Hi! My name is Emily Messner, and I have spent the past school year as the Peace Corps Community Archive Fellow, cataloging new collections and writing blog posts. As the year ends, I want to share the most unexpectedly remarkable story I encountered in my work. Therefore, this post is a little different because it involves an archival collection and my work to solve a very unique mystery. In the process, I’d also like to give you all a little “peek behind the curtain” to see what it’s like to be a student-archivist. Enjoy!

Chapter 1: Arnold Zeitlin

Of course, this story starts long before me. It begins with a donor-Arnold Zeitlin. In 1961, Arnold Zeitlin was a journalist living in Pittsburgh. He was paying attention to the newly-elected President Kennedy’s policies, especially his implementation of the Peace Corps. Zeitlin then followed in the footsteps of his hero, famed journalist Edward R. Murrow, to work for the government. Additionally, the idea of trading television reviews for service appealed to him. [1] The Peace Corps accepted Zeitlin, and in the summer of 1961, he was on his way to California to take part in a training and selection process.

After a false start, Ghana accepted Arnold Zeitlin as part of the very first Peace Corps group to start their service-Ghana I. He served as an English teacher in Ghana’s capital city, Accra. During his time as a Volunteer, Zeitlin continued writing newspaper articles about his experiences, primarily for Pittsburgh newspapers. Zeitlin’s Peace Corps experience also featured love: he met his wife, got married, and ultimately divorced some years later. After completing his service, Zeitlin resumed his career in journalism, although he also continued to write and think about the Peace Corps. This included one of the first memoirs about Peace Corps Service, To The Peace Corps With Love, which he published in 1965. Recently, Zeitlin donated a great deal of his Peace Corps materials to the Peace Corps Community Archive at American University.

Arnold Zeitlin in Accra with his students, c. 1961-1963. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

Chapter 2: An Archival Puzzle

In November 2022, I had three months under my belt at my fellowship, and I was ready to start processing another collection. I grabbed the box with Arnold Zeitlin’s donations and opened it up to see a great deal of fascinating material. The donation included everything from newspapers, to photos, to correspondence, and much more. I prefer to start working on new collections by processing any correspondence. Letters written before or during a Volunteer’s service usually give me valuable information about the Volunteer and their experiences. This context makes it easier to understand the significance of the rest of their donation. Archivists do their best to preserve the original organization of donations. Sometimes, such as in the case of Zeitlin’s correspondence, the donor only organizes some of their letters. I therefore put the rest of his letters into chronological order.

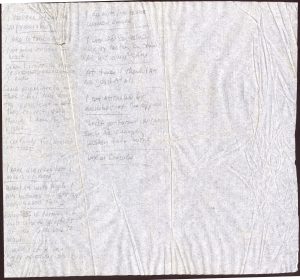

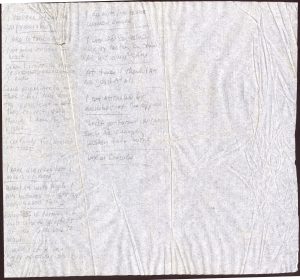

As I was doing this, I found an object that was not a letter at all: this napkin, which had no clear connection to any of the letters I sorted. It had a very strange collection of phrases on it in Zeitlin’s handwriting, such as, “I do not like to see women smoke,” “I wish I could be as happy as others seem to be,” and “I am more sensitive than most.” [2]

What was the story behind this napkin? A full transcript of the letter’s phrases is at the end of the post. Arnold Zeitlin, napkin with list of phrases, 1961, American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

Finds such as this napkin are fairly unusual. In my three years of experience, I have never seen anything quite like this. More delicate paper products such as napkins, especially a completely unfolded one, are not the easiest to write on. Nor are they easy to preserve for several decades. And then there were all the odd phrases, which made no sense and slightly concerned me. As I continued processing the collection, I became more and more confused: What was this object, and what did it mean? Since my position is only a few hours a week, it took me quite a while to process Zeitlin’s collection, and the mystery grew deeper and deeper in my mind.

Chapter 3: Mystery Solved!

The very last set of items that I had to process in Arnold Zeitlin’s collection were a few dozen newspaper articles about Ghana I’s service. Zeitlin wrote about half of them. I began the delicate process of sorting and scanning them- newspaper ages poorly and easily tears. As I started to scan the newspaper articles that Zeitlin wrote during Ghana I’s California training, a few bolded words suddenly leapt out at me. These were the phrases from the napkin!

