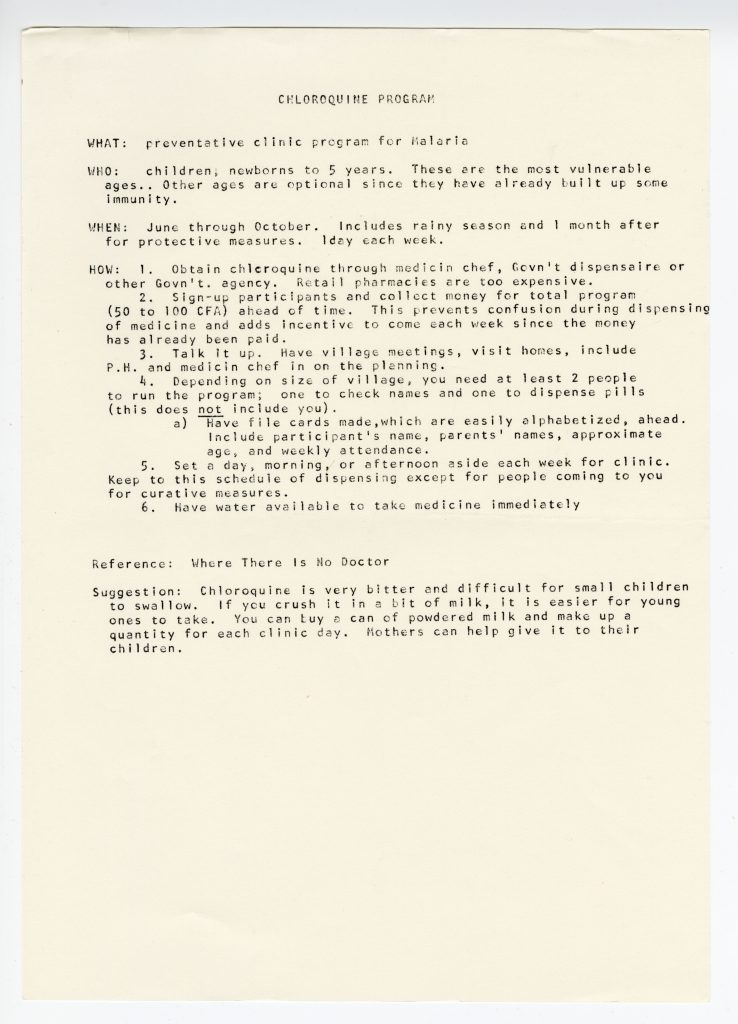

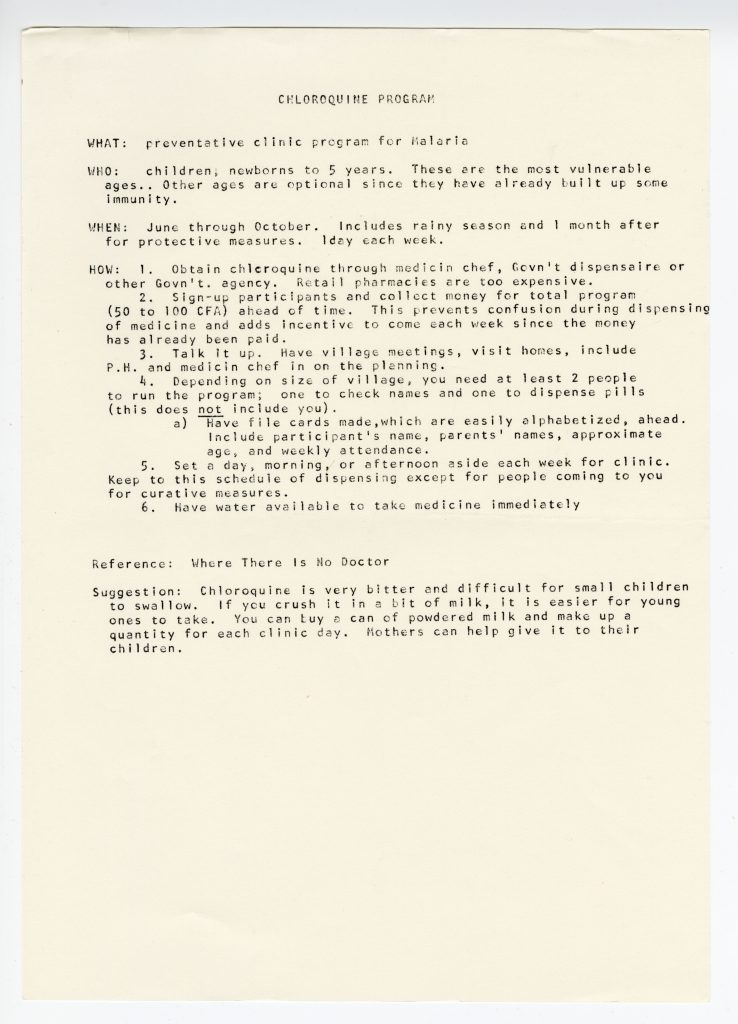

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, for example, were frequently touted by right-wing conspiracy theorists as miracle drugs in the fight against COVID-19. With the benefit of hindsight, and given that credible public health experts have historically warned of the untested efficacy of these drugs, we are now certain that neither chloroquine nor hydroxychloroquine are safe to administer to COVID-19 patients. [7] Records from the Peace Corps Community Archive do show, however, the historical—and empirically proven—use of chloroquine as an antimalarial drug in locales such as Senegal:

Chloroquine Program Document, Shelf: 12.04.02, Box: “Cherie Lockett,” Folder: “Cherie Lockett, Senegal 1979-1981, Health Care N.D.,” Peace Corps Community Archive, American University Library, Washington, D.C.

Yamada grappled with guilt, for although the situation in the United States appeared dire upon her departure from Comoros, her evacuation ensured a better chance of survival:

It came down to privilege. After months of integrating — through language, food and dances — in the end, I am privileged. In a pandemic, I, as an American citizen and Peace Corps Volunteer, got to fly out to a country with better health care.

I could not escape the fact that I was a volunteer that would disappear if things got bad.

People often ask: how will the history of COVID-19 be written? What will history tell us about our response to a global pandemic? Historians and public historians themselves are asking different, more pointed questions: how will we remember our global response to COVID-19? Who gets to shape the memory of the American experience with COVID-19? Is it the historian’s place to weigh the immeasurable suffering and loss of human life against the resilience and moments of unity that will get us through this? Likewise, who and what dictates how Comorians remember COVID-19? What are the stakes if we omit the lived experiences of those who were and are the most vulnerable to COVID-19? Do public historians have a responsibility to interpret/challenge those actors who downplayed and mismanaged the crisis from its outset? For Yamada, her answer is fairly straightforward:

