Every volunteer watches as the world at home continues while they are abroad. Some changes are personal, such as the birth of a nephew or the death of a loved one. Other events are huge—where the entire country laments at the news of a disaster.

Thousands of miles away, Peace Corps Volunteers received news that shook the nation, and even the world. Radios broadcast the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and his brother Senator Robert Kennedy, the destruction of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, and the deadly attacks on September 11, 2001. While distance can lend space to heal from tragedy, it also cuts PCVs off from important support systems.

These six volunteers watched American events unfold from the non-military, external broadcasting program Voice of America, newspapers, and letters from their families and friends. They reflected on national elections, assassinations, and devastating disasters—often remarking on their isolation and questioning their faith in humanity.

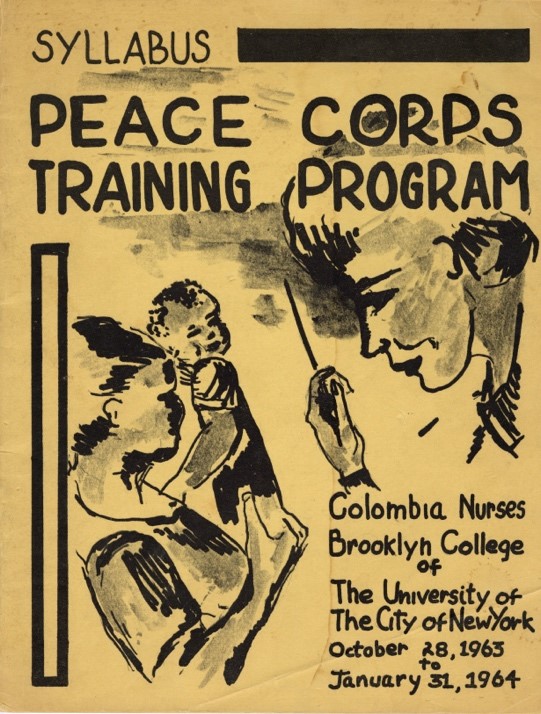

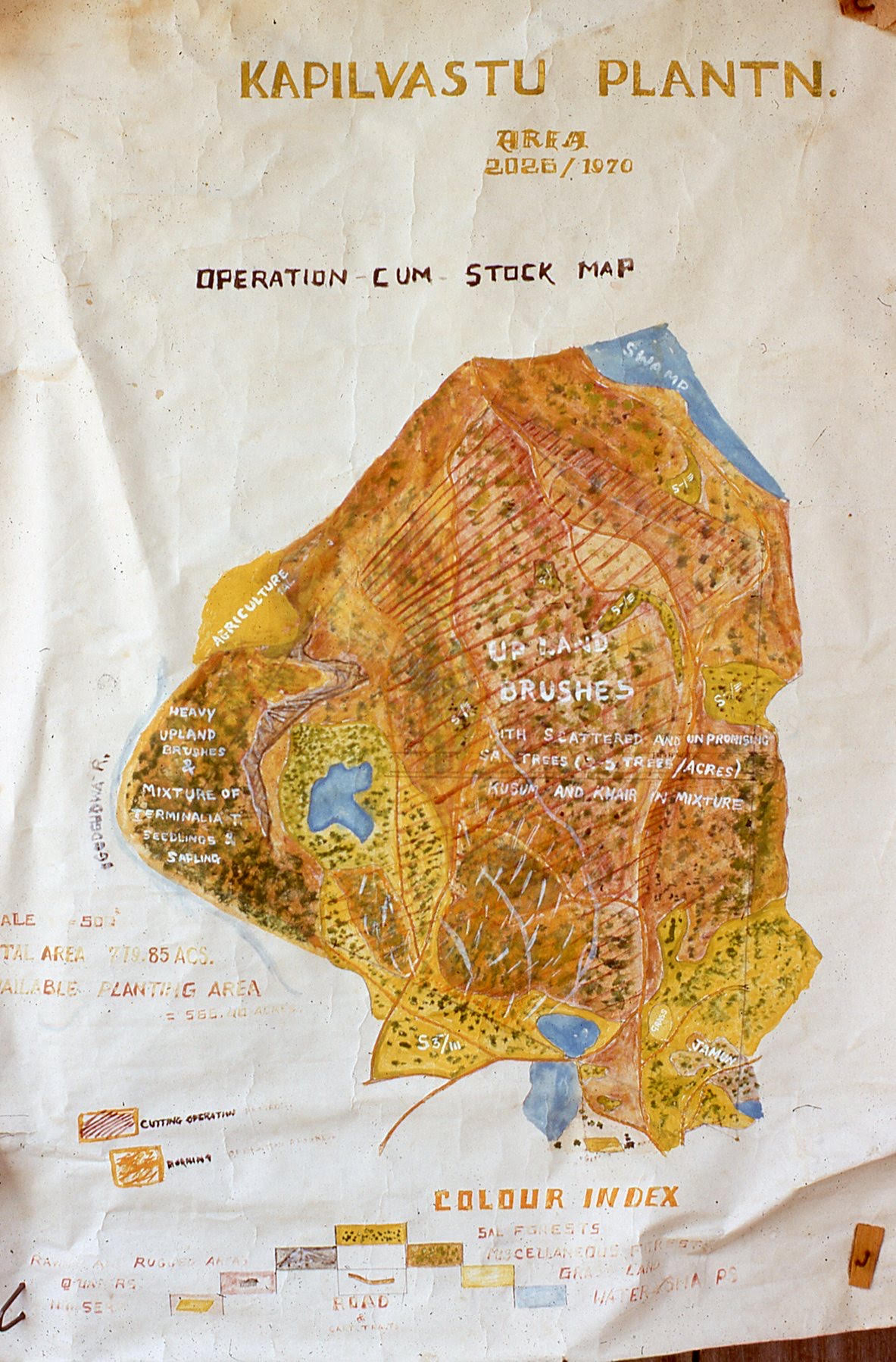

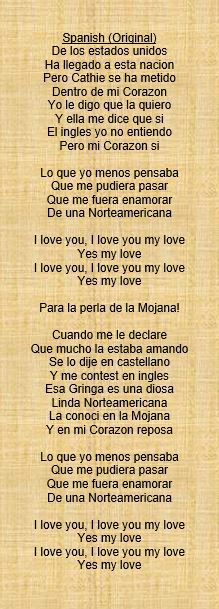

“I don’t see much in the future.” Assassination of John F. Kennedy- November 22, 1963

Headline in Colombian Newspaper on November 23, 1963. Friends of Colombia Collection, Peace Corps Community Archives.

Geer Wilcox learned about the assassination of John F. Kennedy’s while living in the Dominican Republic. As a blind Peace Corps Volunteer, Wilcox relied on hearing the news from neighbors reading newspapers and the radio. He often commented on the state of American politics or the Vietnam War as he listened to the international news broadcast, the Voice of America. When the news of Kennedy’s death broke, Wilcox reported feeling apprehensive of Lyndon Johnson and the future.

Wilcox expresses his shock in a recorded letter home to his parents on November 30, 1963:

Rene Cardenas was in Colombia when the news broke. She processes the aftermath of Kennedy’s death in a poem titled “Yesterday November.”

The address for sorrow

two inches away

the president has been killed

the clouds of wet season

the earth’s longest pity

everything is split time

a piece of wood

pulled apart at the grain

in an apartment in Cucuta

han asesinado a Kennedy

bells toll for three days

sent notes of condolences

to the wall

by my bed

two inches away

from my face.

Additional reactions to President Kennedy’s death are recorded here.

