In 1965, the United States expanded its role in South Vietnam into full-fledged combat. [1] By the time that the United States withdrew its troops in 1973, the country had divided between the conflict’s supporters and those who opposed it. During the war, a significant number of Peace Corps Volunteers were among this opposition. The war would impact their experience with the Peace Corps, as well as the organization itself. Two of the main ways that the Vietnam War impacted the Peace Corps and its Volunteers were through the draft and Volunteers’ various acts of protest.

The Peace Corps and the Vietnam War Draft

One of the main ways that the Vietnam War impacted the Peace Corps and its Volunteers was through the draft. Starting in 1964, the United States expanded its peacetime draft to provide soldiers for its escalating conflict. [2] As the U.S. presence in Vietnam increased, the draft would impact the Peace Corps in two key ways. First, men eligible for the draft increasingly utilized the Peace Corps as a way to avoid military service if they were opposed to the war. This avoidance took multiple forms. For example, Dan Krummes, who volunteered in Senegal between 1972 and 1974, received Conscientious Objector status. As a part of maintaining this status, he was required to do community service. The Peace Corps was an option for fulfilling the requirement, which he chose. [3]

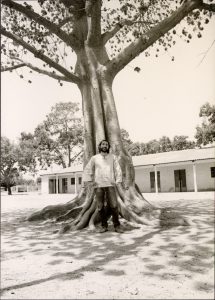

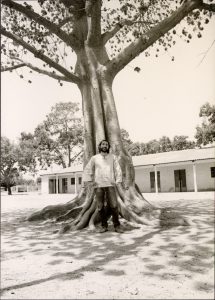

Dan Krummes outside the school where he taught in Senegal in 1973.

Another route many draft-eligible men took was to quietly apply for the Peace Corps without Conscientious Objector status and not state their true intentions, since the Peace Corps was in the process of strongly pushing back against accusations that the organization was full of “draft dodgers.” [4] For instance, Guatemala Group XI, which served between 1968 and 1970 at the height of the Vietnam War, had several members who mentioned years later that they joined to avoid the conflict. Peter Shack, for example, had completed law school and could no longer avoid the draft through continuing his education. Therefore, he applied to both the Peace Corps and the Foreign Service, choosing the Peace Corps when he was accepted to both. [5]

Second, a controversy erupted between the Peace Corps and the military over the deferred status of Peace Corps Volunteers. Draft-eligible men who were serving in the Peace Corps, no matter their opinion of the war, joined because they thought that they would be able to receive a deferment from the draft in order to serve their full two-year term. The Peace Corps secured this arrangement during its creation in 1961, as the government deemed their work to be in the national interest. However, as the war continued, multiple male Volunteers received notice of being drafted while serving. A handful of local draft boards chose not to grant the deferment, forcing the Volunteers to end their service early and report back to the United States. [6]

One of these incidents occurred in Honduras, where the affected Volunteer group was so incensed that five members wrote to the Peace Corps Volunteer, a magazine for Volunteers. The publication featured their joint letter in its November 1967 issue. Four members of the Honduras group had received word that they were in the process of being called for military service from their draft boards, despite appeals from Peace Corps staff. The authors (three men and two women) included in their arguments that the process of removing Volunteers in the middle of their work could only be detrimental to the relationship between the United States and host countries. In addition, such incidents showed that the United States was a country much more supportive of war than peace. [7]

The Peace Corps began to take a more active role in working with Volunteers to help them continue their service, with director Jack Vaughn announcing that he would even be writing letters of recommendation for Volunteers who sometimes needed to convince not only their local board but the State and Presidential Appeal Boards as well. [8] The organization also refused to accept the Volunteers most likely to be drafted who had not already received a deferment. These strategies would help to alleviate the issue. [9] However, discussions of the complicated relationship between the Peace Corps and draft boards continued to feature in the Peace Corps Volunteer through November 1969.

Protesting Volunteers

The Vietnam War also impacted the Peace Corps and its members when Volunteers around the world began to protest the conflict, forcing the Peace Corps, a government organization, to respond. A notable example is that of Volunteer Bruce Murray. In 1967, he wrote a letter to the New York Times protesting the war during his service in Chile, which the newspaper did not publish. Murray, who was serving in Chile, sent it to a local paper, which did publish it. At that, the Peace Corps terminated his service without giving him an opportunity to contest it and sent him home. Once there, his local board drafted him and denied his application for Conscientious Objector status, despite the fact that he had a deferment. He then sued the Peace Corps over the incident, winning in December 1969. [10]

After this very public fiasco began, the Peace Corps relented but was still much more likely to tolerate intergroup forms of protest. The organization tried to strike a balancing act between Volunteers’ freedom of speech and the Peace Corps’ preferred apolitical stance for Volunteers. For example, Jeff Fletcher, who volunteered in Bolivia, was a regional editor for the Pues magazine, written by Bolivia Volunteers for their peers. The February-March 1969 issue included multiple articles stating clear opposition to the Vietnam War. This included a work of satire suggesting that the United States replace its current troops with mercenary armies and bounty hunters before arguing that all war should end. [11] However, the authors and editors of Pues, and other Volunteers creating similar anti-war media, were not subject to punishment from the Peace Corps.