The situation of a country miles away, often labeled as one of the poorest in the world, is very much mirrored here in the United States.

The characteristics of denial, governmental inadequacies and systematic vulnerabilities of certain social groups over others are paralleled. However, one quality is certainly different: we have the resources, and yet, we dared to fail.

[1] Tom Hebert, “Shakespeare and the Ins and Outs of Education Reform,” Peace Corps Writers, n.d., http://www.peacecorpswriters.org/pages/2001/0109/109cllkheb1.html.

[2] Amy Lauren Fairchild, Lawrence O. Gostin, Ronald Bayer, “Contact Tracing’s Long, Turbulent History Holds Lessons for COVID-19,” The Conversation, July 16, 2020, https://theconversation.com/contact-tracings-long-turbulent-history-holds-lessons-for-covid-19-142511

[3] Peace Corps, RPCV Handbook: You’re on your way Home (Office of Third Goal and Returned Volunteer Services, n.d.), 10, https://files.peacecorps.gov/resources/returned/staycon/rpcv_handbook.pdf

[4] World Health Organization, “Questions and Answers on Dengue Vaccines,” Immunization, Vaccines, and Biologicals, April 20, 2018, https://www.who.int/immunization/research/development/dengue_q_and_a/en/

[5] Jody K. Olsen, “Peace Corps Announces Suspension of Volunteer Activities, Evacuations due to COVID-19,” Peace Corps, March 15, 2020, https://www.peacecorps.gov/news/library/peace-corps-announces-suspension-volunteer-activities-evacuations-due-covid-19/

[6] Kako Yamada, “Welcome Home? From Peace Corps Service to COVID-19 America,” Pacific Citizen, May 22, 2020, https://www.pacificcitizen.org/welcome-home-from-peace-corps-service-to-covid-19-america/

[7] United States Food and Drug Administration, “FDA Cautions Against Use of Hydroxychloroquine of Chloroquine for COVID-19 Outside of the Hospital Setting or a Clinical Trial due to Risk of Heart Rhythm Problems,” July 1, 2020, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-cautions-against-use-hydroxychloroquine-or-chloroquine-covid-19-outside-hospital-setting-or