Mystery solved! Arnold Zeitlin’s newspaper article that included information from the napkin. Arnold Zeitlin, “Peace Corps Quiz Probes Aspirant,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, date unknown. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

After a little more reading, I realized that Zeitlin was writing a humorous, slightly frustrated article about the battery of psychological tests he and fellow hopeful Volunteers had to take. Words on the napkin were quotes from what he considered the most ridiculous true/false psychological questions on a test. [3] In To the Peace Corps With Love, which I would read later, Zeitlin discussed enduring the wide range of psychological tests and interviews, alongside his equally humored and incredulous peers. His conclusion was that the Peace Corps was bending over backwards to make sure that this first group of Volunteers would carry out their work as smoothly as possible. [4] He also noted that one of the psychologists, Brewster Smith, had not taken kindly to his critical article on the matter. Even as he hurried to join the rest of Ghana I after their arrival, his send-off included a good-natured, exasperated warning to write no further articles about psychiatrists. [5]

To confirm my findings, I contacted Arnold Zeitlin himself, who graciously answered my list of questions about a small occurrence that had happened more than sixty years before. To supplement the memoir, Zeitlin noted that he thought that the Peace Corps’ reliance on all of the odd tests to predict Volunteers’ performance was “absurd.” [6] He found the situation so ridiculous that he had to write an article. Zeitlin enjoyed the opportunity to share his experiences-whether fascinating or ridiculous- with his readers back in Pittsburgh. [7] Finally, Zeitlin wrote that he had been able to become friends with Brewster Smith years later over a lunch in Hong Kong, where Zeitlin was living at the time. [8] With all of this information, the ends of my napkin mystery tied themselves in a surprisingly neat bow. You can see the results in the finding aid for Zeitlin’s collection, which includes an entry just for the napkin. Zeitlin recently passed away, after a long, rich life. I am very grateful for the time he took to tell me about his experiences.

Arnold Zeitlin with his wife, celebrating his ninetieth birthday. Photo from Arnold Zeitlin.

Epilogue: The Mysteries Continue

This is not the only mystery that I have focused on this year. For example, one of my first blog posts was on a mystery novel inspired by the author’s lived experiences in the Peace Corps. And while this “case” was a more involved puzzle than most of my work entails, mini-mysteries are not uncommon while working in archives. If part of a donation comes without enough context through the materials surrounding it, it becomes a little mystery of its own. That is fine by me! Figuring out more information about these items is one of my favorite parts of this wonderful job. On that note, I am very excited to say that I will be back again as the fellow for the 2023-2024 school year. So be on the lookout for more Peace Corps mysteries and intrigues that I uncover in my work, starting in August!

Transcription of the napkin’s phrases:

- I like to flirt

- I believe my sins are unpardonable

- I like to talk about sex

- I am more sensitive than most

- Often I cross the street in order not to meet someone I know

- Some people are so bossy that I feel like doing the opposite of what they request, even though I know they are right

- I certainly feel useless at times

- I have diarrhea once a month or more

- When I am with people, I am bothered by hearing very queer things

- Everything is turning out just like the prophets of the Bible said it would

- I wish I could be as happy as others seem to be

- I do not like to see women smoke

- I would certainly enjoy besting a [crude?] at his own game

- At times I think I am no good at all

- I am attracted by members of the opp[osite] sex

- Christ performed miracles such as changing water into wine

- WX or Lincoln

[1] Arnold Zeitlin, email message to author, February 7, 2023; Arnold Zeitlin, To the Peace Corps With Love (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965), 19.

[2] Arnold Zeitlin, napkin with list of phrases, 1961, American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[3] Arnold Zeitlin, “Peace Corps Quiz Probes Aspirant,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, date unknown. American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[4] Arnold Zeitlin, email message to author, February 7, 2023; Arnold Zeitlin, email message to author, February 7, 2023.

[5] Zeitlin, To the Peace Corps With Love, 48.

[6] Arnold Zeitlin, email message to author, February 7, 2023.

[7] Arnold Zeitlin, email message to author, February 7, 2023; Arnold Zeitlin, email message to author, February 7, 2023.

[8] Arnold Zeitlin, email message to author, February 10, 2023.