Before leaving for a foreign country, Peace Corps Volunteers in the 1960s were required to complete intensive training to help prepare them for their experiences abroad. This training occurred at universities all over the United States. They learned a variety of tasks ranging from agriculture and livestock care to language studies. Each PCVs’ training varied by where they attended training, their service type, and other factors.

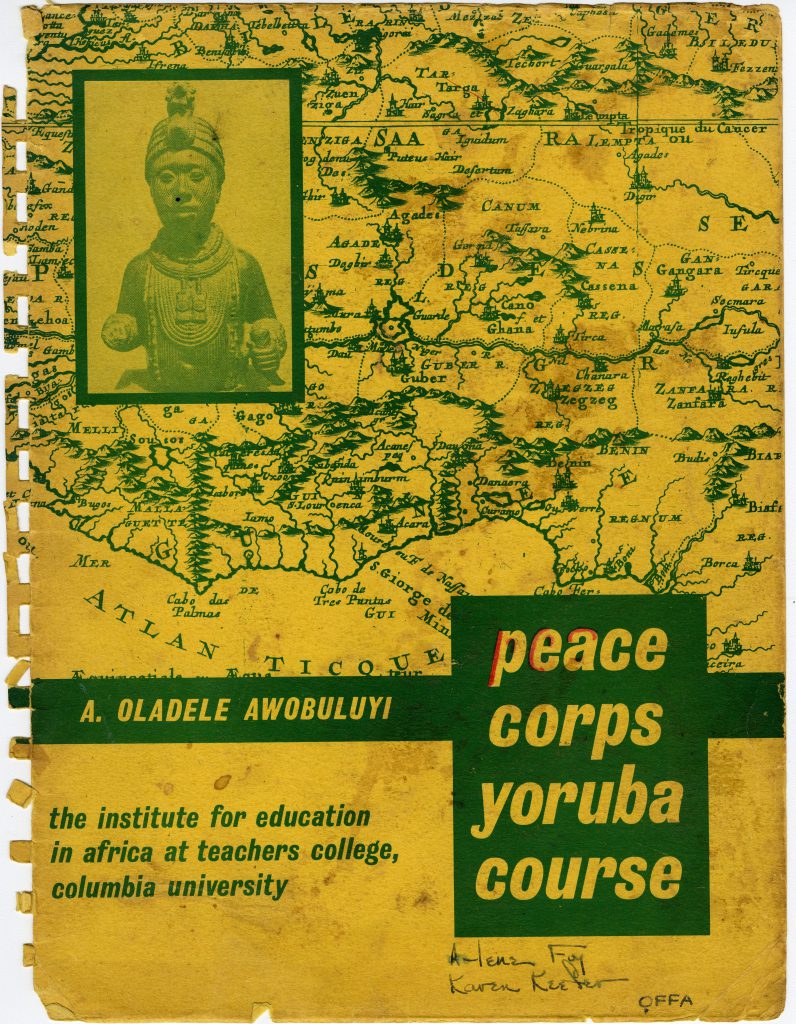

Peace Corps Volunteers all received informational packets on their training, much like this one from Karen Keefer who trained at Columbia University for her service in education in Nigeria.

One of the earlier PCVs is Thomas Hebert, who trained at University of California, Los Angeles in June of 1962. Hebert served in Nigeria from 1962 to 1964 educating youth and managing the University of Ibadan’s Shakespeare Traveling Theatre program. Hebert spent a total of 419 hours training for his service in Africa. The bulk of his training program was an orientation on Africa and Nigeria, totaling 92 hours, where he learned how to effectively communicate and understand the culture he would be serving in. Interestingly enough, Hebert also had a total of 81 hours of training in American Civilization and Institutions, which would “[enable] the volunteers to see political events more perceptively, to view the interchange of political interests more realistically, and to articulate democratic values more convincingly,” according to the training informational packet.

Hebert also spent 60 hours learning educational practices for Nigeria, in order to understand how to effectively reach his students abroad. He also had 55 hours of training in the languages of Hausa, Ibo, and Yoruba, the three major indigenous languages of Nigeria. In addition to his practical training, Hebert also spent 43 hours on health training and 56 hours in physical education. The Peace Corps emphasized the importance of each PCV’s health during their service. Lastly, he also spent 32 hours on “Special Features,” which ranged from lectures to documentaries.

Winifred Boge attended training at University of California, Davis from February to May 1965. The program totaled 720 hours of work over a 12-week period, resulting in an average of 60 hours per week. Boge served on the Health Nutrition Project in India, but her training also covered a variety of topics to assist with her transition into life in a different country.

For Boge, the most time was spent on language training, with a total of 300 hours on learning Telugu. Next, she focused on technical studies on health and nutrition, for a total of 200 hours. Following this, she also learned area studies and world affairs for 105 hours in order to understand the history and culture of her place of service. Also required for training was physical education as well as health and hygiene to ensure the health of every PCV.

One of the more interesting areas of study is the topic of Communism for 15 hours total. While each area of study in the information packet includes a description and list of teachers, Communism lacks this information. Even though the Red Scare of the 1950s had passed, the Peace Corps probably wanted to prepare their PCVs for different types of government in the world.

Many Volunteers enjoyed their training because it gave them a chance to get to know fellow PCVs. Pictured here by Boge, PCVs interact during their training at UC Davis.

Peggy Gleeson Wyllie trained at Brooklyn College from 1963-1964 for her time as a nurse in Colombia. She spent most of her time–a total of 360 hours–in intensive language studies in Spanish. Not surprisingly, the second highest element of training at 106 hours was technical studies, along with 30 hours of health education. Technical studies included techniques in Nursing as well as the prevention and treatment of diseases found in Colombia. Wyllie also spent 72 hours learning the history and culture of Colombia, as well as 60 hours studying American studies, world affairs, and Communism. Like Boge, Wyllie learned “critical appraisal of the developing concepts and organizational challenges of the Communist world.” Lastly, she attended classes in physical training for 72 hours and a general “Peace Corps Orientation” for 20 hours.

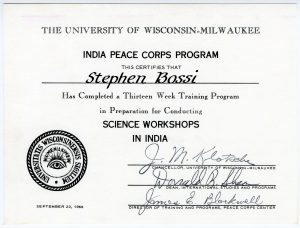

After completion of their training, many PCVs received a certificate like this one. Steve Bossi completed his training in conducting Science Workshops in India from University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Each training session, no matter how different in terms of location of training, location of service, or service type, served to best prepare each PCV for the challenges and successes they experienced during their service. Training takes into account the culture and society each PCV is entering in order to provide guidance for the most effective approaches to help both the Volunteer and community alike.