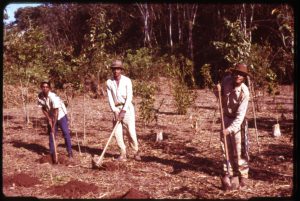

When people volunteer for the Peace Corps, they understand their role as a conduit of development and a representative of a developed nation. The often-overlooked factor is what they might learn from their host country. The four volunteers whose collections inform this article experienced regime changes in their host country, but what are more present are the changes within themselves. The collections show a process of: preliminary research about their host country, attempts to bring their old home to their new country, attempts to bring their host country to their old home, full and celebratory acceptance of the new culture, and finally they leave with a desire for greater understandings of global perspectives. Peace Corps Volunteers (PCVs) become global citizens through this process.

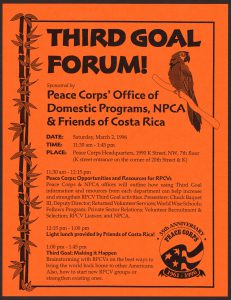

Preliminary research done by a PCV comes from materials published by the Peace Corps[1] and their host country.[2] The Peace Corps publications emphasized the variety of jobs performed by the PCVs along with the work ethic and values of the American people that would aid other nations.[3] Yet this was not the singular characteristic of the Peace Corps mission. A brochure of Debby Prigal’s (Ghana, 1981-83) emphasizes the mutualist nature of the Peace Corps experience, “Ghanaians are wide awake and have a lot to offer you for your personal development. Their only problem is that there is a shortage of manpower in vital areas of their economy. That’s where you fit in.”[4]

Peace Corps publications were useful in understanding the Peace Corps mission, but Gail Wadsworth (Uganda, 1970-72) also consulted Ugandan brochures and postcards to understand her host country better. These brochures advertise Uganda for foreign tourists and emphasize luxury hotels,[5] safari and the natural wonders of Uganda,[6] local coffee,[7] and crafts.[8] To prove Uganda’s appeal to Westerners, many brochures quote Winston Churchill’s My African Journey, 1908,

Uganda is a fairy-tale. You climb up a railway instead of a beanstalk and at the top there is a wonderful new world. The scenery is different, the vegetation is different, the climate is different and, most of all, the people are different from anything elsewhere to be seen in the whole range of Africa.[9]

All such curated representations did not fully represent what one would experience as a PCV.

In early months of service, PCVs tried to find ways to bridge the gap between American culture and the culture of their new home. Wadsworth wrote home unsure of her ability to relate to individuals whose experience was so far outside of her own. In one letter, she asked for help bringing American culture to Uganda:

I’ve asked mother, but perhaps you & the kids could also help. I would like pictures (magazine, etc.) of ANYTHING. When one girl told me that a beaver was a bird, I realized how crucial visual aids are going to be. How do you tell someone about the sea or steak when they’ve lived their entire life in a mud hut and eaten bananas 3 times a day? Also, I’ll teach units in advertising so any examples of that would be appreciated…Any with black people would be especially nice. Thanks![10]

This request shows both a readiness to make American cultural context readily available and accessible to the Ugandan students as well as a resistance to teaching the English language within the Ugandan cultural context. A month later, Wadsworth had begun to shed the notion that she needed to teach American culture along with English language. On 8 August 1970, she signs off a letter, “Take care; take a ride on the next Tilt-a-Wheel that comes round for me. (I couldn’t imagine describing that to a Ugandan!) Love, Gail.”[11]