“What a sick society I left.” Assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy- June 6, 1968

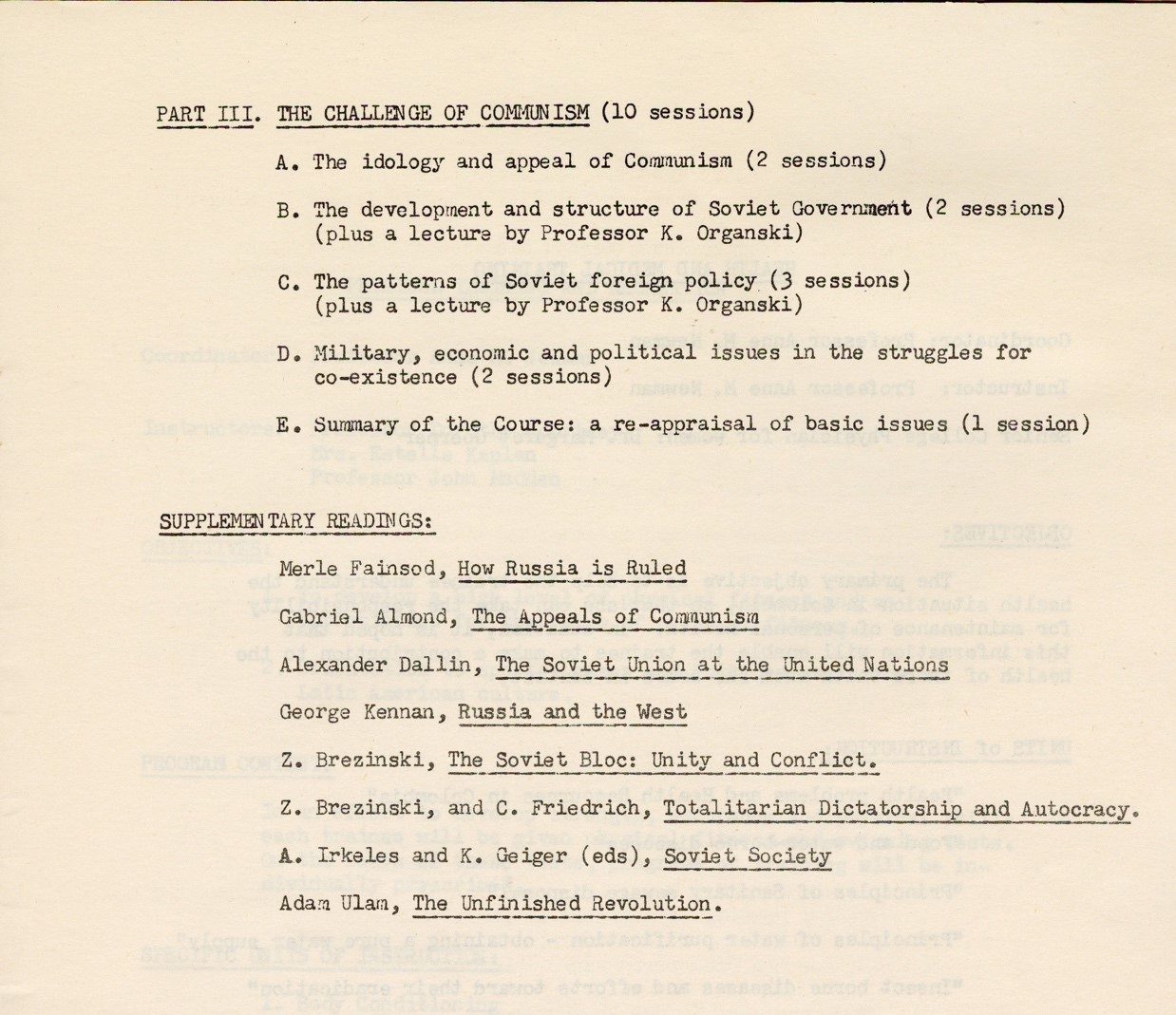

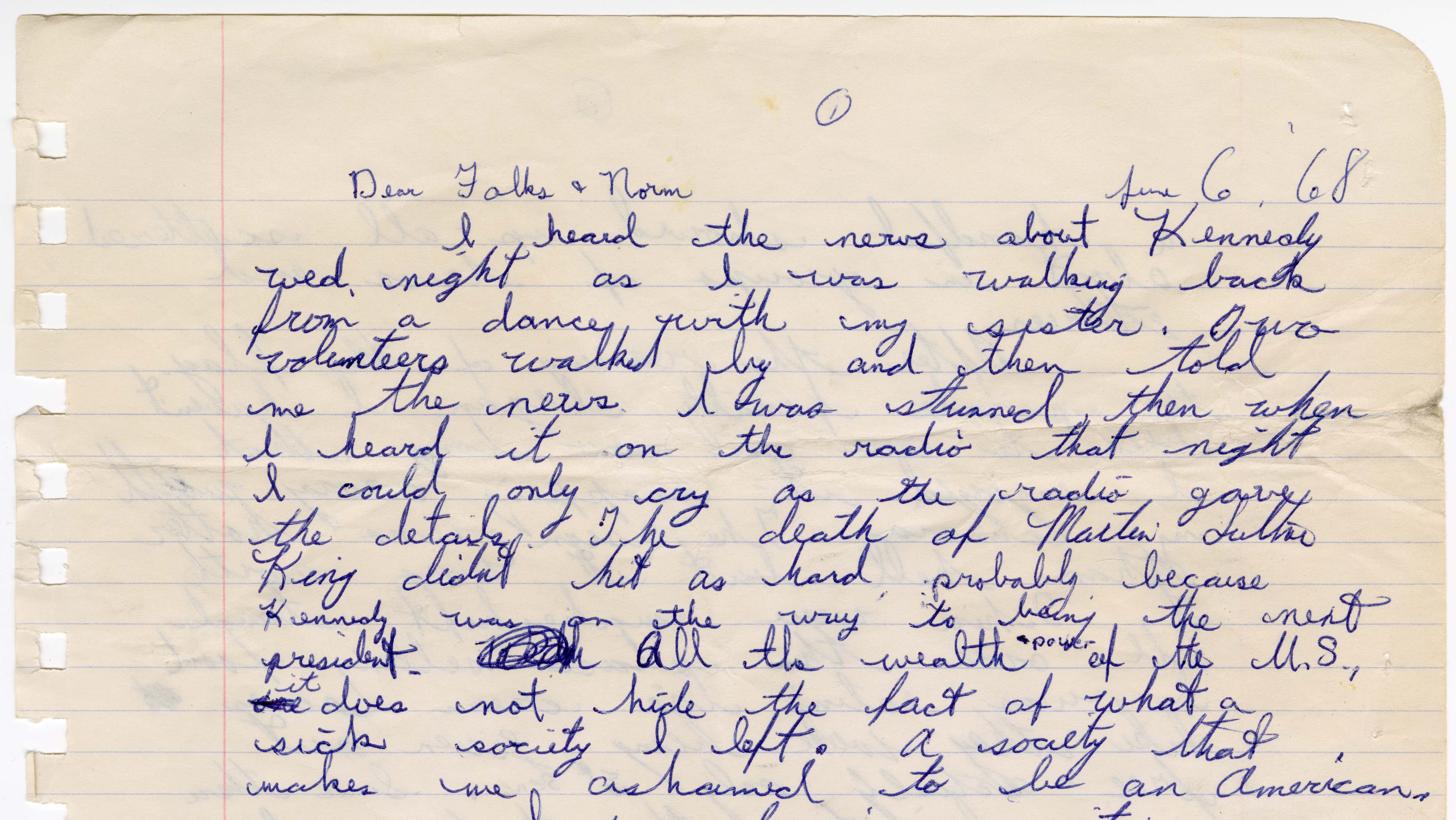

Even as he served in Western Samoa, Arthur Aaronson wrote home often about the 1968 Democratic candidates Senator Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy. He heard about the attack on Senator Kennedy from other PCVs and the radio, which gave details about what happened in the hotel kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel. Aaronson wrote to his parents that evening:

I heard the news about Kennedy Wed. night as I was walking back from a dance with my sister. Two volunteers walked by and they told me the news. I was stunned. Then when I heard it on the radio that night I could only cry as the radio gave the details. The death of Martin Luther King didn’t hit as hard. Probably because Kennedy was on the way to being the next President. All the wealth and power of the U.S., it does not hide the fact of what a sick society I left.

