What makes a good Peace Corps volunteer? Is it experience and compassion, leadership or flexibility? Or, is it confidence? What does it mean to be a Peace Corps volunteer, and what do we expect to gain from volunteering abroad? These were the questions that Peace Corps officials mulled over as they prepared a special training program directed at young Native American volunteers.

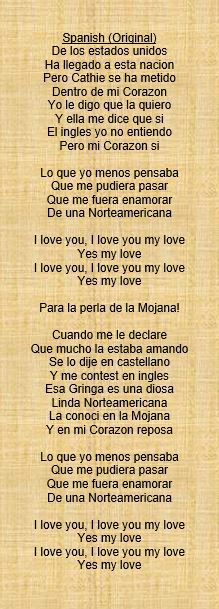

LaDonna Harris in 1976. (2012.201.B0250.0666, photo by P. Southerland, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

Developing the Program

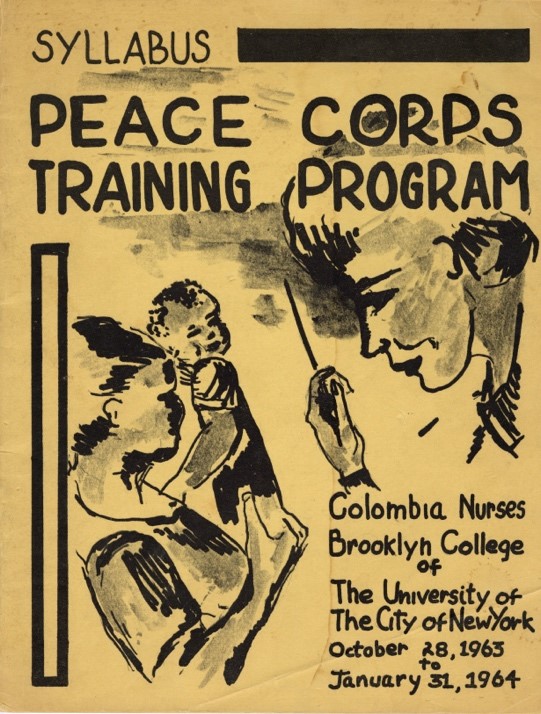

“Project Peace Pipe” was created in 1966, as a collaborative program between the Peace Corps and a Native-led organization called Oklahomans for Indian Opportunity (OIO). The project specifically recruited and trained Indigenous adults for service in the Peace Corps, following OIO’s mission to improve the lives of American Indians by offering programs for community development, work experience and placement, and youth activities.[1] Comanche political activist and OIO founder LaDonna Vita Tabbytite Harris hoped that Peace Corps service would help the volunteers develop “talents for organization and skill in mobilizing community action…applicable to the problems of Indian communities in all parts of the United States where skilled Indian leadership is needed, but often unavailable.”[2] Not only would these volunteers return with practical skills, OIO envisioned that American Indian RPCVs would have greater opportunity to work in federal agencies and provide healthy role models for other Indigenous youths.