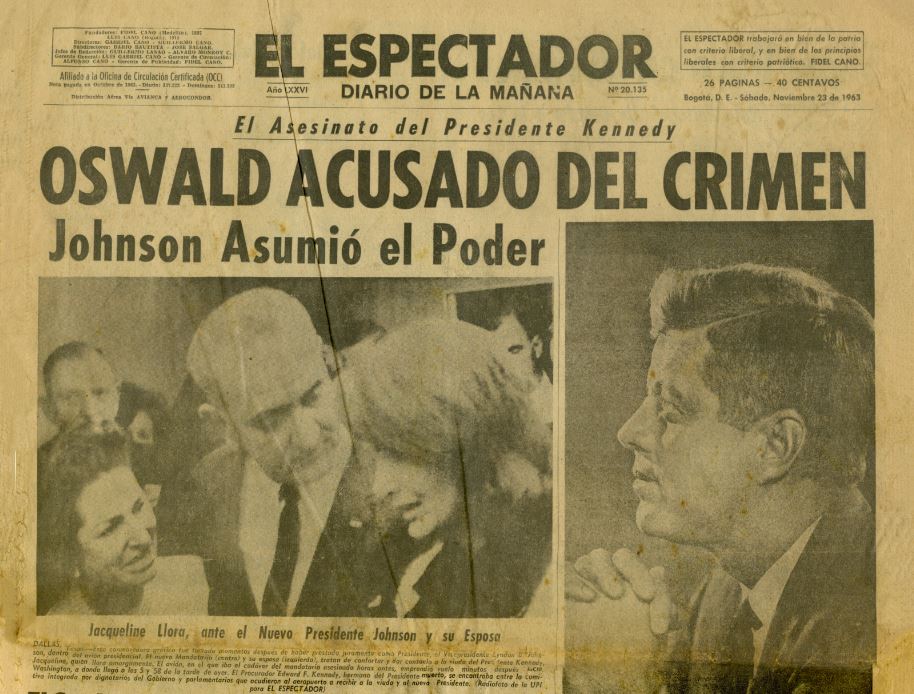

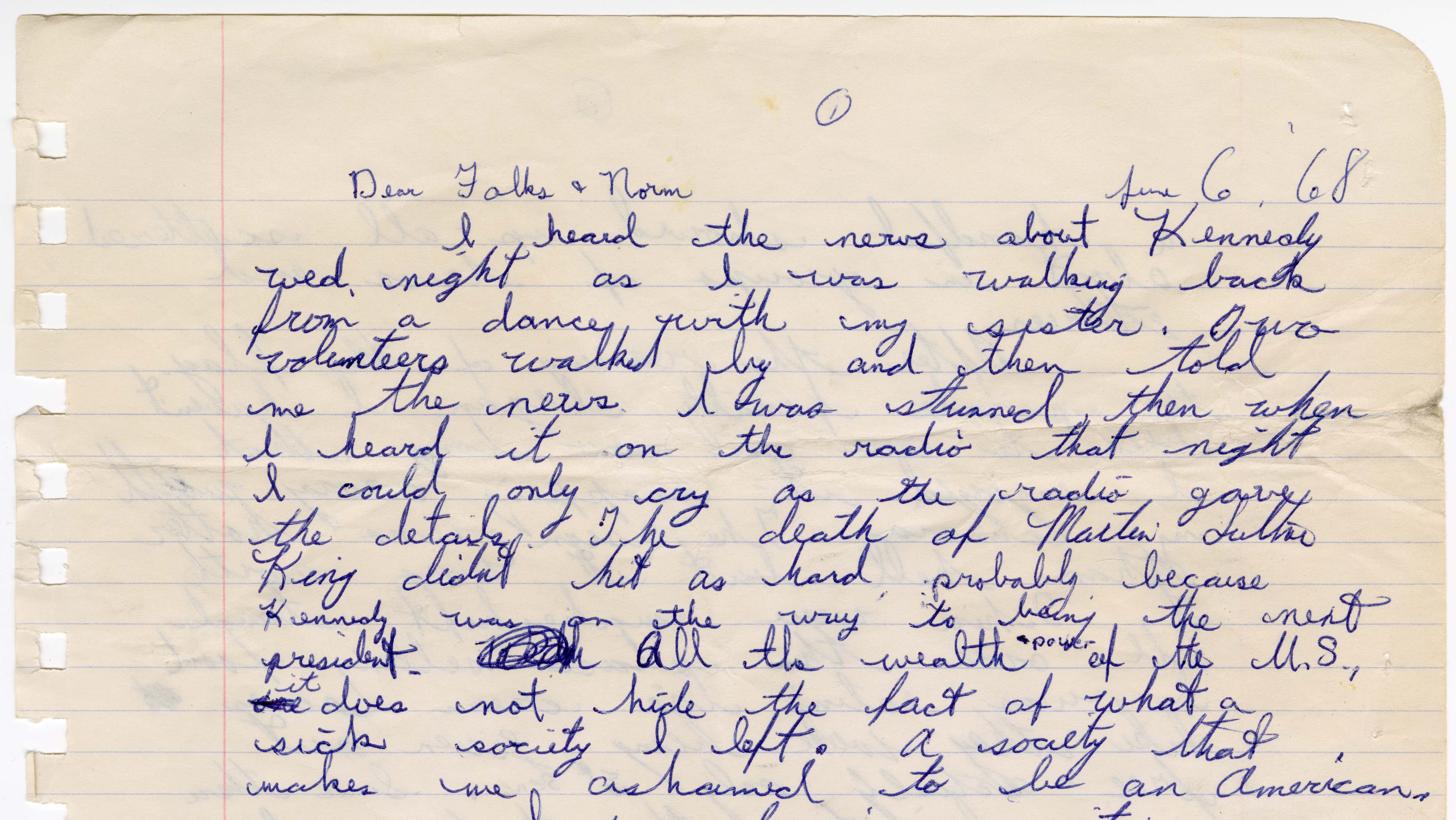

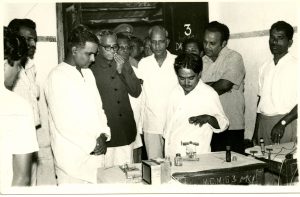

Eventually, PCVs experienced a reversal of this phenomenon as they realized that the people at home no longer shared their point of view. Volunteers responded in different ways. Wadsworth wrote, “It is difficult to convey much if anything about a country in writing. If I had only stayed here for 3 weeks I could write reams, but after 3 years I shall probably be able to say almost nothing.”[12] Ann Hofer Holmquist (Nigeria, 1966-68) found a solution and began to send soundscapes home over reel-to-reel recordings so her family could hear her new home.[13] She supplemented these with photographs, though not many. Things like the Niger desert, she explained, had to be experienced rather than seen in a photograph.[14] Geer Wilcox (Dominican Republic, 1963-65) had a similar experience with political ideologies. Through his stay, he warmed to the idea of communism, something that would be difficult to explain to Americans back home and something he decided to explore further in his own travels to Cuba.[15]

This shift in perspective was a part of a larger phenomenon of integrating with the host culture. One of Wadsworth’s last letters included a beautiful and affirming description of coming-of-age ceremony that she had attended.[16] [17] Prigal also grew to appreciate and embrace local culture. She wrote home, “One of my students’ mother, who is also my seamstress, was made Queen Mother of her hometown and they invited me. I had a great time. There was dancing, drumming…”[18] Holmquist made similarly open-minded observations towards the end of her service about the nature of honesty in different countries. Nigerian willingness to trust others and the consistency with which they lived up to that trust pleasantly surprised her.[19] She said that if she dropped money in the market, it was likely that someone would hand it back to her, rather than pocket it.[20] If one merchant could not make change for her, he allowed her to carry her groceries as she finished her shopping because he trusted her to come back with the right amount.[21] So, she figured, if they charged her twice as much because she did not know to bargain, that was fair, too.[22] These accounts show an appreciation for the other culture and the other ways of understanding that were different from American, yet just as legitimate and important.