Aaronson’s letter home on June 6, 1968. Peace Corps Community Archives.

“I can only hope something good comes of all this.” Rodney King Riots- April 29, 1992

Photograph submitted by Dark Sevier on January 1, 2008. Flickr Creative Commons

In March 1991, a bystander recorded a video of four L.A. police officers beating Rodney King—a black motorist—for a reported 15 minutes as other LAPD officers looked on. Despite the video evidence, the court found the four officers “not guilty” of excessive use of force on April 29, 1992. Fueled by this acquittal and years of racial and economic inequality, riots broke out around South Los Angeles, raging for 5 days.[1]

Tina Singleton watched the riots transpire as she completed her volunteer staging in Cameroon. She had lived and worked in San Francisco for 10 years before joining the Peace Corps in 1992. Singleton followed the events and devoted several diary entries to her thoughts:

30 Avril 1992

Just heard about the 4 police officers in the Rodney King Case being acquitted—I was sad and in shock. I just don’t understand how the jury came to that conclusion—it blows me away—I’m so upset. It’s hard to concentrate on anything. I’ve had a few good cries. Also heard about the rioting in L.A.—it’s awful—but I understand the reaction. This was such a blatant disregard for justice and Rodney King’s civil rights—what a disgrace—and with all the evidence—a videotape and all the tapes of the officers’ conversations—and they still got off. Rose-Marie and Soyeon and I were/are very shaken by this. The U.S. is getting worse by the minute. It makes me not want to even go back to the U.S.—I’m happy I’m here for two yrs.

1 Mai 1992

It’s gotten worse—protesters are now in San Francisco, Atlanta, Dallas—they’ve blocked the Bay Bridge again. Can’t believe all this is happening—1992 and we’re having race riots. I can only hope something good comes of all this—the rioting, the looting—I almost wish I could pick up a phone and call Jean and Peggy. This was my first taste of what it’s going to be like when a serious situation arises in the U.S.—I felt pretty cut off. I see what volunteers mean when they say the shortwave will become your best friend. We listened to is as much as possible. What I wouldn’t do for a newspaper right now. This is the weekend we stay with a Cameroonian family—should be interesting. Though I’ve been upset and crying today about this Rodney King episode. I just can’t believe this has happened—It still blows my mind.

Lundi, 3 Mai 1992

Heard on the news this morning about L.A.—2,000 people hurt, 40 dead, Bush has declared L.A. a disaster area. I guess he’s going to LA this week to see the damage—don’t have figures on the other sites—saw the news this weekend on TV at my family. L.A. looks pretty bad—fires everywhere. Saw Rodney King—he was so upset. I felt so bad for him. He kept saying “it’s not right, this isn’t right—we only want our day in court.” He was pretty devastated about all the violence as well—he spoke about the people not being able to go home to their families. He looked so devastated—I felt so bad for him. He just looked so bad—so down. Like I said before—I hope something good comes of this.

5 May 1992

Well, last nite was a real shit nite. Sebastian brought newspapers from Dovala—A USA Today and some French language papers. I was not ready for what I saw—the pictures really floored me. I knew it was bad in LA, but I didn’t know how bad. The man [Reginald Denny] being dragged from his truck and shot—then robbed. The white man who was on the ground and being kicked by 3 Black men—it’s so sick. I’ve got such a bad headache. I can’t stop thinking about all this madness. This whole thing has me wondering why I’m here and not at home doing something to help the situation there.