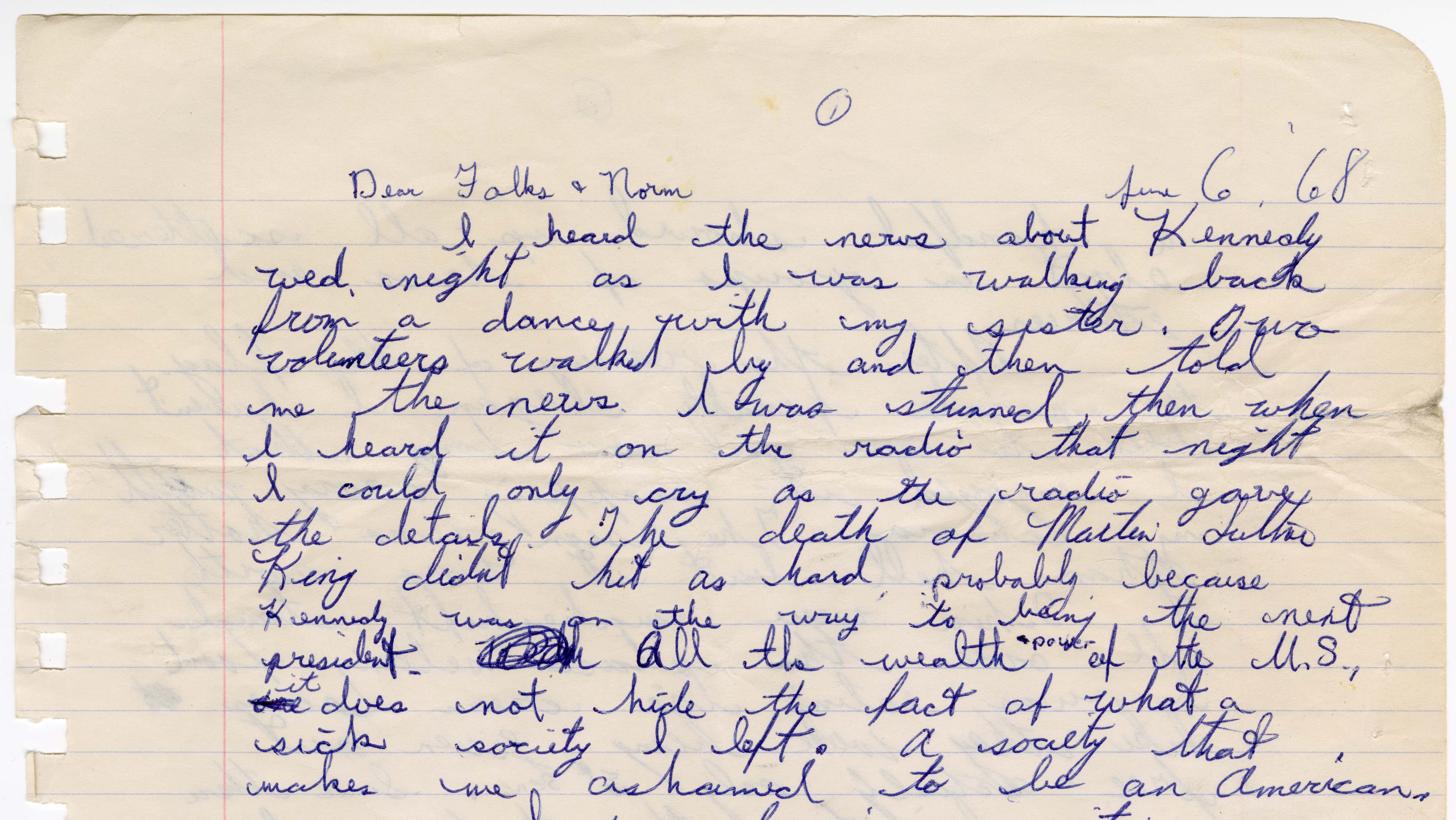

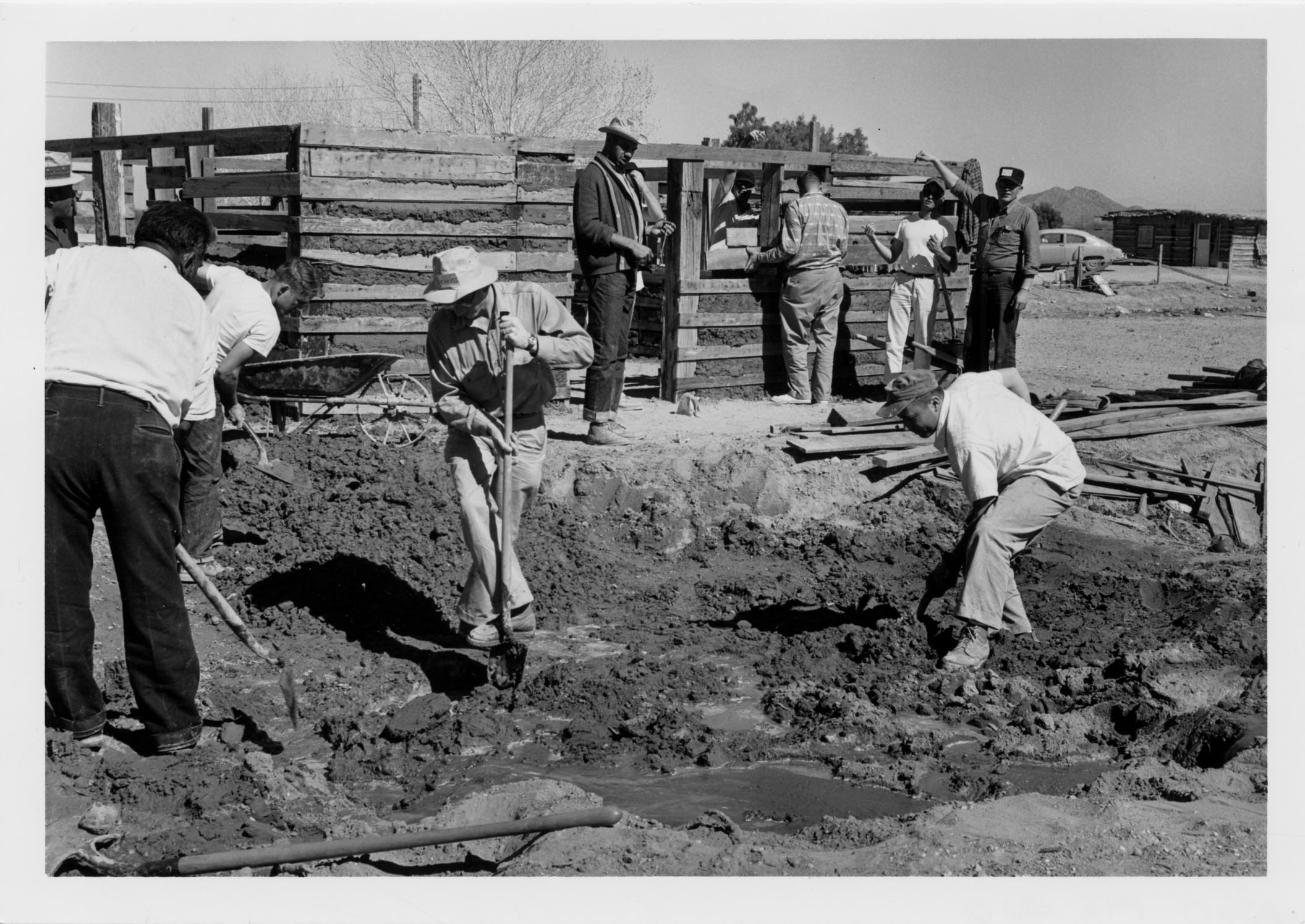

Donald Broadwell, Peace Corps Escondido, Summer 1968. Colombia Rural Community Development Group B, August 28-October 14, 1968.

Donald Broadwell, a PCV recruited through this program, also believed that the project operated under the assumption that Native Americans would have a greater ability to understand with the life experiences and bond with rural Colombians, many of whom were subsistence farmers with strong Mayan backgrounds.

As for the Peace Corps, the project was one of the first attempts to attract volunteers with working-class and marginalized backgrounds. Although the Peace Corps sought to emphasize “self-reliance, racial equality, the right to self-determination, and social justice,” the organization struggled to attract volunteers of color.[3] An article in the Journal of Black Studies reported that in the 1960s, most Black youths considered the Peace Corps to be “an agency for White, middle-class Americans.” While service was possible to many white, middle-class individuals fresh out of college, many people of color and working-class graduates took jobs to support their families or sought to improve their own communities. [4]

Peace Corps officials used the interest in Project Peace Pipe to counter this WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) image and attempted to create more accessible avenues for “socio-economically deprived minority group youngsters.”[5] While there are no available records that mention the origin of the project’s name, the use of the term “peace pipe” traces back to the arrival of European colonists, who applied the term to Indigenous ceremonial pipes.[6] It is likely that the name “Project Peace Pipe” may have just been the result of the Peace Corps’ desire for “peace” imagery, and the irony was not lost on volunteers.