The greatest development seen in these collections are the personal journeys as the PCVs underwent the process of becoming global citizens. Their day-to-day lives changed incrementally, but, by the end of their service, they learned the value of experiencing and internalizing another culture. By the end of Wilcox’s stay in the Dominican Republic, he had begun to question the role of American anti-communist propaganda and planned to travel to Cuba to learn more about its people and culture.[23] Holmquist showed, during a debate regarding the validity of warfare, an immense interest in foreign perspectives.[24] Like Wilcox, Prigal’s post-PCV plans involved travel; her closing remarks were, “Well, this is it! I’m leaving for London tomorrow…My plans are to see Julia and others and then travel, perhaps to Greece.”[25] This process of becoming more globally minded began with letting go of certain aspects of American culture and accepting the logics and customs of their hosts. Curiosity and the desire to continue to learn other cultures calcified this personal journey.

[1] Sargent Shriver, The Peace Corps (Washington: Peace Corps) Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 1: Application Materials Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[2] Publicity Services Ltd. on behalf of Uganda Hotels Limited, UGANDA: Hotels Limited (England: Brown Knight & Truscott Ltd.) Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 2: Brochures & Postcards Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[3] Shriver, The Peace Corps.

[4] Peace Corps, Peace Corps in Ghana (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office) 1979. Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 2: Brochures & Postcards Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[5] Publicity Services Ltd. UGANDA.