It’s so hard to concentrate on my French—we’re here for only 2 more weeks. I am worried about my French—it doesn’t seem so important anymore. I hope I’m not going to feel like this for a long time—I know if I do, I’d leave, and I don’t think that’s what I want. I’m just so confused now. People here seem to think things will be better after this, but I don’t think so. I’m feeling pretty pessimistic at this point—I’ve no other reason to feel otherwise. Soyeon and I had a good cry last nite. We’re both in a daze, as is Rose-Marie. Heard on the news this A.M. that 10,000 businesses were lost as well as at least that many jobs—which is something we can’t afford to lose.

Soyeon and I are calling home tomorrow—I can’t wait. I really need to talk to the folks—I might call Jean too. I’m not sure—it will be great to at least talk to Mom and Dad. It’s sounds like Mom’s feeling a little lost with me gone. It’s weird for me not to be able to pick up the phone. I was dying to talk to them last night—tomorrow will come soon enough.

— T

As a Black woman who lived in California—or rather, anywhere in the United States—Singleton was shocked and devastated by reoccurring injustices in the United States. Cut off from her friends and family and relying only on news from the radio and infrequent newspapers, she found support from two other Black volunteers—Soyeon and Rose-Marie—to process the injustice of the trial and the impact of the riots.

Despite her initial desire to return home, Singleton spent 3 years in Benin, West Africa as a Health Educator. She became an international development worker for over 20 years and launched a program called Transformation Table, devoted to promote sharing a meal and culture between communities, in November 2016 in Charleston, SC.

“We shortly came to the realization that life had changed.” September 11, 2001

Living in a remote village in Zambia, Lara Weber was listening the the Voices of America when the voice over the radio reported, “”A… plane… has… hit… the… World… Trade… Center… in… New… York… City…” With no electricity, internet, or phone within a day’s drive, Weber explained feeling detached as more and more reports rolled in. She also worried about her father, who occasionally visited the Pentagon on business.

The weeks that followed were strange in that I had no Americans to talk with at all. Some of the elder men of the village visited me one day. They wanted to understand the news better, and their questions were interesting. One man wanted to know more about the Twin Towers and Manhattan. Why did so many people need to live and work on top of one another in such vertical spaces — had we run out of land in the rest of America? I tried to answer, but what I said felt inadequate and the whole idea of New York suddenly made no sense. Why did we pile into cities like that?

Rhett Power’s experience was a little different. As a volunteer in Uzbekistan, Power remembers a sense of confusion and urgency following the events, as the Peace Corps determined when to evacuate PCVs in the countries close to Afghanistan.

Power remembers sitting on the floor of a hotel room in the capital with his wife and a group of PCVs after a series of new volunteer training sessions. They were watching CNN when it happened. Power recalls the initial reaction:

I remember it distinctly. My wife and I were…Well, we were in the capital. So we were actually getting ready to go to the airport. I think a group had either come the night before or the day of. We were at a hotel. We were doing a Peace Corps training for new volunteers. There was another married couple there, they were education volunteers—I think he was a health volunteer—but anyway, we were together in the hotel. We were actually loving life because we were in a bed. A really good bed and we actually had two boxes of pizza on the floor. I think we had Orange Fanta and we were beside ourselves. The luxury of it all.

I distinctly remember this—we had a tiny little TV on CNN. You know, again we were watching TV. We didn’t have anything else to watch. But we had one international channel. And, that’s when it happened. And, we were watching it and just—we were just as shocked as everybody else was. I think [we] shortly came to the realization that life had changed. Because we all knew what would happen. Very shortly thereafter—within that hour we knew that something had changed and that something would change.

After three weeks, the Peace Corps evacuated Power and the other PCVs living in the Middle East and sent them back to the United States without reassignment.

As people back home find support within their communities, during times of tragedy PCVs find themselves relying on other Americans, throwing themselves into their work, or talking with their host communities about the implications of the event. Often, these tragedies lead to a renewed sense of faith in the mission of the Peace Corps—as seen in the uptick of Peace Corps applications in the wake of the Kennedy assassinations and 9/11. In other cases, such as the riots in L.A., it can be a reminder of how far we haven’t come.