In an article in the August 1968 issue of the Peace Corps Colombia monthly newsletter, Porvenir, one editor commented:

“Regardless of the appropriateness of this name, it is curious that a program, intended to integrate, labels the group in question with a title that differentiates them. Names serve to categorize and tell things apart; why make a distinction when the intent is to show the similarity of different Americans when working toward a common end? Even if the title “Operation Peace Pipe” proved useful in training and recruiting, that should be the extent of its function.”

The unique title was not the only difference that set the group apart from the other volunteers. The OIO and Peace Corps officials designed the program around the idea that Native youths, “because of their lack of self-confidence, felt they had little to contribute to persons overseas.” Working under this assumption, the program designed targeted recruitment processes and a five week pre-training to build confidence and develop communication skills.

Peace Corps-Indigenous Relationships and Red Power

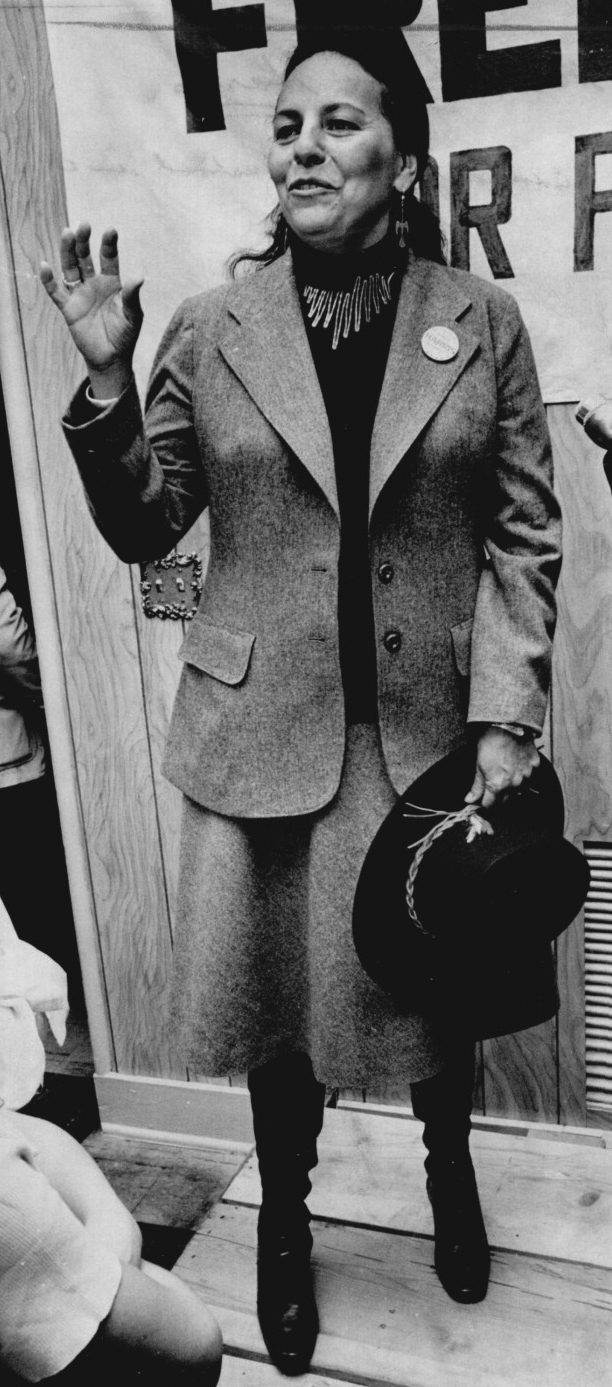

Project Peace Pipe was not the first interaction Native communities had with the Peace Corps. In fact, impoverished conditions on reservations were so similar to underdeveloped areas in Latin America, Africa, and Asia that the Peace Corps used them for preliminary community development training. In at least one instance, in 1962 volunteers stationed at the University of Arizona prepared for service at Gila River Reservations in Arizona. The Peace Corps Volunteer reported other development programs at the Navajo Reservation in New Mexico. [7]

Peace Corps Volunteers during training at the Gila River Reservation in Arizona. 1962. University Archives Photographs, Arizona State University Library.