[6] Uganda Hotels, Ltd., PARAA: Safari Lodge Murchison Falls National Park Uganda (Kampala: Uganda Hotels, Ltd.) Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 2: Brochures & Postcards Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[7] Publicity Services, Ltd., Uganda Coffee (England: Brown Knight & Truscott Ltd.) Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 2: Brochures & Postcards Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[8] Uganda Crafts, Uganda Crafts (Kampala: Uganda Crafts) Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 2: Brochures & Postcards Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[9] Publicity Services Ltd., UGANDA.

[10] Letter, Gail Wadsworth to Mrs. Leroy Allport, 13 July 1970, Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 4: Correspondence 1969-71 (1/2) Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[11] Letter, Gail Wadsworth to Mr. & Mrs. C. M. Wadsworth, 8 August 1970, Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 4: Correspondence 1969-71 (1/2) Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[12] Letter, Gail Wadsworth to Dr. Milton M. Shulman, December 1970, Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 4: Correspondence 1969-71 (1/2) Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[13] Audio recording, Hofer Holmquist, Peace Corps Community Archives: Hofer Holmquist, Box 1, Reel 9724, Side 1, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[14] Audio recording, Hofer Holmquist, Peace Corps Community Archives: Hofer Holmquist, Box 1, Reel 9727, Side 1, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[15] Audio recording, Geer Wilcox, Peace Corps Community Archives: Geer Wilcox, Box 1, 38b, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[16] Letter, Gail Wadsworth to Mr. & Mrs. C. M. Wadsworth, 19 August 1972, Peace Corps Community Archives: Gail Wadsworth, Box 1, Folder 5: Correspondence 1971-72 (2/2) Uganda 1970-72, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[17] This being an even numbered year, as I have told you before, the Bagishu tribe of the Mbale area are having circumcision of boys, and yesterday I went to a circumcision ceremony…For two nights before, the boys wouldn’t have slept, but would have been dancing and running. They, as well as anyone else, is smeared over face and arms with millet flour and yeast paste. The boys have strings of beads around the neck and under each armpit, fur headpieces, cowrie shell belts, and bells on their legs. At the very place we were waiting two boys were to be done although several others would be at about the same time at various points along the mountain.

A few minutes before we arrived the boys and a huge group of people had been there after running up. Then they went off racing down the mountain as they had to go to a certain stream at the bottom to be smeared with mud. There are such a lot of people that destroy crops in running down but they don’t mind. They are not allowed to slip and fall down and they don’t. as I said it took us over an hour of climbing – well they raced down and up again through the mud in a matter of minutes. While we were waiting the circumciser showed us the ‘very sharp’ knife. What surprised me particularly was that the circumcisers are nervous and somewhat afraid. I was standing next to the man just before and he was very tense. One who was going to do some boys down was polishing the knife on some leaves and then suddenly leapt up with a shout and went racing down the hill to find them.

Anyway, they came racing back up and people began crowding into the makeshift area but the man in charge told us to come in and stood us right in front. The first boy came in, planted his feet firmly on the ground and clasped a short pole over his shoulders. He then has to stand looking straight ahead without showing any pain. The circumciser then steps in quickly, pulls the skin forward and cuts. When he has cut completely, eh holds the knife in the air and everyone shouts and someone throws handfuls of malwa (thick, yeasty millet beer) over their heads. Immediately after the cutting, some powder is rubbed on to curb the blood dropping down. The second boy was then done. After some minutes they are allowed to take off the beads and sit down. That is actually the end although the boys will be nursed and fed very well. For the next week or so they wear a cloth which is shorter than the knees wrapped round rather than any type of trousers (obviously).

[18] Letter, Debby Prigal to Mom & Dad, 20 July 1982, Peace Corps Community Archives: Debby Prigal, Box 1, Folder 7: Ghana 1981-1983 Letters to Debby’s Parents 9/17/81-5/15/83, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[19] Audio recording, Hofer Holmquist, Peace Corps Community Archives: Hofer Holmquist, Box 1, Reel 9726, Side 1, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Audio recording, Geer Wilcox, 38b.

[24] Audio recording, Geer Wilcox, 38b.

[25] Letter, Debby Prigal to Mom & Dad, 22 June 1983, Peace Corps Community Archives: Debby Prigal, Box 1, Folder 7: Ghana 1981-1983 Letters to Debby’s Parents 9/17/81-5/15/83, American University Archives and Special Collections, American University Library.