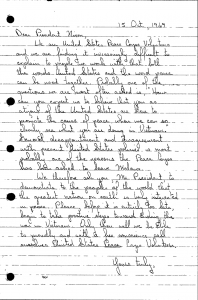

A form of protest that went very smoothly for both Volunteers and the Peace Corps was the participation of Volunteers around the world in the Moratorium Day protests of October 15, 1969. On that day, over two million Americans across the country assembled in opposition to the war. [12] Protesting Volunteers included Bob and Susan Irwin, who were serving in Malawi at the time. They wrote a letter to President Nixon, describing the difficulty they had as Peace Corps members representing a country that was demonstrating much greater interest in war than in peaceful international service. [13] Richard Nixon’s presidential administration chose to push back against Americans’ protests as a whole. However, Peace Corps Director Joe Blatchford neither punished Volunteers nor changed the organization’s stance on protest or the Vietnam War. [14]

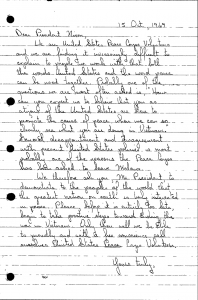

The Moratorium Day letter written by the Andersons.

Some group protests among Volunteers caused other types of difficulties for the Peace Corps, especially if they happened in a more public or internationally-facing way. One example of this was the brief Volunteer protest outside the U.S. Embassy in Afghanistan upon the occasion of Vice President Spiro Agnew’s January 6, 1970 visit. Designed by the Volunteers in such a way to register their dissent while not creating an international incident, the American media nevertheless heavily covered the protest in connection to local Afghan demonstrations. Members of the media included Arnold Zeitlin, a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer now working for the Associated Press, who wrote an article about the incident. [15] This led to the Peace Corps having to respond to national pushback against the incident and defend the Volunteers under scrutiny. However, the initial action only took place because the Volunteers had explicitly worked to make their protest small and only directed towards Agnew. Volunteer protest against the Vietnam War, and the Peace Corps’ various reactions to it, would have a defining impact on the organization until the end of the war.

The consequences of the United States’ military involvement in Vietnam very much extended to the Peace Corps. During the conflict, a significant number of Peace Corps Volunteers joined the Americans opposed to the war, but the war would also impact all Volunteers and the organization as a whole. Two central ways that the Vietnam War impacted the Peace Corps were in relationship to the draft and opposing Volunteers’ various forms of anti-war protest.

[1] “Overview of the Vietnam War,” Digital History, University of Houston, 2021, https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraid=18&smtid=1.

[2] “The Military Draft During the Vietnam War,” Resistance and Revolution: The Anti-Vietnam War Movement at the University of Michigan, 1965-1972, Michigan in the World, accessed December 14, 2022, https://michiganintheworld.history.lsa.umich.edu/antivietnamwar/exhibits/show/exhibit/draft_protests/the-military-draft-during-the-.

[3] Douglas S. Brookes, “Daniel S. Krummes: A Brief Biography,” Unpublished biographical note, American University Archives, Washington, D.C.

[4] Molly Geidel, “Ambiguous Liberation: The Vietnam War and the Committee of Returned Volunteers,” in Peace Corps Fantasies: How Development Shaped the Global Sixties, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 160-162. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt16ptn2s.8.

[5] Shack, Peter. Interview by Douglas Noble. Peter Shack.mp4†, TheirStory, American University Special Collections, https://theirstory.io/stories/6193d32472f16a0005b5d9f7/author/. Accessed 14 December 2022.

[6] “A Look At PCVs Who Face the Draft,” Peace Corps Volunteer, Vol. 7 No. 4 (March 1969), 20, American University Archives, Washington, D.C., https://dra.american.edu/islandora/object/peacecorps%3A2348.

[7] Summary from Romania Green, et al, Letter to the Peace Corps Volunteer, Peace Corps Volunteer, Vol. 6 No. 1 (November 1967), 21. American University Archives, Washington, D.C., https://dra.american.edu/islandora/object/peacecorps%3A2334.

[8] “Peace Corps to intervene for Volunteers Seeking Deferments,” Peace Corps Volunteer, Vol. 7 No. 2 (December 1967), 24, American University Archives, Washington, D.C., https://dra.american.edu/islandora/object/peacecorps%3A2335.

[9] “PCVs Who Face the Draft,” 21.

[10] Summary from “The Bruce Murray Case,” Peace Corps Volunteer, Vol. 8 No. 3/4 (March-April 1970), 11, American University Archives, Washington, D.C., https://dra.american.edu/islandora/object/peacecorps%3A2359.

[11] Mickey McGuire, “A Modest Proposal,” Pues No. 3 (February-March 1969), 3. American University Archives, Washington, D.C., https://auislandora.wrlc.org/islandora/object/peacecorps%3A3156.

[12] “Moratorium Day: The day that millions of Americans marched,” BBC News, 15 October 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-49893239.

[13] Bill Irwin and Susan Anderson to Richard Nixon, 15 October 1969, copy of letter, American University Archives, Washington, D.C. In response, they received a form letter and packet describing the reasons why the United States was fighting in Vietnam.

[14] “Volunteers Join Moratorium with Petitions, Vigils,” Peace Corps Volunteer Vol. 7 No. 13 (December 1969), 2-3. American University Archives, Washington, D.C. https://dra.american.edu/islandora/object/peacecorps%3A2357.

[15] Summary from, “Protest in Afghanistan (A Case Study),” Peace Corps Volunteer, Vol. 8 No. 3/4 (March-April 1970), 13, 22. American University Archives, Washington, D.C., https://dra.american.edu/islandora/object/peacecorps%3A2359. Outside of a quote included in the Peace Corps Volunteer, a copy of Zeitlin’s article could not be located. Correspondence and mementos from Zeitlin’s service in Ghana from 1961-1963 are also in the Peace Corps Community Archive.