The Project also coincided with the rise of the Red Power movement. Across the country, Native Americans mobilized to protest and rewrite the history of American Indigenous peoples, address high levels of poverty, and bring legal suits against states stealing Indian land and violating federal treaties.[8] During the 1960s, communities formed organizations like the National Indian Youth Council (NYIC) and the American Indian Movement (AIM), leading groups to Washington, D.C. to occupy the offices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, called the “Trail of Broken Treaties.”

In fact, three volunteers recruited through Project Peace Pipe were Sioux members from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where the town of Wounded Knee is located. Growing up in Pine Ridge, these volunteers were likely influenced by the violent confrontations between white supremacists and their community, and the increased political militancy of the organized Red Power movement. If the volunteers returned after their service in 1970, they could have been involved with the AIM occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973; however, no available records mention this. To learn more about the history of Wounded Knee, visit Democracy Now and the History Channel.

Pine Ridge Sign, October 17, 2016. posted to Flickr Creative Commons by Orientalizing.

So why did a Native-led organization like Oklahomans for Indian Opportunity join forces with a federal agency at the height of the Red Power movement? The answer lies with activist LaDonna Vita Tabbytite Harris. Harris founded OIO after Oklahomans elected her husband Fred Harris to the Senate. After her family relocated to Washington, D.C., Harris loudly advocated for Native rights and legislation, including championing the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act. Her determination and husband’s political networks put her in a place to help Indigenous communities gain federal recognition and push for change. Seeing an opportunity for youth engagement, Harris instigated a partnership with Peace Corps and established authority over the program design from the onset.

Moving Forward

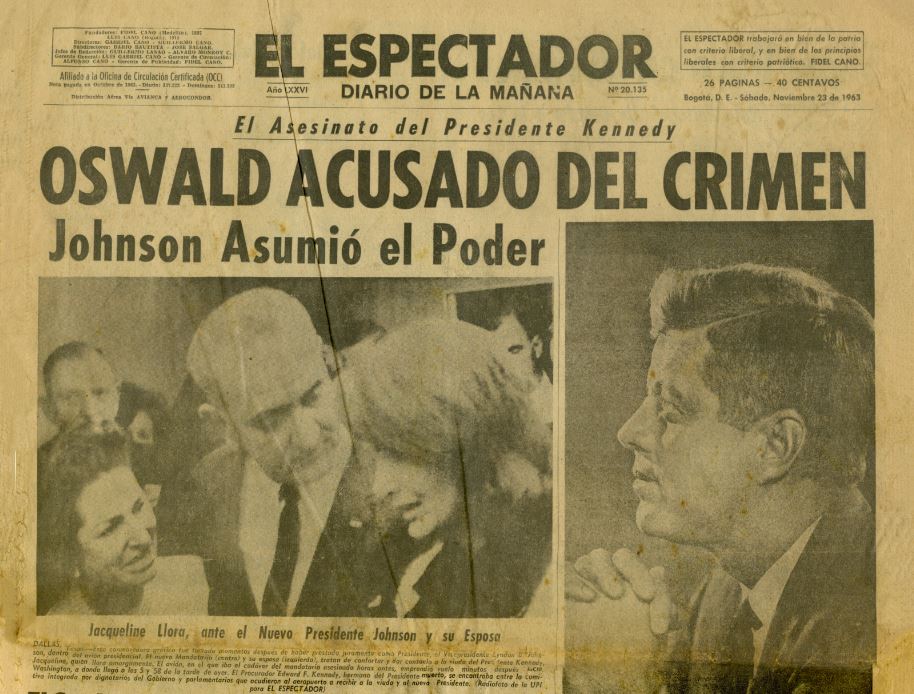

Only 5 years prior, President Kennedy announced to the nation, “ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country,” before establishing the Peace Corps. Project Peace Pipe also considered what Peace Corps could do for Indigenous youths. But how did the actual volunteers compare with the judgments made by OIO and the Peace Corps?

Project Peace Pipe Part 2 will explore the practical aspects of specialized training, the experiences of volunteers, and the outcome of the program following the merge into the rest of Peace Corps Colombia- Rural Community Development-B.

References:

Amin, Julius A. “The Peace Corps and the Struggle for African American Equality.” Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 29, No.6, July 1999, 817. (Accessed January 22, 2019) https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2645886.pdf

Chavez, Aliyah, “LaDonna Harris ‘stumbled’ into a legacy of impact,” Indian Country Today. August 18, 2019.

Harris, Mrs. Fred R. and Leon H. Ginsberg, “Project Peace Pipe:Indian Youth Pre-Trained for Peace Corps Duty”, Journal of American Indian Education, Vol. 7 No. 2, January 1968

Moore, Powell A. (1959). The Calumet Region: Indiana’s Last Frontier. Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

Old Elk, Hunter “127th Remembrance of the Wounded Knee Massacre,” Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Decmber 29, 2016. (Accessed January 27, 2020) https://centerofthewest.org/tag/wounded-knee/

Peace Corps Division of Volunteer Support, The Peace Corps Volunteer, a Quarterly Statistical Summary, (Columbia University: The Division, 1962), 13. https://books.google.com/books?id=mIOKCxx-scUC&pg=RA16-PA13&lpg=RA16-PA13&dq=peace+corps+training+on+indian+reservations&source=bl&ots=grUjRQ3-TY&sig=ACfU3U1fOyhvcjnt_zwg5KA-EumuUzxTaA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwie_rKY7YXnAhWQq1kKHRbRBUMQ6AEwEnoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=%20indian%20reservations&f=false

Peltier, Leonard “Wounded Knee II, 30 Years Later,” Democracy Now, May 9, 2003. (Accessed January 27, 2020) https://www.democracynow.org/2003/5/9/wounded_knee_ii_30_years_later

“The Native American Power Movement,” Digital History, 2019. (Accessed January 27, 2020) http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3348

“Wounded Knee,” History, November 6, 2009. (Accessed January 27, 2020) https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/wounded-knee

[1] Mrs. Fred R. Harris and Leon H. Ginsberg, “Project Peace Pipe:Indian Youth Pre-Trained for Peace Corps Duty”, Journal of American Indian Education, Vol. 7 No. 2, January 1968, 22.

[2] She left OIO in 1968 after President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed her to the National Council on Indian Opportunity (NCIO), but the organization’s inaction led her to resign and continue grassroots activism. Mrs. Fred R. Harris and Leon H. Ginsberg, “Project Peace Pipe:Indian Youth Pre-Trained for Peace Corps Duty”, Journal of American Indian Education, Vol. 7 No. 2, January 1968, 21.

[3] Julius A. Amin, “The Peace Corps and the Struggle for African American Equality.” Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 29, No.6, July 1999, 811. (Accessed January 22, 2019) https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2645886.pdf

[4] Julius A. Amin, “The Peace Corps and the Struggle for African American Equality.” Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 29, No.6, July 1999, 817. (Accessed January 22, 2019) https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2645886.pdf Marshall, M. (1984, October). The Peace Corps: Alive and well, and looking for Blacks. Ebony Magazine, pp. 48-54.

[5] Mrs. Fred R. Harris and Leon H. Ginsberg, “Project Peace Pipe:Indian Youth Pre-Trained for Peace Corps Duty”, Journal of American Indian Education, Vol. 7 No. 2, January 1968, 22.

[6] Moore, Powell A. (1959). The Calumet Region: Indiana’s Last Frontier. Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

[7] Peace Corps Division of Volunteer Support, The Peace Corps Volunteer, a Quarterly Statistical Summary, (Columbia University: The Division, 1962), 13. https://books.google.com/books?id=mIOKCxx-scUC&pg=RA16-PA13&lpg=RA16-PA13&dq=peace+corps+training+on+indian+reservations&source=bl&ots=grUjRQ3-TY&sig=ACfU3U1fOyhvcjnt_zwg5KA-EumuUzxTaA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwie_rKY7YXnAhWQq1kKHRbRBUMQ6AEwEnoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=%20indian%20reservations&f=false

[8] “The Native American Power Movement,” Digital History, 2019. (Accessed January 27, 2020) http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3348